Challenging the Hidden Curriculum:

A Middle School Teacher’s Use of Multicultural Literature in the Classroom

Summer Edward with Debra Repak

Folk Arts-Cultural Treasures School (FACTS) is a community-oriented public K-8 charter school located in Chinatown North, Philadelphia. It is an immigrant-focused Charter school with a predominantly Asian-American student body (Chinese, Vietnamese, Indonesian, Cambodian, Laotian and Hmong heritage). Many of the students are English Language Learners (ELLs). African-American, Latino and white students are in the minority, comprising 29 percent of the student body. The school places a high emphasis on diversity and cultural exchange, with a curriculum that emphasizes folk arts education and connections to ethnic and home culture.

Debbie Repak is the seventh and eighth grade Reading and Writing Teacher at FACTS. As a student teacher, I worked in her classroom and became interested in her use of multicultural literature with students. Previously, Debbie worked as a Humanities teacher at Welch Elementary School in the Council Rock School District. As a white, middle class teacher, she has worked hard to build bridges with Asian-American, African-American and Latino students from low-income, working class and immigrant families.

Multicultural Literature: A Teacher’s Lens

Kruse and Horning (1990) define multicultural literature as “books about people of color.” Rudine Sims Bishop (1997), a pioneering multicultural education scholar, defines multicultural literature as books that “reflect the racial, ethnic, and social diversity that is characteristic of our pluralistic society and of the world,” particularly books about the experiences and perspectives of “groups whose histories and cultures have been omitted, distorted, or undervalued in society and in school curricula” (p. 3). When interviewing Debbie, I was interested in her working definition of multicultural literature. She expounded on her understanding of the term:

Multicultural literature means books with characters, settings, plots that are unique to cultures different than my own. The different settings and plot issues truly spring from, and are dependent upon the cultures that they represent. They represent the strengths, weaknesses, preferences, prejudices, ideals, religious practices, economic situations, societal norms, and power structures between sexes in the family and society that are truly present in these cultures. They also represent the clothing, music, traditional foods, language patterns and social mores that are part of that culture.

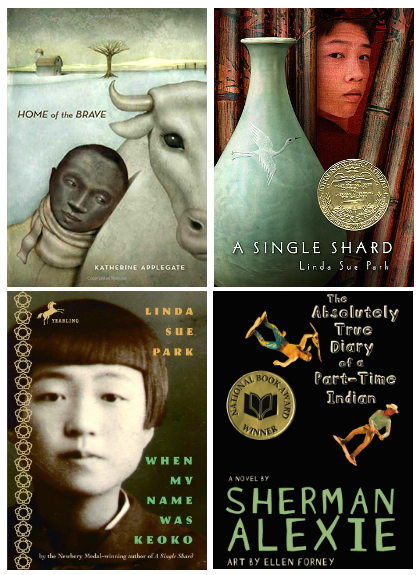

Some of Debbie’s favorite multicultural books are those by picture book authors and illustrators like Patricia Polacco and Floyd Cooper. She admires books by Walter Dean Myers, Christopher Paul Curtis, and Jaqueline Woodson. Sherman Alexie’s The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian (2007) is a personal favorite. She also likes the Bluford High Series, which she describes as “lightweight on real literary merit, but full of characters and situations my African-American students can relate to and love.” Books written by or about Asian-American children or young adults she considers ground-breaking are those by Linda Sue Park (e.g. A Single Shard and When My Name Was Keoko) and Laurence Yep, which she describes as having “wonderful, strong characters.”

Debbie shared her beliefs about the teacher’s role in creating a classroom environment where students feel safe to engage with such texts. She believes that teachers need to become cross-culturally competent by doing the challenging but necessary work required to have respectful culturally sensitive exchanges with students. Owning one’s cultural identity and issues, a willingness to step outside of one’s comfort zone, and maintaining a mindset of curiosity and inquiry, must be a part of a teacher’s stance. Debbie’s following comment illustrates some of these complex issues:

Teachers need to think of the kids they have in front of them — get to know their thoughts, experiences, feelings, cultural situations and backgrounds so that they can select works that click with them. They need to know that it’s ok to make a mistake now and again, as long as you’re open to what went wrong and it reshapes your teaching. It’s important to examine your prejudices, and examine why you choose one piece over another — make sure it’s a good choice for the student as well as you. You have to respect other cultures, but not be afraid to be open and honest, admitting what you don’t know or aren’t familiar with. Sometimes, you have to do some homework — find out a little more about things mentioned in the literature so you can explain it or treat it respectfully.

