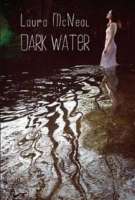

Dark Water

Written by Laura McNeal

Alfred Knopf Books, 2010, 285 pp.

ISBN: 970-0375849732

It wasn’t wrong in theory. It wasn’t forbidden. But I understood that it was very strange and different, someone like him and someone like me. The people who have nothing aren’t allowed to touch the people with cars and houses. They can work here. That’s all. (p. 171)

Fifteen-year-old Pearl is caught between two worlds. The world of her old life where she had everything she ever wanted and her new reality where she lives with her mother in the old guest house on her uncle’s avocado ranch. Her father has left her mother for another woman and as part of his new life has decided that it is time for Pearl’s mother to realize what it means to make a living. As a result, Pearl’s new existence is substandard while still on the periphery of the wealth she once knew. Pearl’s confusion and sense of imbalance is heightened when she comes to further realize that even her current situation is divided between those who come from wealth and those who do not. For, even as she and her mother are barely surviving on her mother’s wages as a substitute teacher and her own part-time work in town, Pearl is reminded that a relationship with one of the migrant workers is strictly taboo. Pearl, however, cannot stop thinking about Amiel, a young migrant worker who lives in a makeshift hut along the Agua Prieta Creek. She decides her friendship and budding romance with Amiel is worth pursuing, and thus she begins to meet with Amiel secretly while also attempting to understand the discrimination that is ever present in their relationship.

A National Book Award Finalist, Dark Water is a sensitive, gentle love story between a Mexican migrant worker and the niece of a wealthy landowner. Set in California when the 2007 wildfires ravaged the state, this novel is a contemplative and timely coming-of-age story that addresses the issues of class and ethnicity that reflect the current political climate of the West and Southwest United States. Dark Water is a story that adolescents will find easy to relate to as well as engaging. Amiel’s lack of voice will resonate with their oft-times silencing experienced by teens, as well as allow them to note its use as metaphor in the novel. The setting is crucial to the evolving plot, which young readers should be encouraged to address along with the climatic ending and sparse communication between Pearl and Amiel.

Within a unit on discrimination, border crossing, intercultural connections, or forbidden friendships, Dark Water would make a nice complement to books such as Esperanza Rising (Pam Muñoz Ryan, 2002), Seedfolks (Paul Fleischman, 2003), If You Come Softly (Jacqueline Woodson, 2000), or Summer of My German Soldier (Bette Greene, 1973). There is also La Línea (Ann Jaramillo, 2008), Illegal (Bettina Restrepo, 2011), and Grab Hands and Run (Frances Temple, 1995). Dark Water would make an interesting lead into Shakespeare’s Othello or Romeo and Juliet.

Dark Water contains themes about the price of loyalty, the loss of family and love, and the uncertainty of risk-taking during dangerous times. It will have readers struggling over the conflicts inherent in growing up, the questions of discrimination and family allegiance, and the consequences of actions made with the best of intentions. The ending is both satisfactory and ambiguous, but was foreshadowed throughout the novel.

When interviewed as part of the National Book Awards, McNeal noted the following in response to the subject matter of her novel:

For years and years, I’ve watched migrant workers ride their bicycles up steep hills to work in avocado groves, yards, or plant nurseries. I’ve seen them on our street going grove to grove, locked gate to locked gate, pushing the call buttons to ask, “Any work for me?” I’ve driven past the corners where they wait to be hired, hour after hour. I’ve seen how they swarm cars that pull over, and I have been inside one of those cars. About 14 years ago, I was led by a friend into a migrant camp that was completely invisible from a major street in Fallbrook, in a thick stand of trees 200 yards from a school. My friend told the men living there that I was a journalist who had come to help them. If they talked to me, he said in Spanish, their lives would get better. I have always felt this was a promise I didn’t keep; the article ran in a newspaper, but what did it change for them? I’m still trying to make good on my word.

She has also written other books for adolescents with her husband Tom, including The Decoding of Lana Morris (2010), Crushed (2007), and Zipped (2004), all of which deal with ethical and family issues. She spent much of her youth in Air Force towns in the West and Southwest and was a high school English teacher in Utah before pursuing writing full time. She currently lives in Southern California with her family. Dark Water is her first solo publication.

Holly Johnson, University of Cincinnati

WOW Review, Volume III, Issue 4 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/review/iii-4/

this is one of my favorites. great review, connected to reality very well.

This is a very unique book written about Maasai culture primarily from the perspective of a pre-adolescent female growing up in that world. A very engaging book in terms of background, cultural perspectives, and the surprising universalities of growing up, regardless of where in the world you are. The female protagonist, Namelok, will undoubtedly give new insight into what it means to be young in Africa to Western readers. This book is particularly enjoyable in terms of how it gives snapshots of what we have already seen about the Maasai culture, Kenya, wild African animals, etc. Yet at the same time, the viewpoint and perspectives of the people inside that culture take it a step further in terms of their modern struggles, survival, traditions, and what that means for the modern day Maasai. What I found particularly interesting are the explanations of how an African tribe views animals and their natural world, along with the ways in which they connect with it. Will that world be lost forever this century? It is a theme that shines through as a common thread running across the pages of this very original book written by a Westerner, Cristina Kessler, under the guidance of Kakuta Ole Maimai Hamisi, a Maasai who helped in the editing of the manuscript. This book stands out as another fine example of African literature, which is a literature that we know little of in North America, and that we undoubtedly need to get much closer to.

For your in formation “wunschkind child without a country” by Liesel Appel as paired in your review of “Traitor” was written by Mrs. Appel where she adapted her memoir “The Neighbor’s Son”for young adult readers. The site is wwwtheneighborsson.com.