Moving from topics to Conceptual Thinking through Literature Discussion: The Other Side

by Amy D. Edwards, Fifth Grade, Van Horne Elementary, Vignette 2 of 3

Teachers at our school work collaboratively with our Instructional Coach in a setting that we call the Learning Lab. Classes come to the lab once a week for a lesson and then work on connected areas of study in their regular classrooms. Our focus this year has been literature discussion and facilitating students’ thinking more deeply around conceptual issues rather than only discussing topics. Concepts enable us to think abstractly and to develop interpretations that lead to inquiries around issues instead just naming topics or ideas in texts (Santman, 2005).

In years past, I engaged my fifth grade students in book clubs that were teacher led, accompanied by a list of questions generated by me for students to answer. These book clubs encouraged surface-level thinking and getting the right answer. Only occasionally did students go deeper in their discussions to address issues in the text. I wanted to try discussions that were more student led and with a format that would encourage personal connections and conceptual thinking rather than talk about topics. This became my mission for the school year. Literature circles provide ways for students to employ critical thinking while reflecting, discussing, and responding to books. Noe and Johnson (1999) describe literature circles as guided by students, in small groups, responding in depth to what they have read. The heart of this approach is collaboration.

In an effort to encourage students to connect their thinking to difficult social issues in literature, we chose to look at the picture book The Other Side, by Jacqueline Woodson (2001), in lab. Our goal was to see the kinds of personal connections children would make and the questions and wonderings they would form, as well as how long kids could talk about one idea. I had no idea what impact this book would make on my students. It ended up being a touchstone book for many discussions throughout the year.

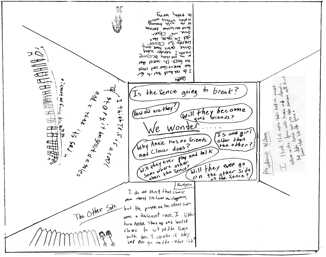

After listening to the story, students were asked to respond using quick writes, 3-4 minutes of uninterrupted writing and sketching, on consensus boards in order to support their thinking about their responses to the story. The quick writes were to help students reflect on individual connections and thinking about the book. They also allowed all of the students’ responses to be available on the table. There are always a few students who, for whatever reason, don’t respond out loud. They are either too shy or can’t push into the conversation successfully. With the quick writes on the consensus board, everyone’s thinking and response was on the table for all to see.

Consensus boards are created on large sheets of paper with a large square or circle in the middle and four sections surrounding it. The circle contains the title of the book or a key theme from the book. In the individual sections, each person writes or sketches personal connections to that theme or book. The group shares these individually and then comes to consensus on the tensions, issues or big ideas they want to explore further. These tensions are written in the middle of the board. In this case, small groups were asked to decide what they still wondered about the story as a group after sharing their connections.

In small groups students shared the ideas they had recorded in the quick writes. As I moved from group to group some of the questions being discussed were:

- Why the girl crossed the fence when her mom told her not to?

- The differences in how the mothers responded.

- Why weren’t they supposed to cross the fence?

- Why did they make the “stupid” fence in the first place?

- Why didn’t the mother scold the girls for sitting together?

These comments clearly represented a lack of understanding about race relations and historical attitudes and laws about segregation. Students seemed truly perplexed as to why the fence was there and why the girls were told not to cross it. Their lack of awareness about racial issues was probably a reflection of the lack of diversity in my classroom with 3/4ths of my students coming from white backgrounds and the rest from Latino, Filipino, Russian, and biracial families.

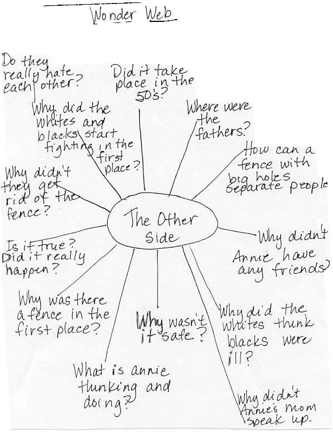

After students came to consensus on what they were still wondering, they recorded these in the center of the consensus board. They were then asked to come to the Story Floor and each group shared with the class. The wonderings were recorded onto a web.

As a whole group they wondered:

- When did the story take place?

- Is the story true? Did it really happen?

- Why didn’t they just get rid of the fence?

- How does a fence with big holes in it separate people?

- Why didn’t Annie have friends?

- Why wasn’t it safe to cross the fence?

- Why did the whites and blacks start fighting?

- Did they hate each other?