Like many K-12 literacy teachers, Debbie is aware of existing critiques of multicultural education and the pedagogical perspectives which underlie such critiques. For example, it has been argued that the effort to incorporate ethnically diverse literature in the classroom has led to “dumbing down” student textbooks and has limited children’s knowledge and overall literacy. In her response to this argument, Debbie suggests that teachers have to balance their use of inclusive literature with methodologically-sound literacy instruction:

I understand the criticism, because sometimes in the rush to be ethnically diverse, teachers have chosen trite, tired or just poorly written literature. They have presented it in a condescending way — almost “Here’s a good book, see — there’s an African-American (or Chinese or Mexican) person, just like you!” instead of, “Here’s a great story, a well written piece of literature that provides a particular perspective.” Also in the rush to be diverse, the teaching of English language arts has done itself a great disservice by often eliminating direct and specific instruction in the nuts and bolts of grammar and writing. If children’s knowledge is watered down, it is because this instruction is spotty or non-existent at best in many schools. I meet far too many student teachers who make basic grammatical and spelling mistakes that wouldn’t have been allowed by my 8th grade teacher.

Another criticism of multicultural literature is that its value is compromised because there are not enough broadly-based novels featuring characters who are people of color in “mainstream” roles. For example, books with Asian-American characters tend to be narrowly confined to issues of immigration, language barriers or racism, which can lead to what Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie calls “the danger of a single story” about Asian-Americans. Debbie commented:

I think this is true; I am seeing more books where Asian-American characters deal with the immigrant parent viewpoints and Americanized child culture clash; although “generation gap” is a theme no matter what the race. I don’t see a lot of people talking about it at FACTS, but I have observed that the stress Asian-American parents place on their children to conform and succeed within the educational structures as they presently exist does not encourage a desire to be proud of, or to promote, their own culture. Also, my students are typical teens. They want popular books that deal with the universal struggles of being a teen, before they like ones with cultural significance. I think that they do enjoy reading stories with Asian-American characters, but will not seek them out specifically. I see these students with typical first generation attitudes — the desire to fit in trumps the desire to maintain their cultural legacies. I think FACTS is so important for carrying these students through this time, surrounding them with strong Asian culture and pride, where they might not feel that yet on their own.

Thus, rather than reinforcing cultural stereotypes, multicultural education and literature must play a role in helping students from diverse backgrounds to embrace the full spectrum of who they are, and counter the dismantling of their identities. Teachers need to incorporate a diversity of narratives when they select multicultural books for instruction or inclusion in the classroom library.

The Role of the Classroom Library

In Debbie’s classroom, students are encouraged to read a wide range of books. There are many multicultural children’s and young adult books that students can check out from the classroom library. Several of the book bins in the classroom library are devoted exclusively to books by African-American authors; for example there is a Bluford High bin for that popular teen series, and a bin with books by Jacqueline Woodson, an award-winning African-American author.

There are also several bins devoted to books written in Chinese and Korean. Some of these are books by American authors that have been translated, and some are books by Chinese and Korean authors. Browsing through the library, I found English-language picture books and middle grade novels about Asian-American, Native-American, Latino, African-American and Jewish experiences. I also found one or two examples of Inuit literature.

A clear majority of books in the classroom library are books about white, middle-class experiences. I noticed that the students check out these books the most. Fantasy, science fiction and books marketed as girl-centric fiction — genres that suffer from a lack of authors and characters of color — are popular with the seventh graders. The eight graders tend to check out more realistic books, but again, usually steer clear of realistic books with characters of color.

Finding and Selecting Multicultural Literature

When Debbie selects multicultural literature for instruction or as assigned reading, she draws upon her knowledge of suitable books, accumulated over years of classroom teaching. She also learns of books through conversations with other teachers. She owns a few annotated and selected multicultural literature bibliographies which she references. Occasionally, Erin, the school’s Reading Specialist, will recommend a book that Debbie will then research and possibly buy. Like many elementary and middle school teachers across America, Debbie relies mainly on Scholastic’s Classroom Wish List program to purchase books for her classroom, but also makes use of donations and thrift store and garage sales. Thus, Scholastic Books determines, to a great extent, which multicultural books are found on the shelves of the classroom library. Many teachers and parents have noted that Scholastic’s catalog and school book fairs do not provide enough diverse offerings.

Debbie clearly views herself as someone who selects, rather than censors multicultural literature, fitting Asheim’s (1953) description of the positive selector who looks for reasons to keep a particular book. In talking to me about the Bluford High series, it was clear that Debbie looks for values and strengths in the books to overshadow the minor objections she has about them.

