Exploring Family Perspectives of Latino Children’s Literature

By Jeanne G. Fain and Robin Horn

Second-grade bilingual students in Robin’s classroom engaged in family literature discussions by first selecting one book out of four possible choices every three weeks to share and read with their families at home. Students excitedly chose books in the language that resonated with their family — Spanish, English, or both languages. Through this kind of home/school collaboration, students find a comfortable place to experience the joy of reading with a relative or caregiver. Families open the book and see their culture represented across the pages. Rich literacy experiences are created in Spanish and/or English and knowledge of literacy is shared as families read and discuss the literature. To document family-led literature discussions in the home, students’ families used disposable cameras to capture these experiences and invite teachers to see the power of literature in their lives.

“Me parece una excelente oportunidad para establecer una relacion mas estrecha con el niño y intercambiar puntos de vista sobre un mismo tema,” states Mrs. H. [“It appears to me an excellent opportunity to establish a deep relationship with my child as we exchange our points of view around the same theme.”] The enthusiasm this parent expresses for reading and talking about high quality bilingual children’s books illustrates how family-led literature circles in the home provide children with rich opportunities to talk about a book in the language of their choice.

Robin, a second grade teacher in a predominantly Latino school, and Jeanne, a university professor, are actively engaged in thinking about how parents and their children talk about linguistically and culturally diverse literature within the home and the classroom. We meet regularly and discuss how we can use Latino literature with second grade students and how we can effectively create authentic partnerships with families. We begin this engagement with Latino children’s literature each year by holding a bilingual informational meeting about literature circles and welcoming second grade families to join us in reading and discussing literature throughout the school year. Families attend our meeting and we informally dialogue about how we can build connections with Latino literature in their homes and in the classroom. We invite thoughts and suggestions within our discussion and encourage parents to use their native languages as they work as a family to figure out thoughtful ways to talk about the literature in their homes.

Mrs. R., one of the parent participants, commented:

I think it’s a great opportunity to spend time together and share our ideas. I think that these books are wonderful. I get to see and hear her read in Spanish. She is learning to read in Spanish independently without instruction. When I was a child, I couldn’t do this kind of project with my parents because they didn’t understand English. These books are great for the students’ parents who don’t speak English.