We wanted to see if students’ questions about this book would take their conversations deeper. We decided to continue with The Other Side for the next discussion in order for students to be able to choose a topic from their web to discuss in depth.

In the lab the following week, our focus was to engage students in sustained talk in small groups around a specific question or tension. A copy of the Wonder Web from the previous week was placed on each table. In small groups students were asked to come to consensus on which question they were most interested in exploring. They were then asked to come to the whole group to think about that question and to look for ideas that would help the discussion as the story was again read aloud to them.

After the re-reading, students returned to their small groups to do a quick write and then turn and talk. They were then invited back to the Story Floor to discuss what of significance came up in their discussions. Although each group was supposed to share, students became involved in an engaged discussion around their new understandings, connections, and tensions. Afterwards, two girls complained that not all of the groups got to share, but what took place was a real literature discussion. Students made connections, built on each other’s comments, and deepened their understanding of the big issues in the book.

In the whole group discussion, Brody’s group noticed that the fence really wouldn’t hold anybody. Brody thought the fence was “symbolic,” instead of physically stopping them. The fence pictured in the text was a wooden rail fence. Brody thought that the fence was meant to define divisions of property, stating, “For example: This is our side, this is yours.” He mentioned that it wouldn’t take much to knock down the fence, indicating that if you really didn’t want it there it could be removed easily.

Sydney said, “Yes, but if you did cross over the fence you would have to ‘pay the price.’” She meant that there would be a consequence. Conner felt that whites could go over but not blacks without a consequence. He believed that it was blacks who were being discriminated against. Andrew said that this was not fair. There was a bit of outrage in his voice—fairness is very important to fifth graders.

Conner wondered who owned the fence. Someone else suggested that maybe the government owned it. Evan said that maybe someone else owns the fence and made the rule that you can’t go on the other side. Maddy argued that they really didn’t want to keep people out and that they couldn’t stop them. The fence didn’t look that imposing to her.

In the text, the mother tells Clover that it isn’t safe to cross the fence. Students wondered why it wasn’t safe. The topic of forced integration came up but children didn’t use those words. Instead they referred to a time when children were escorted to school because some whites hurt blacks, referring to Ruby Bridges and her safety in attending an all white school. Most had seen the movie about this event at school the previous year. This connection led students to think that this book was set in the 1950’s during struggles around desegregation and civil rights.

One student wondered why there were no boys or fathers mentioned in the story. The students thought that maybe Clover’s father could have worked long hours. Another student asked, “Was he a slave?” Clearly students were confused about the chronology of African American history. Based on this comment, we decided to engage students in working on a timeline associated with African American history.

Racism was brought up as one student commented on the difference in the affluence of the two main characters and the opportunities available to them because of their skin color. They noticed the way the girls were dressed and the differences in their houses. As the students looked closely at the book for clues, they noted that the girls were wearing dresses to play in and thought this signaled a different time period. It was really hard for me not to jump in and make corrections in their thinking, but I tried to stay out of the conversation so they could talk this through on their own.

The students moved from these comments about race and historical context back to the idea that the fence was meant as a symbol or warning. They said that literal fences have barbed wire at the top, like for jails and at the border. This fence had big holes in it so it really couldn’t keep people out. They were now sure that the fence was a symbol.

Several students raised the question about why this particular fence had been built and whom it was trying to separate. They made a connection to Martin Luther King Jr. and the Civil Rights conflict between blacks and whites. Several children thought that the fence was separating blacks and whites in that community to keep the conflict to a minimum. They believed that this fence was not “real” because it didn’t have barbed wire, but was meant to be symbolic or used as a warning. One student argued that if the people who made the fence had really not wanted to have anyone cross over, they would have made the fence electric. Instead this fence was easy to cross, but served as a warning that you would have to pay the price if you went to the other side.

Some of the students thought that white people put up the fence, and wondered why white people and black people fought in the first place. Andrew noted that the Irish didn’t fight with the Americans when they arrived in the U.S., saying, “Why did the blacks and whites fight? We were peaceful with the Irish.” Cassidy offered that maybe it was because we knew something bad had happened in their country, so we said they could come here. Natali said that some people just came here and said when they arrived, “I’m here, whether you like it or not.” She obviously felt they had the right to be in the U.S.

Christian said that Annie crossing the fence was like people crossing the ocean. “Whites brought blacks here as slaves, and saw them as ill, and this added on to a bigger fight,” he commented. “They weren’t ill but whites made up that they were because they didn’t like blacks.” I could tell that he was talking to work through his ideas. He wasn’t sure where he was going, but was struggling to work out his understandings as he talked.