She also told me that another teacher had given her a negative review of the book 12 Brown Boys (Tyree, 2008), a collection of unrelated short stories about 12 African-American preteen boys. The teacher had taken issue with the cover of the book and the title, and the fact that its author is well-known for writing adult books with mature themes. Debbie decided to read the book herself and eventually added it to her classroom library. This willingness to judge books by their internal values is typical of selectors who resist the urge to put their own values and beliefs before those of others when selecting texts to use in the classroom (Asheim, 1953, p. 66).

Like any selector, Debbie also has faith in the intelligence of students and clearly respects their liberty of thought. She reported that some of the stories and poems that she has shared with students have shocked them. She knew the material would be shocking but decided to use it to promote dialogue. She thinks of students as rational, astute people who have a right to read what they want. At the same time, she acknowledges the trickiness of using books that have been the target of censorship. She believes that the onus is ultimately on parents to make decisions about what they want their children to be reading.

Debbie communicates with parents about students’ reading material through the nightly reading log. In their reading logs, students list the title and author of the book they are reading and write a comment about it. From the earliest grades at FACTS, parents are encouraged (in written notices, at parent workshops called Family Reading Nights, and at the Parent/Teacher Conferences that are held twice a year ) to ask their children about their reading. Parents are provided with conversation starter questions such as: “Tell me about what’s happening. Who’s your favorite character? What is your favorite part so far, and why?” The seventh and eighth graders write a reading response (five sentences) each evening and parents are invited to read these responses. As Debbie’s comment below reveals, the reading log is an important tool for helping students master the art of book selection:

If parents do not understand written English, students can translate what they have written for parents. Of course, they can respond to questions in the parents’ preferred language. With so many parents who are English Language Learners, we as a school are proactive in enabling students to think carefully about their book choices. Developmental Reading Assessment (DRA) tests for reading levels are administered at least three times a year, and students are encouraged to select books at their reading level so they will make the most progress in their reading. We teach the students to read the book jackets/blurbs and a page or two of the book to see if it interests them. We teach them about genre characteristics and to notice which genres they prefer. We teach them about author’s style and to notice which authors’ styles they like. Armed with this type of knowledge about their reading abilities and habits, students are more likely to make effective book choices. Each English Language Arts (ELA) teacher works hard to be sure they have a variety of books available to students at their appropriate level. Since many parents are not confident English speakers, they depend on us to usher their children through the book selection process.

Given that FACTS has a student body that is predominantly Asian-American, I wondered if Debbie placed a high priority on selecting Asian-American fiction. To use Sims Bishops’ (1997) much-quoted metaphor, such books would serve as “mirrors” for Asian-American students, providing them with opportunities to reflect on their own cultures and experiences, and would act as “windows” through which students from other ethnic backgrounds could observe their classmates’ cultures and ways of perceiving the world. Debbie’s comment below sheds light on how district-mandated approaches to literacy instruction may limit or complicate the teacher’s desire to create a more inclusive reading curriculum:

Honestly, the [Columbia Teachers College] Readers Workshop model does not allow me to teach fiction using specific works of literature, except in short passing references. We do read novels, but they are by genres, not chosen only for cultural diversity and there are many different small book groups in each class, so no one class has a shared book (unless it’s a read-aloud or short story). We try to choose literature that represents all cultures, but we could use more. I have noticed informally, that most of my Asian-American students will not self-select books with Asian or Asian-American characters, preferring other traits [over cultural significance]. Naturally, it would be important to choose characters of all ethnic backgrounds for students — the more exposure to cultures and other ways of thinking the better. It certainly helps break down negative stereotypes, and build pride in one’s own culture.

Teaching Multicultural Literature: Strategies and Practices

Debbie uses a variety of strategies to incorporate multicultural literature into the seventh and eighth grade reading and writing curriculum. By coming up with creative ways of using texts in the classroom, she seeks to give status to multicultural literature, build students’ cross-cultural competencies, encourage critical dialogue, and help students make powerful connections to texts.

Read-alouds are a standard part of Debbie’s instructional approach, and have proven to be an effective method for getting students engaged with books they would be reluctant to read otherwise. She once did an extended read-aloud of the book Home of the Brave (Applegate, 2007), the story of a boy who is a refugee from the Sudan and his struggles to relate to a different culture. She recalls the enthusiasm of students:

Although the personal struggle might have been the main focus, the [main character’s] longing for the culture of his home and references to it were important. My goal was to expose students to a great book, first and foremost. Since so many are immigrants, others are of African-American descent, and all are teens, this book was one they could relate to at many different levels. In my school, I feel it is very important to bring in characters that embody many different ways of thinking — and have a connection to the most students possible. So many are disenfranchised in many ways and choosing characters they can relate to is one small way to respect and acknowledge them. The kids really enjoyed and seemed to relate to the main character’s struggles to fit in while being different; they would beg for the story to be read.

