By Marie LeJeune and Tracy Smiles, Western Oregon University

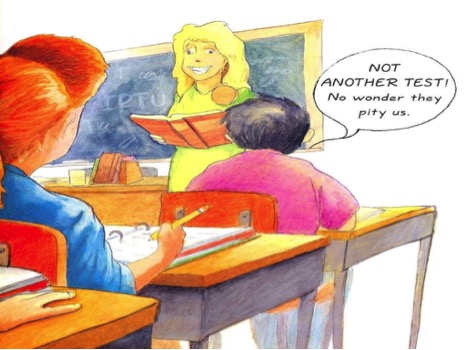

A boy in Miss Malarkey’s class makes the following observation,

A boy in Miss Malarkey’s class makes the following observation,

Miss Malarkey is a good teacher. Usually she’s really nice. But a couple of weeks ago she started acting a little weird. She started talking about THE TEST: The Instructional Performance Through Understanding test. I think Miss Malarkey said it was the “I.P.T.U.” test (Finchler, J, 2003).

Last week we talked about the personal toll testing has taken on our children and our decision to opt out because of the test’s impact. However, our reasons for opting out extend far beyond our concerns for our own children as we see the tests as part of a much larger problem in education; for this week’s post we examine the destructive effects high stakes have on teachers’ instruction and the conflicting messages such tests portray about teachers and schools.

Marie reflects:

“True confession—I was a kid who liked standardized tests. I liked filling in bubbles and reading passages and having scratch paper I doodled on after the test was over. Ironically, after a decade of taking standardized tests throughout my public school years, I do not remember a single result of those tests. My Mom saved a few printouts that arrived in the mail or she was given at parent-teacher conferences; evidence of my ‘aptitude’ as measured by those scantron bubbles. These tests were standardized, but weren’t high stakes the way tests are now. I didn’t think much about these tests really until I became a public school teacher. And in another true confession, the first few years I taught I didn’t think much about these tests either; once or twice a year we gave the tests, I read from a booklet of instructions, and while kids bubbled away furiously, I caught up on grading as I ‘proctored’ their exams.

It was when I moved to Nevada in the late 1990s that I experienced how the tests kids took were tied to high stakes—in this case, graduation. We no longer proctored exams to our own students, but to build in ‘reliability’ and ‘safe guards,’ we tested students in alphabetical groups by last name. The test booklets and materials were guarded with a security and protocol surpassing current airport screening, and everyone in the building talked about how misplacing test materials would have dire consequences. I remember thinking, ‘If I’m this stressed, what do these kids feel like?’ And then one afternoon, it happened. I witnessed a kid break. When the time expired for the high school math test, a girl who hadn’t finished sobbed uncontrollably, an ugly cry with wracking heaves I still hear to this day as she was told to put down her pencil. She didn’t know if she would graduate, despite having passed all of her classes and earned all of her required credits. This test’s stakes were incredibly high for her—and for the rest of the students I taught. Now, almost 15 years later, I live in Oregon where most students take these state tests on computers and immediately get the results flashed on the screen. I am no longer a classroom teacher but a teacher educator and the teachers I work with talk about the tears, the crumpled faces, and the stomach aches that accompany these tests for so many of their students and the horrible feeling of seeing ‘does not meet’ flash on a computer screen. Teachers know better than anyone what testing looks like in U.S. schools and this week we share some of their words about what our current form of testing is doing to kids, to curriculum, to teachers’ freedom, and to the educational system as a whole.”

Marie’s experience is neither unique nor uncommon, and both Marie and Tracy have seen firsthand the detriment the hyper-focused accountability rhetoric that surrounds testing has had on the teachers we know. Teachers describe not only the damage to kids’ identities, but also the huge impact the tests have on curriculum and instruction. Not only is there increased pressure to ‘teach to the test,’ there is simply less time to teach, period: less time for choice reading and literature circles, less time for science and social studies (non tested subjects in many states), less time for inquiry, and less time with technology that is not directly tied to testing. We could tell many stories that teachers have shared with us, but this week we will share some direct quotes from teachers in the field who are right now anticipating testing season and its impacts on students, curriculum, and teaching.

