By Julia López-Robertson, Deanna Futrell & Shirley Geiger, University of South Carolina

In class we talk a lot about helping our students take a more global view of society; we want them to see beyond the borders of our city, state, and finally our country. One way that we can begin this process is by exposing them to quality children’s and young adult literature representing a variety of viewpoints, cultures, and people and then inviting them to examine and discuss these books. How can sharing children’s books (specifically about the Day of the Dead) help in raising awareness and developing an understanding of a culture different than one’s own?

In class we talk a lot about helping our students take a more global view of society; we want them to see beyond the borders of our city, state, and finally our country. One way that we can begin this process is by exposing them to quality children’s and young adult literature representing a variety of viewpoints, cultures, and people and then inviting them to examine and discuss these books. How can sharing children’s books (specifically about the Day of the Dead) help in raising awareness and developing an understanding of a culture different than one’s own?

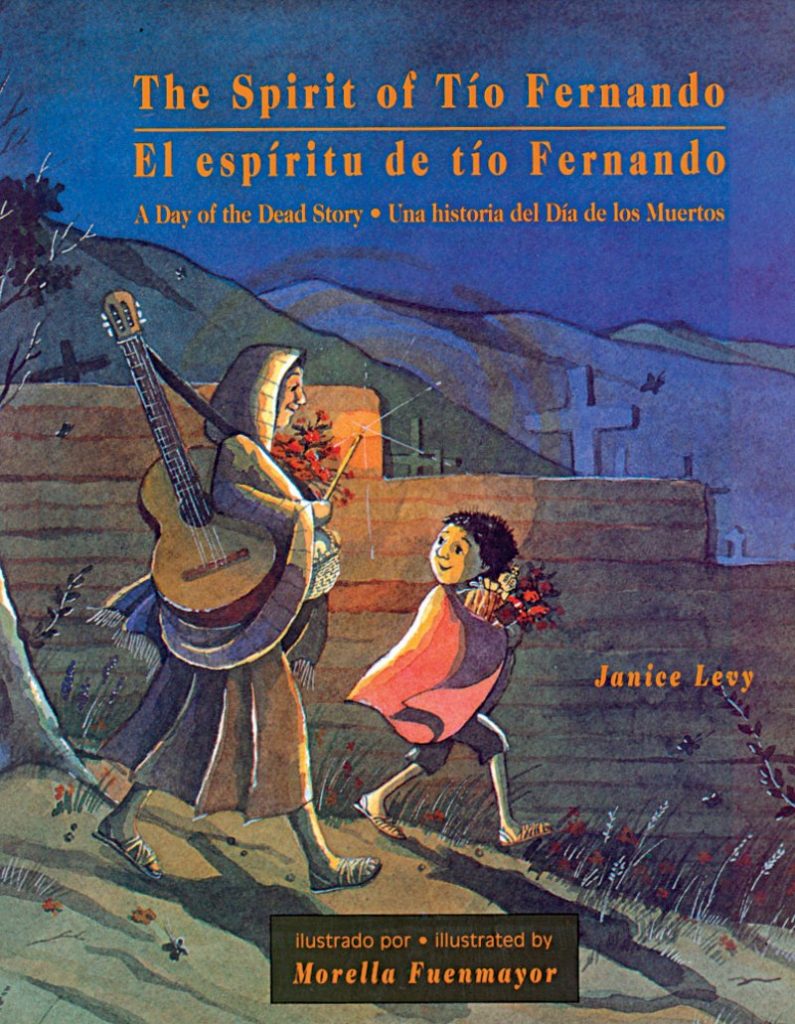

Janet Levy’s The Spirit of Tío Fernando offers a realistic portrait of the Day of the Dead, a 3000-year-old holiday that is celebrated in Mexico, Central America, Latin America, and in some areas of the United States. As an introduction to the story, Levy gives a brief overview of the Day of the Dead. She explains the origin and importance of the holiday as well as some of the typical activities and events that take place over the three-day celebration. By doing this, she provides the audience with some perspective on the historical connections as well as the spiritual context of the story. The fictitious story is narrated by Nando, a young boy living with his mother in a Mexican village, who tells a poignant story of love, loss, remembering, family, community, and tradition as he comes to terms with the death of his beloved Uncle Fernando six months prior.

Nando and his mother begin their celebration with an altar in their home on which Nando and his mother place his Uncle’s favorite foods and his wooden flute. When his mother sends him to the market to buy some things that remind him of his uncle, Nando buys traditional items for the Day of the Dead– candy, cakes, and trinkets. At the cemetery, Nando and his mother paint the tombstone and buy yellow marigolds, “the special flowers of the dead” to cover the top of his uncle’s grave.