In another instance, students read a short story by Laurence Yep, a Chinese-American writer, about his childhood and analyzed how character is revealed. As Debbie recalls, the story was well-received by both of the dominant cultures in the classroom:

It was very accessible to Chinese-American students because it described an experience they actively participate in, running a store and being part of a family. The African-American students also related to the struggles of the Dad in the story where he had to settle things with his fists at times. I was very comfortable with the material. Well-written literature has a universality that transcends culture, while still transmitting it. I feel like I have a stronger lesson when students can relate to the characters in the literature I present.

Debbie has also used short stories by Sandra Cisneros and Gary Soto, and poetry by Alvin Lau and many African-American poets, like the “dream poems” by Langston Hughes. As she observes: “these authors seem to empower kids to use their own voice to share their lives.”

I noticed that Debbie does not confine her use of multicultural literature to cultural and ethnic heritage months. Observance months such as Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month and Black History Month can remind educators to highlight the achievements of specific cultures and provide an opportunity for students from those cultures to feel celebrated and valued, but if educators only feature “diverse books” for one month per year, they end up putting people and books in a box. Debbie actively avoids doing this by connecting multicultural literature to a broad range of curricular themes. Her cross-curricular approach integrates multicultural literature with the teaching of literacy skills, core subject areas and Common Core State Standards throughout the year. She eschews a reductionist conception of diversity by identifying ways that multicultural books apply to everyday, universal experiences. Debbie’s comment on the universality of good literature, and the variety of her teaching strategies, illustrates her commitment to broadening the diversity frame:

I was thinking about your last question — how I motivate multicultural literature choice — and I have to say, it’s not very different from how I’d present any book. Good literature is not hard to sell. I use book talks, peer recommendations, sometimes book trailers, videos/print copies of author interviews, enthusiastic personal endorsements, previews of the author’s website, and inclusion of multicultural books in book club book selections. Once students start reading a book, the excitement spreads, students clamor for the book, and I get extra copies. It’s hard not to love a book frenzy!

Conclusion

My interview with Debbie provides much insight into what is necessary when using multicultural literature in the classroom to achieve its proper ends. Her comments relate to Louie (2006), who says, “teachers need principles to guide students toward understanding multicultural stories” and that “simply exposing children to multicultural literature may lead to indifference, lack of understanding and even resistance” (p. 438). Effective teachers are continually refining their toolbox of strategies and best practices for using multicultural literature in the classroom. They are also constantly honing their criteria for selecting multicultural literature that speaks to unique sets of students. I agree with Debbie that the best way to do this is a) through critical self-reflection of one’s own teaching; b) by knowing students and listening to their voices, and c) by keeping a sharp eye on discussions in the teaching field and on literary developments.

Debbie reminded me that good teachers play an active role in helping their students develop cross-cultural understanding and critical consciousness through personally meaningful engagement with multicultural literature (McNair, 2003). Such teachers realize that the right multicultural books can and should be used to “invite conversations about fairness and justice” and “encourage young people to ask why some groups are positioned as ‘others’” (Leland, et al., 1999, p. 70). As teachers go beyond the role of merely being a selector of multicultural literature to being a facilitator of critical literacy in their classrooms, they use multicultural books as critical texts to “build students’ awareness of how systems of meaning and power affect people and the lives they lead” (Leland, et al., 1999, p. 70).

Talking to Debbie also made me realize just how important it is for teachers to see the hidden curriculum in their classrooms. McNair (2003) defines the hidden curriculum as “the subtle and not-so-subtle messages that are not a part of the intended curriculum, [but which] may also have an impact on students” (p. 46). In Debbie’s case, she sees how the Readers Workshop Model mentor texts and individualized approach do not readily provide a variety of multicultural literature to share with the entire class group as a whole on a regular basis. Knowing this, she commits herself to working within and around the constraints of the Readers Workshop Model to inject multicultural literature and critical literacy into her lessons and students’ self-selected reading choices wherever she can. As teachers like Debbie become aware of and find ways to challenge the “hidden curriculum of hegemony,” they are able to avail themselves and their students of multicultural literature’s transformative possibilities (Jay, 2003, p. 3).