Voices from the field:

I teach eighth grade English language arts in Eastern Oregon and although there are numerous things I could say about the Smarter Balanced Assessment (SBAC) and standardized testing, I’d actually like to talk about it strictly from a numbers perspective. I don’t do this to make my math colleagues happy—although I’m sure it would do that as well—but simply because it speaks volumes about what’s wrong. This is what it looks like at my school:

Total school days this year: 170 days

Total school days this year: 170 days

Number of days spent testing: 22 days

Math Performance Task: 5 days

Math Computer Adaptive: 5 days

ELA Performance Task: 5 days

ELA Computer Adaptive: 5 days

Science OAKS: 2 days

When you crunch the numbers that’s almost 13% of our school year spent taking high stakes standardized assessments. Assessment that don’t help inform my instruction. Assessments that don’t provide any meaningful feedback to students about their skills or abilities. Assessments that don’t allow parents to see their child’s progress. Frankly, assessments that are useless to the most important stakeholders in education—the kids, their parents, and the teachers. And that’s strictly the actual test taking. This doesn’t account for the time spent teaching students to take the test or the time that many students will need beyond the estimated days above. These estimates represent the time the “average” student will need—but I have many who aren’t “average” anymore. In fact, with the new Common Core standards, I’d say most of my students aren’t average. They are behind. In the case that one might argue that 13% of the school year isn’t that much, there is a great deal of research about absenteeism in the US right now. Students being absent is one of my greatest struggles as a teacher and I have done a lot of reading about it. According to most of the research, students are considered to have chronic absenteeism when they miss 10% or more of the school year. This is less than we spend taking the SBAC assessment. I find it interesting that we know the very negative and long-lasting effects of missing even just 10% of the school year, yet we are ok with dismissing that much and more of our school year to high stakes standardized assessments that tell us nothing. –Christina, 8th grade teacher

I have witnessed 3rd grade students in tears because they were afraid of how they would do on the tests. After the test and they received their scores, students would either be really proud for passing or really down on themselves because they did not pass and then they would have to redo the test. All the while only learning they are bad at taking tests and receiving more anxiety. The tests are putting too much pressure on children, at such a young age.” –Anna, elementary school teacher

There’s no less authentic way to assess a student’s ability than to place them in front of a standardized high stakes test. As a high school English teacher and Reading Specialist I have been forced by my district to have students complete a “district level performance task” to “prepare” students for the SBAC. All this has resulted in is adding an additional two weeks of on demand testing to my juniors’ already test-packed school year.

In addition to this, due to the fact that the SBAC is tied to graduation at the secondary level, I have a classroom full of anxious, stressed, and worried children, who have continually been sent the message that they aren’t good enough if they don’t pass a test. Explain to me how this is supposed to help me educate, prepare, and set my students up for success? We talk about building a classroom environment conducive to learning that allows students to feel safe: Common Core and SBAC have robbed my students and me of such a place. –High School Reading Specialist who asked to remain anonymous

High-stakes testing (HST) has a negative effect on every member of the school environment – from struggling students who feel punished for their low performance (which is often not indicative of their true abilities), to teachers who are judged on student scores which are not entirely and specifically within their control; from parents who receive conflicting messages about the degree and significance of their children’s progress and the teachers’ efficacy, to administrators who inadvertently encourage poor practice by their teachers in the name of “better data.” Even high-achieving students are harmed by HST, experiencing a narrowing of the curriculum that eliminates opportunities for creativity, depth and breadth of exploration and critical thinking practice; anxiety over the increased pressure for them to “save” the school or teacher with their impressive scores; loss of instructional time – what students have described as “losing a chance to do an actual learning activity;” and a loss of motivation for real learning and education. We are facing no single greater threat to true critical thinking and critical practice in public education than high-stakes testing, and the effects are devastating for the strongest students and teachers, while being nothing short of catastrophic for those who struggle and are left without so much as a life raft. –Katie Elliott, middle school teacher

High-stakes testing (HST) has a negative effect on every member of the school environment – from struggling students who feel punished for their low performance (which is often not indicative of their true abilities), to teachers who are judged on student scores which are not entirely and specifically within their control; from parents who receive conflicting messages about the degree and significance of their children’s progress and the teachers’ efficacy, to administrators who inadvertently encourage poor practice by their teachers in the name of “better data.” Even high-achieving students are harmed by HST, experiencing a narrowing of the curriculum that eliminates opportunities for creativity, depth and breadth of exploration and critical thinking practice; anxiety over the increased pressure for them to “save” the school or teacher with their impressive scores; loss of instructional time – what students have described as “losing a chance to do an actual learning activity;” and a loss of motivation for real learning and education. We are facing no single greater threat to true critical thinking and critical practice in public education than high-stakes testing, and the effects are devastating for the strongest students and teachers, while being nothing short of catastrophic for those who struggle and are left without so much as a life raft. –Katie Elliott, middle school teacher