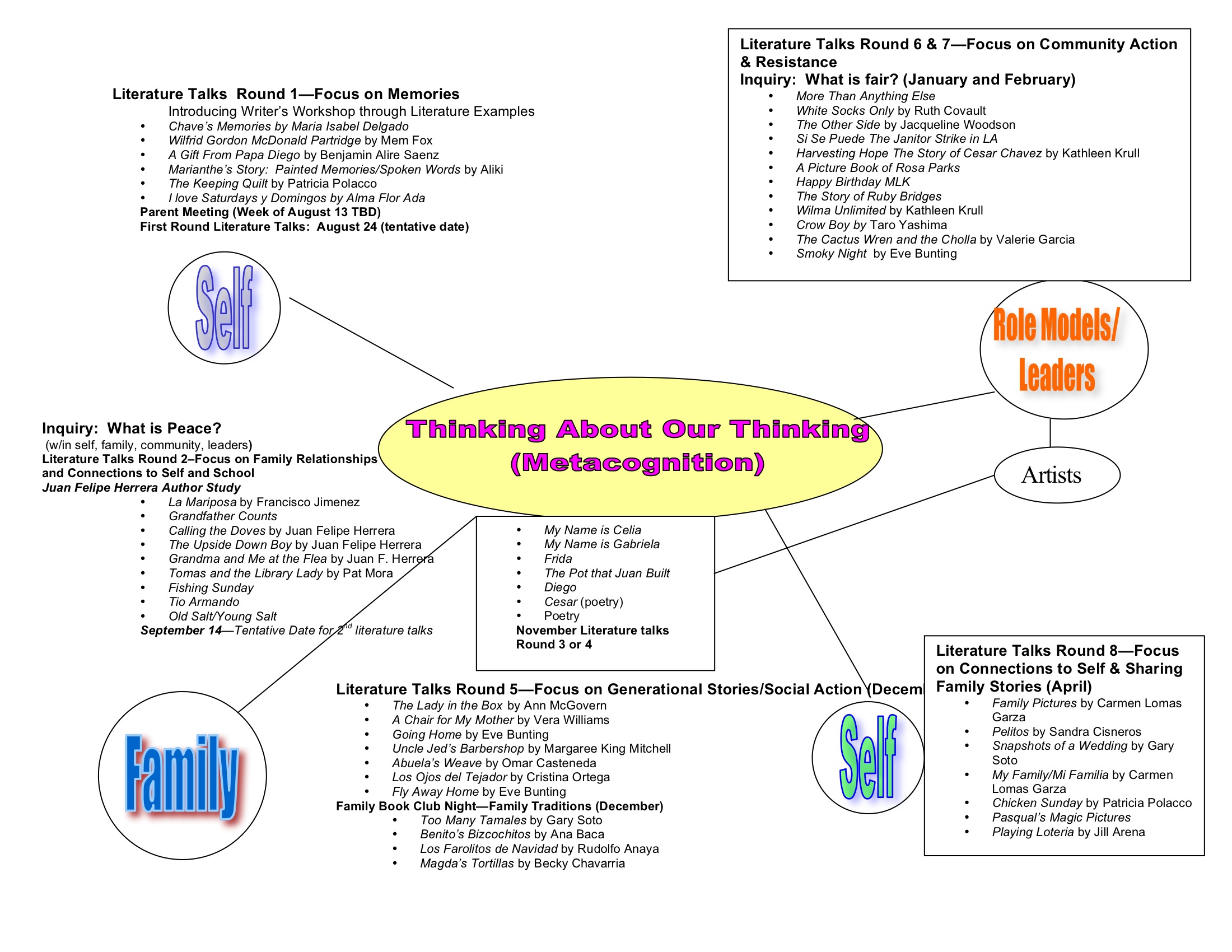

To engage students with Latino literature, we purposely select four or five bilingual and Latino books connected to themes, such as family, traditions, bilingualism, equity, or a highlighted author. We create a tentative curriculum map with book titles that we think will connect with students and their families. The map is used as an organizational tool and we build space into the map to make changes as we incorporate the interests of students and families into the curriculum.

This map guides our initial selection of literature that is sent home throughout the year (click on map to enlarge). The books for each theme are used for the family literature discussions. These discussions also include family-response journals (lined-notebooks), which are sent home with the second graders. All members of the families are invited to write and/or draw their thoughts and connections to the story in the language of their choice. We also work with the books and the theme through in-school engagements and discussions.

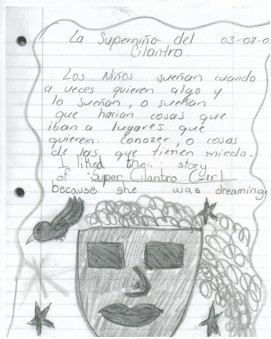

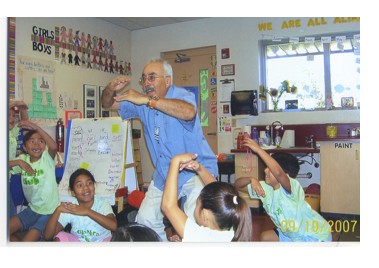

As part of one theme, Robin’s class met Juan Felipe Herrera when he visited their school and helped the students reenact his story Super Cilantro Girl (2003) at a school-wide family picnic. This visit provided the background for the class to read his books, Calling the Doves (1995), The Upside Down Boy (2000), Grandma and Me at the Flea (2002), Featherless (2004), and Super Cilantro Girl (2003). The following entry is from a family-response journal to Super Cilantro Girl.