References

Asheim, L. (1953). Not censorship but selection. Wilson Library Bulletin, 28 (September), 63-67.

Jay, M. (2003) Critical race theory, multicultural education, and the hidden curriculum of hegemony. Multicultural Perspectives, 5(4), 3-9.

Kruse, G.M., and Horning, K.T. (1990). Looking into the mirror: Considerations behind the reflections. In M. V. Lindgren (Ed.), The multicolored mirror: Cultural substance in literature for children and young adults. Fort Atkinson, WI: Highsmith.

Leland, C., Ociepka, A., Harste, J., Lewison, M., & Vasquez, V. (1999) Exploring critical literacy: You can hear a pin drop. Language Arts, 77(1), 70-77.

Louie, B. Y. (2006) Guiding principles for teaching multicultural literature. Reading Teacher, 59(5), 438-448.

McNair, J. C. (2003). “But the five Chinese brothers is one of my favorite books!”: Conducting sociopolitical critiques of children’s literature with preservice teachers. Journal of Children’s Literature, 29(1), 46-54.

Peterson, B., Gunn, A., Brice, A., & Alley, K. (2015). Exploring names and identity through multicultural literature in K-8 classrooms. Multicultural Perspectives, 17(1), 39-45.

Sims Bishop, Rudine. (1997). Selecting literature for a multicultural curriculum. In Violet J. Harris (Ed.), Using multiethnic literature in the K-8 classroom (pp. 1-20). Norwood, MA: Christopher Gordon.

Cited Children’s and Young Adult Books

Alexie, S. (2007). The absolutely true diary of a part-time Indian. New York: Little Brown.

Applegate, K. (2007). Home of the brave. New York: Feiwel and Friends.

Park, L. S. (2001). A single shard. New York: Clarion.

Park, L. S. (2002). When my name was Keoko. New York: Clarion.

Tyree, O. (2008). 12 brown boys. East Orange, NJ: Just Us Books.

Recommended Multicultural Children’s and Young Adult Literature

Cisneros, S. (1994). The house on Mango Street. New York: Knopf.

Curtis, C. P. (2004). Bucking the Sarge. New York: Wendy Lamb.

Curtis, C. P. (1995). The Watsons go to Birmingham–1963. New York: Delacorte.

Folan, K. L., & Langan, P. (2012). Bluford High. Breaking point. New York: Scholastic.

Folan, K. L. (2013). Bluford High. Pretty ugly. New York: Scholastic.

Grimes, N. (1994). Meet Danitra Brown. Illus. F. Cooper. New York: Lothrop, Lee & Shepard.

Hughes, L. (2012). I, too, am America. Illus. B. Collier. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Kern, P. (2012). Bluford High. No way out. New York: Scholastic.

Polacco, P. (1992). Chicken Sunday. New York: Philomel.

Polacco, P. (1994). Pink and Say. New York: Philomel.

Polacco, P. (2012). The art of Miss Chew. New York: Putnam.

Polacco, P. (1988). The keeping quilt. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Soto, G. (1990). Baseball in April and other stories. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich

Soto, G. (2005). Help wanted: Stories. Orlando: Harcourt.

Sherman, P. (2010). Ben and the emancipation proclamation. Illus. F. Cooper. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

Langan, J. (2012). Bluford High. Search for safety. New York: Scholastic.

Langan, P. (2002). Payback: Bluford High. New York: Scholastic.

Mason, M. (2010). These hands. Illus. F. Cooper. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Myers, W. D. (1983). Hoops. New York: Dell.

Myers, W. D. (1988). Scorpions. New York: Harper & Row.

Woodson, J. (2015). Brown girl dreaming. New York: Penguin.

Woodson, J., (2012). Each kindness. Illus. E. B. Lewis. New York: Nancy Paulsen Books.

Woodson, J. (2007). Feathers. New York: Putnam.

Woodson, J. (1998). If you come softly. New York: Putnam.

Woodson, J. (2000). Miracle’s boys. New York: Putnam.

Woodson, J. (2005). Show way. Illus. H. Talbott. New York: Putnam.

Summer Edward, MSEd., is the Foundress and Managing Editor of Anansesem Caribbean children’s literature ezine, a Highlights Foundation alumna, and a former judge of Africa’s Golden Baobab Prizes for children’s literature.

Debra Repak is a seventh and eighth grade English Language Arts teacher at the Folk Arts-Cultural Treasures Charter School in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

WOW Stories, Volume V, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/v1.