We’ve heard a lot about the negative impacts SBAC has on valuable instructional time and the toll it is taking on students and teachers. At the administration level, SBAC is also proving to have negative impacts. Consequences of implementing this kind of assessment system drains school building resources. Not only is our school computer lab shutting down for three months, creating the loss of technology that many teachers rely on for student research projects and interventions, but support staff must be pulled from small groups to help administer testing. During the three months of SBAC our school will lose four full-time support staff members to help administer the test. This will take away from small group reading interventions. At the same time, we will be paying additional school funds to cover substitute cost for intervention groups that cannot be canceled. Looking ahead, many school administrators (me included) are creating full-time assessment coordinator positions in their budgets. Creating additional positions to support assessment demands, take away from positions that work directly with students. —Elementary school principal, asked to remain anonymous

I think it’s important that people know how much instructional time we lose for these tests- probably a month of time lost to multiple tests and preparing for the test where we must deviate from the curriculum. I also think people need to understand how developmentally inappropriate these tests are for kids and how we are not given the resources or time to prepare them; especially kids in poverty or with culturally diverse backgrounds that don’t have the opportunities to use and navigate computers, that don’t have typing skills or life experiences that expose them to the kinds of vocabulary and questions they are being asked.

No matter how much I tell my kids that I don’t care about the score and that all I want them to do is try their best, it still causes a tremendous amount of anxiety.

Teachers were told to expect an 80% failure rate on the SBAC this year… A colleague and I did the practice test problem for 5th grade math which required kids to point, click and drag items and also type several paragraphs of explanation. The problem itself could be solved in anywhere from 10-20 steps; it took us over an hour to solve the problem.

I am fearful that my class, 80% living in poverty, many dealing with serious issues like domestic violence, death, basic needs not being met, will not pass and that they will feel defeated and selfishly that this will reflect poorly on my teaching skills. I am honestly nervous that only 1 or 2 will pass this year.

I also think it’s important to know how much is expected of us and how little time we have to teach too many standards. We are required to teach a minimum of 90 minutes of math per day, 90 minutes of reading and writing, 30 minutes of ELD, plus library, PE, music and lunch. I once added up the minutes mandated and the minutes we actually have and we are left with 21 minutes per day to teach science, social studies or work on building relationships with our students. —M., 5th grade teacher

The impact on 3rd graders will be huge. First of all, this is their first time ever taking a computerized test of this magnitude. One that will require keyboarding and using the mouse to manipulate the drawing of lines and shapes; skills they have not learned. The passage that I read during the practice test was about a NASA astronaut. I wondered what type of prior knowledge any of my students would have when and if they were presented with these types of passages. This experience made me think of one of my students from last year. The students were taking a state mandated test. A student was quietly crying. I went over to inquire what was the matter. She said she couldn’t understand what she was reading. She felt like a failure. —Third grade teacher, asked to remain anonymous

This sampling of testimonials from teachers and administrators mirror the broader discourses around the toll high stakes testing is taking on teachers, curriculum and instruction, and worst of all–the children and youth public schools serve.

Next Steps

Our first two blog posts have focused on the problematic nature of high stakes testing and the impact these tests have on schools, but we also know not all is hopeless. We hope by sharing these testimonials other educators find solidarity in how they are feeling but we also know many are taking action, becoming collaborative activists for change.

For the next two blog posts we will be focusing on how teachers, parents, and administrators are pushing back against practices and policies that have led to the over-testing/hyper data driven accountability movement in hopes that readers will be as inspired by their actions as we are, and will find the courage to push back themselves. Additionally, we will be offering perspectives on how we think literacy learning should be assessed.

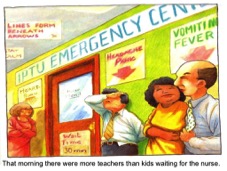

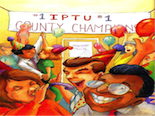

While Testing Miss Malarkey portrays a humorous look into the crazy effects testing has on everyone in the school’s community, the ending is disappointing in a way. The final image shows teachers and the principal having a party because their school was awarded for the high scores their students earned on the I.P.T.U. test. Then again, Miss Malarkey faced a different world in 2003 than teachers do now in 2015.

We would like to offer an alternative ending in light of tests such as the SBAC and PARCC.: same image, but with teachers and administrators throwing a party in celebration of the growth their students have demonstrated through locally generated assessments that highlight what children can do, and the important work teachers do every day in guiding the development of children and youth. This is the activist work we, and many of our teaching colleagues, are striving towards.

We would like to offer an alternative ending in light of tests such as the SBAC and PARCC.: same image, but with teachers and administrators throwing a party in celebration of the growth their students have demonstrated through locally generated assessments that highlight what children can do, and the important work teachers do every day in guiding the development of children and youth. This is the activist work we, and many of our teaching colleagues, are striving towards.

Journey through Worlds of Words during our open reading hours: Monday-Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit archival stream.

- Themes: Marie LeJeune, Tracy Smiles

- Descriptors: WOW Currents