Although there are only Nando and his mother in their household, they are part of a community whose adult members show love and concern for Nando. When he is not sure that he will meet his Uncle Tío’s spirit, his mother tells him “Some things we just know when it is time to know.” While he is shopping at the market, community members assure Nando that when Uncle Tío’s spirit comes, his “heart will be full” and that he will “feel good inside.” As darkness comes, Nando’s mother lights a candle and invites the soul of Tío Fernando “to join in the fiesta, to remember the world he left behind.” Sitting quietly beside the grave, Nando says he feels a “tickling across my cheek.” We are not told that Tío Fernando’s spirit comes back; it seems enough that Nando believes and “feels good inside.”

The illustrations by Venezuelan artist Morella Fuenmayor allow readers to enter the simple cottage shared by Nando and his mother, and where Nando’s clothes hang on the fence to dry in the Mexican sun. When Nando is sad, the images are dark and brooding; when he is happy, the scenes are filled with light. Readers see the beauty of the surrounding mountains, the fields, the clear night sky, and the vibrant and colorful village marketplace alive with the artifacts of the Day of the Dead celebration. The artist captures the community: Catholic nuns in their habits, a blind man, tourists with cameras, and vendors. We see what Nando says: “The street is crowded with musicians. People in costumes and masks twirl in circles. I dance to a mummer’s serenade and laugh at the actors on stage singing songs about life and death.”

What does this mean for teachers?

As Campano (2007) explained, “Some of my most profound teaching moments occurred when our classroom literacy engagements became informed by the students’ own experiences and identities. By finding a variety of ways in which to share their ethnic and migrant narratives, students participated in their own instruction and educational development (p. 41).” As we read Nando’s story in The Spirit of Tío Fernando and experienced the memories of his Tío Fernando, we were able to learn so much about how this holiday is celebrated. We were given the true meaning behind the figures and symbols that are traditionally used for this holiday, specifically those that might carry different, negative connotations in American culture. Some of the figures and symbols used, like skeletons and ghosts, might be negatively associated with Halloween since they are celebrated at the same time. By using this book as a way to share an immigrant student’s culture, and compare it to American culture, we as teachers can learn more about what each student brings with them to the classroom.

Selected Student Responses

Deanna

As we become more familiar with what is going on in the lives of our students we are better equipped to make connections with our immigrant students and possibly enhance the relationships between them and their fellow classmates. In Medd and Whitmore’s article (2001) they write, “As the children discovered new concepts about the people and places represented in their classroom community, they grew as communicators and knowledge seekers. Plus, the authentic reasons and audiences for talking in a second language made learning flourish (p.213).” Books like “The Spirit of Tío Fernando” help us learn about other cultures as well as give us an opportunity to share our knowledge with our non-immigrant students and colleagues.

What I liked most about this book was that it was from the perspective of Nando. Although he asked repeatedly to everyone he encountered throughout the day, “How will I meet Tío Fernando’s spirit?” no one could give him an answer, he had to experience it on his own. I think that this book is an excellent way to discuss differences in spiritualism and relate it to various cultural celebrations. Everyone has their own way of acting out their own traditions and beliefs that relate to their family and culture, and Nando was able to explore on his own what this special day meant to him. This book gives us an opportunity to think about how he welcomes the idea of meeting his uncle’s spirit through this cultural celebration, which is something that might be a foreign concept to many Americans.

Shirley

The Spirit of Tío Fernando is also a book that teachers can share with students to acknowledge the cultural heritage of students of Mexican heritage and to learn more about the traditions of the Americas. Gay (2000) asserts that the teacher who does not access this kind of material is not teaching in a culturally responsive way. Choosing not to teach students about the culture of Latin America, Central America, and Mexico can signal of a lack of respect for the background, culture, and language of students with roots in these areas. An equally important reason to teach about the Day of the Dead is to educate all students about the global community to which they belong. The Spirit of Tío Fernando: A Day of the Dead Story offers an authentic place to start.

Closing thoughts

Reading and discussing books about diverse cultures and viewpoints is essential for children of all ages if we truly want to prepare our students for life in a global society. Drawing on our students lived experiences, family histories, and linguistic knowledge and making them an integral component of the curricula is the starting point. We invite readers to comment, what do you think about ways teachers can use literature to engage children/students in understandings of our global society.

References

Campano, G. (2007). Immigrant students and literacy: Reading, writing, and remembering. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Gay, G. (2000). Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Medd, S.K. & Whitmore, K. F. (2001). What’s in YOUR backpack? Exchanging Funds of Language knowledge in an ESL Classroom. In P.G. Smith (Ed.), Talking classrooms: Shaping children’s learning through oral language instruction. International Reading Association.

Journey through Worlds of Words during our opening hours: Monday-Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m.

- Themes: Julia López-Robertson, The Spirit of Tío Fernando

- Descriptors: Books & Resources, Student Connections, WOW Currents