Conner commented that the girls in the story could stop the fighting because Annie and Clover didn’t know about the past fights. Christian continued with his thinking out loud by saying that whites had no respect for slaves and it got worse when slaves were free. He thought that whites still treated blacks as slaves. Whites did not want them to have friendships or relationships with others. Conner wondered why Clover’s mom didn’t tell her why there was a problem and connect her to the broader world. He also wondered if the girls would be different from their moms when they grew up and tell their kids to become friends.

Ashleigh pointed out that the fence seemed longer because it made you want to go to the other side, but you weren’t supposed to. She made the analogy of knowing we can leave our room but if we were told we couldn’t, then we would see our room as small. She believed that the fence represented freedom through being able to cross the fence. “The fence was all about freedom. The fence was a trap because they couldn’t go over it – they felt trapped there. It separated them.”

Although we had planned for this whole group discussion to be a short sharing from each small group about their focused question, the students instead engaged in dialogue with each other about issues that were continuing to trouble them. Students asked and answered questions, made connections to the real world, and built on each other’s comments. Sometimes students were confused as to the facts about race relations and historical contexts but the one overriding big idea that kept coming up was the fence as a symbol for something that divides us. The emergence of this symbolic theme was exciting to me as a teacher. The kids were thinking deeply and in symbolic ways using figurative language to express what they were thinking. It was exciting to see this happening before our eyes and it was all the more important to us as a team to know that the kids were constructing their own meaning, not being “spoon fed” standards from an adopted curriculum.

In my classroom at that time, we were reading novels in literature circles with a focus on international children’s literature. We were reading Esperanza Rising (Ryan, 2000), Nory Ryan’s Song (Giff, 2000), In the Year of the Boar and Jackie Robinson (Lord, 1984), and A Single Shard (Park, 2001). The common thread in these books is a main character who faces a challenge or something that separates them from something they want. The students were at the point of discussing these books in their small groups and so I moved from group to group checking on the progress of each discussion. As I listened to the group discussing Esperanza Rising, Evan asked, “I wonder if there are any fences in this part of the story?” I stopped dead in my tracks and asked him to repeat the question so that everyone in the class could hear. He said it again and everyone immediately knew what he meant. They had learned from our discussions in the lab that a “fence” was a symbol for something that divides us. Students had found a frame to use in connecting texts. This was a conceptual leap I had never seen students make as a group. I was so excited that I couldn’t wait to tell our instructional coach and the rest of the team.

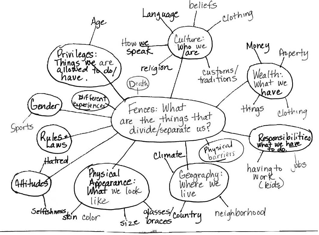

Each literature circle group went on to share the “fence” in their particular novel. These fences were shared with the class and used to create a web of the different ways in which people are separated. Conner noted, “If there’s a fence in each story, there must be a ‘bridge’ too.” I could not have been more pleased. They were stretching their thinking in new ways to make meaning between texts. This was a teacher’s dream. The kids were learning to think beyond topics (“these books are all about dogs”) and reaching to complex links between texts through connections to concepts and larger social issues.

Since the concept of fences had become such a significant frame for the students in thinking about what divides or separates people, we created a class web to pull together our ideas and understandings. This web showed me that their connections had gone beyond the book, The Other Side, in conceptually understanding fences as a broad frame for thinking about life and other texts. Their web represented far more complex ideas and served as a tool and point of reference for further explorations in many other projects we did later in the year.

During the rest of that school year, my students referred to “fences” as things that divide and “bridges” as things that bring people together. The Other Side provided the defining moment in our literature circles and changed the manner in which the students looked at literature for the rest of the year. This was what I was hoping to accomplish with transitioning from book club to literature circles. These groups were student-centered, focused on exploring the concepts that lived behind the words, not just identifying the topics within them.

References

Giff, P. R. (2000). Nory Ryan’s song. New York: Scholastic.

Lord, B. B. (1984). In the year of the boar and Jackie Robinson. New York: Harper & Row.

Noe, K. S. & Johnson, N. (1999). Getting started with literature circles. Norwood, MA: Christopher-Gordon.

Park, L. S. (2001). A single shard. New York: Yearling

Ryan, P. M. (2000). Esperanza rising. New York: Scholastic.

Santman, D. ( 2005). Shades of meaning. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Woodson, J. (2001). The other side. New York: Putnam’s.

WOW Stories, Volume I, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesi1/.