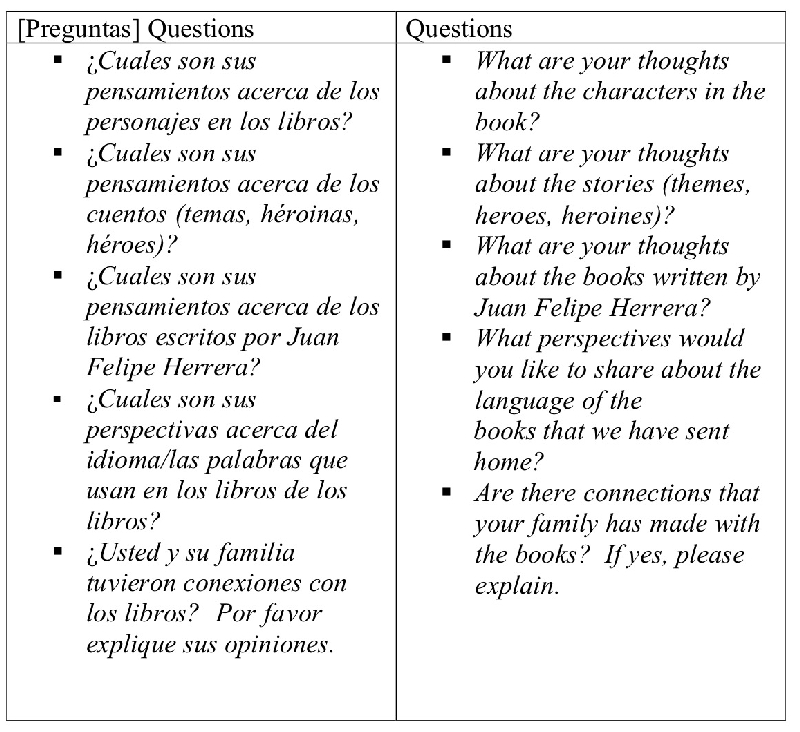

Through our collaboration with families, we hope to gain insights into their perspectives about what makes Latino literature culturally authentic for them (Fox & Short, 2003). Jeanne created a bilingual survey based upon Day’s framework (1997) and Robin collected the surveys from families.

We used thematic analysis while identifying and classifying the families’ perspectives. We looked at the survey responses in terms of topics, meanings, and themes and we attempted to create a picture of collective experiences (Taylor & Bogdan, 1984). We constructed webs of the responses from each survey and identified themes throughout this analysis. We identified four categories of family perspectives related to cultural authenticity: Themes and Stories/Cuentos, Qualities of Characters, Language of the Book, and Local Knowledge of Insiders. Families viewed the stories in the literature as holding importance in terms of relationships and teaching that was muy educativo [very educational]. They examined the strengths of bilingualism and saw language as a resource (Ruiz, 1984), positioning themselves as learners through learning another language. As insiders, they referred to knowledge of cultural membership and details of authenticity.

Themes and Stories: “We are able to enter the story”

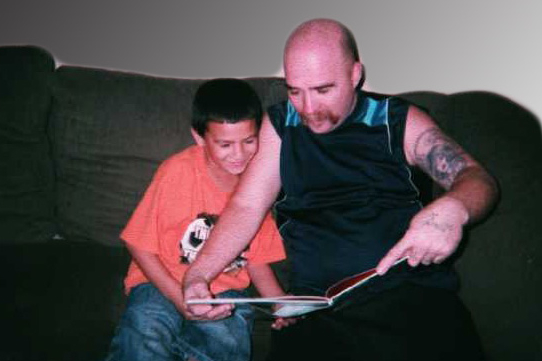

This image of a father reading with his daughter reflects the ways in which our families embraced the books and made strong connections to the relationships present in the stories. They connected to the use of kinship terms in the literature by relating the stories to family members in their own lives (Barrera & Quiroa, 2003). Many families connected to abuelitas [grandmas] from the stories and talked about the heroines in their families. They responded to the theme of goodness by attending to how good triumphs evil in most stories.

The families also attended to the educational nature of the stories in the literature. For them, the books generated enthusiasm for reading because they noticed the consejos [advice] within the stories. The books reflected the ways in which families share local knowledge. Families observed that the stories assisted their children to see the “personal and become better” and that “anything is possible.” Their recognition that stories teach was indicated by comments, such as “Our culture is where we came from.” The stories represented the vibrant history of their ancestors.

Qualities of Characters: “Momento de leer juntos” [“A time of reading together”]

This image personifies families making connections with la gente [people/characters] from the literature. The qualities of the characters from the literature struck a chord with family members who found themselves in those characters. They focused upon what the characters offered in terms of consejos. This relates to how the characters teach their children, particularly in how the characters grapple with adversity. Parents also stated that the characters instilled a love of reading in their children. The “goodness” of characters integrated beauty, good works, and importance. Heroes and heroines were viewed as positive role models. Several families commented that the characters worked hard and often immigrated to the United States from “the other side” (Mexico).

Language of the Book: “We are able to read in Spanish and can read to them in English”

The second grader in this image is responding and making sense of a bilingual text in her response journal. Families reiterated many times that language is a resource in their lives and world (Ruiz, 1984). Our use of bilingual books enriched their own languages as bilinguals. It was significant for the families to have books in more than one language. Families concluded that both languages contributed to their bilingualism and that Spanish assisted them in making sense of English. Language from the literature also led to aprendiendo [learning]. Families indicated that it was good to learn more in English and their children were learning different languages. One family shared, “We are able to read them and we want to read so that I can listen and help write the thoughts that we like in two languages.” Another parent indicated:

I think that this reading project is great and it really helps my child and I to just be together and what better way than reading. I really like the books because we can read them in Spanish and English. My child is learning how to read in English and Spanish. Having the story be in Spanish and English helps me and my child understand the story a lot more.

Another family stated, “We are working together and we share turns reading in whatever language and if I can’t pronounce it the child corrects me and I learn something new. And my child has helped me to learn.” The translations in the literature were not critiqued; instead families emphasized the importance of the presence of two languages in the literature.

Local Knowledge of Insiders: “We are able to connect with the lives of our familias“

This photo was taken when Juan Felipe Herrera visited the school for a daylong author event. The visit culminated in a school-wide picnic where students dramatized one of his stories, Super Cilantro Girl. Families noticed that authors like Herrera wrote books that were based in the knowledge of insiders from their culture. One family indicated, “We are able to connect with the lives of our families in how they live together and eat well and are learning to use my culture with our habit to read. And the books are written in such a way that is simple and we understand the children are like us.” Another parent shared, “It’s a very exciting feeling when reading a book because it makes you closer. It’s awesome and important for her to understand her background as a Hispanic and that if she really wants to be someone she can always make her dream come true, but work for it as well.” Culture was viewed as being passed across different generations and included the resources that families tapped into within their daily life.

Final Thoughts

The meaningfulness and importance of the home/school literature discussions were supported by the parents’ observations and thoughts in the surveys. One parent stated, “The children love the books and look forward to spending quality time sharing them and discussing them. It has been a very enjoyable experience for us.” As teachers and as researchers, it affirmed that bilingual parents should be utilized as a resource in supporting their children’s literacy. Given the opportunity and resources, families provided rich literacy experiences for children in their homes. It also affirmed the importance of allowing parents to share their thoughts related to their own child’s learning. The surveys provided many insights that would not have been heard without the invitation. We intentionally selected books that we thought were authentic and would relate to the lives of the children and their families. The parents’ comments showed us the power of their perspectives as connected to Latino literature.

References

- Barrera, R. & Quiroa, R. (2003). The use of Spanish in Latino children’s literature in English: What makes for cultural authenticity? In D. Fox & K. Short (eds.), Stories matter: The complexity of cultural authenticity in children’s literature, (pp. 247-268). Urbana, IL: NCTE.

- Day, F. (1997). Latina and Latino voices in literature. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Fox, D. & Short, K. (Eds.). Stories matter: The complexity of cultural authenticity in children’s literature, p 3-24. Urbana, IL: NCTE.

- Herrera, J.F. (1995). Calling the doves /Canto a las palomas. San Francisco: Children’s Book Press.

- Herrera, J.F. (2000). The upside down boy/El niño de cabeza. San Francisco: Children’s Book Press.

- Herrera, J.F. (2002). Grandma & Me at the Flea /Los Meros Meros Remateros. San Francisco: Children’s Book Press.

- Herrera, J.F. (2003). Cilantro girl / La superniña del cilantro. San Francisco: Children’s Book Press.

- Herrera, J.F. (2004). Featherless/Desplumado. San Francisco: Children’s Book Press.

- Ruiz, R. (1984). Orientations in language planning. NABE Journal, 8(2), 15-34.

- Taylor, S.J., & Bogdan, R. (1984). Introduction to qualitative research methods: The search for meanings. New York: John Wiley.

Jeanne G. Fain is a research associate at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, TN. Robin Horn is a second grade teacher at Galveston Elementary School in Chandler, AZ.

WOW Stories, Volume II, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesii1/.