By Carmen M. Martínez-Roldán & William García

Latino children’s literature in the United States refers to literature written by Latino and Latina authors, whether in English or Spanish and regardless of the topics they address (Ada, 2003). Giving the great intragroup differences in social class, immigration patterns, and language practices among Latinos, we would expect Latino literature to reflect such diversity, but there is still a long way to go to meet that goal. This month the Blog will focus on Latino literature that contributes to and illustrates the diversity of Latino communities as reflected in children’s and young adult literature. Each week I’ll invite students from Teachers College to share their thoughts about this literature. We will start the first two weeks by focusing on literature that highlights the experiences of Afro-Latinos and Afro-Caribbean communities. Afterwards, we will focus on Latino literature that addresses in some way indigenous communities. This first week, graduate student William García will share his thoughts about Eric Velasquez and the potential of his work to support Racial Literacy in classrooms.

Latino children’s literature in the United States refers to literature written by Latino and Latina authors, whether in English or Spanish and regardless of the topics they address (Ada, 2003). Giving the great intragroup differences in social class, immigration patterns, and language practices among Latinos, we would expect Latino literature to reflect such diversity, but there is still a long way to go to meet that goal. This month the Blog will focus on Latino literature that contributes to and illustrates the diversity of Latino communities as reflected in children’s and young adult literature. Each week I’ll invite students from Teachers College to share their thoughts about this literature. We will start the first two weeks by focusing on literature that highlights the experiences of Afro-Latinos and Afro-Caribbean communities. Afterwards, we will focus on Latino literature that addresses in some way indigenous communities. This first week, graduate student William García will share his thoughts about Eric Velasquez and the potential of his work to support Racial Literacy in classrooms.

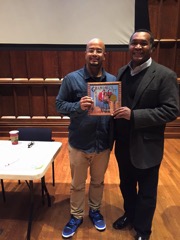

“The number of Afro-Latino children’s book writers is scarce and stories surrounding Afro-Latino experiences are also uncommon. On March 1st 2016, the towering presence of Eric Velasquez changed the social landscape of Teachers College at Columbia University. Velasquez, an Afro-Puerto Rican author and illustrator of children’s literature, highlights the need to further discuss Afro-Latino narratives. On the one hand, books revolving around black children often refer to African American or African narratives that leave out the experiences of black children who come from Latin America. On the other hand, Latino picture books tend not to use black characters or emphasize the African heritage in Latin America. Surprisingly, not only is Velasquez himself Afro-Puerto Rican but he also writes about Afro-Latino and African American narratives. I had the pleasure to speak to him after his fantastic presentation at Teachers College. He was humble, charismatic, constantly smiling and was authentically listening to others. Being around him emitted a sense of good-heartedness. I told him that I wish there were more Afro-Latino artists out there and he nodded in agreement. Velasquez signed the picture book Grandma’s Gift that I had brought with me, which said: ‘Remember to always share the gift!’

“The number of Afro-Latino children’s book writers is scarce and stories surrounding Afro-Latino experiences are also uncommon. On March 1st 2016, the towering presence of Eric Velasquez changed the social landscape of Teachers College at Columbia University. Velasquez, an Afro-Puerto Rican author and illustrator of children’s literature, highlights the need to further discuss Afro-Latino narratives. On the one hand, books revolving around black children often refer to African American or African narratives that leave out the experiences of black children who come from Latin America. On the other hand, Latino picture books tend not to use black characters or emphasize the African heritage in Latin America. Surprisingly, not only is Velasquez himself Afro-Puerto Rican but he also writes about Afro-Latino and African American narratives. I had the pleasure to speak to him after his fantastic presentation at Teachers College. He was humble, charismatic, constantly smiling and was authentically listening to others. Being around him emitted a sense of good-heartedness. I told him that I wish there were more Afro-Latino artists out there and he nodded in agreement. Velasquez signed the picture book Grandma’s Gift that I had brought with me, which said: ‘Remember to always share the gift!’

In Grandma’s Gift, Velasquez, narrates a story inspired by his experiences as a child with his grandmother. An Afro-Puerto Rican boy called Eric, like the author, is celebrating the Christmas holiday with his grandma by making pasteles, a Puerto Rican savory dish made of green banana, green plantain, and various root vegetables:

In Grandma’s Gift, Velasquez, narrates a story inspired by his experiences as a child with his grandmother. An Afro-Puerto Rican boy called Eric, like the author, is celebrating the Christmas holiday with his grandma by making pasteles, a Puerto Rican savory dish made of green banana, green plantain, and various root vegetables:

‘All the vendors knew that Grandma would buy only the best ingredients for her famous pasteles,’ said Eric.

Because the pasteles dish has many African influences, Velasquez hints at the intergenerational transmission of Afro-Caribbean traditions getting passed from his grandmother to him, the grandson. Another scene in the book, which underscores the importance of Black racial pride takes place when Grandma decides to take Eric to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. For the first time, Eric discovers that he can become an artist if he really wants to:

‘I quickly ran up and read the caption next to it. Grandma, it says Juan de Pareja was a slave and an assistant to the great painter Diego Velázquez. He later set Pareja free, and de Pareja became a great artists himself.’

What I find interesting about Velasquez’ writing style is the way in which he introduces topics involving issues of race, black culture and racism in child-friendly ways. Velasquez creates racial literacy for Latino students who may not be aware of racial hierarchies and the process racialization. According to Ladson Billings cultural relevant pedagogy is characterized as teaching that empowers students intellectually, emotionally, socially and politically by using cultural referents to impart knowledge, skills and attitudes. This teaching helps black students develop different ways of being black and Latino in a way that helps the students understand themselves and strive for academic excellence. Afro-Latino students must be taught how to identify and overcome micro-aggressions that are experienced daily and literature can play an important role in this process. Howard Stevenson also proposes that the goals of Racial literacy are the strategic deconstruction of racial information and knowledge, the building of healthy, cross-and-same racial relationships, the flexible reconstruction of racial identity, the willful, choosing of racial styles and self-expression, and the assertive countering of racial stereotypes.

Talks of race and racialization remain a taboo discussion topic in some Latino communities and remain, for the most part, silenced also in children’s literature. This type of silence harms society and prevents meaningful dialogues among members of communities in and outside schools. In this sense, Velasquez’ work is paving the way for new possibilities regarding black and Latino children’s literature. Black students in the United States are commonly referred to as simply African American without taking into account Afro-Caribbean and Afro-Latino students. I believe that Latino literature through Velasquez’ work is becoming more culturally responsive. We need as educators to get involved with Afro-Latino students, our history and the way we occupy space in the Americas in order to address this gap in education. Using Velasquez’ work in classrooms is a great resource for pushing the boundaries against narratives that simplify Latino and black identities.”

Other books by Velásquez that would support racial literacy include Grandma’s Records and My Friend Maya Loves to Dance. We would like to hear from those of you who have used literature in the classroom addressing the experiences of Afro-Caribbean or Afro-Latino children. Have you found powerful books with potential to support Racial literacy in classrooms?

Ada, F. (2003). A magical encounter: Latino children’s literature in the classroom (2nd. ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Ladson Billings, G., & Tate, W. (1995). Toward a criticial race theory of education. Teachers College Record, 97, 47-68.

Stevenson, H. C. (2014). Promoting racial literacy in schools: Differences that make a difference. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Sue, D. W. (2015). Race talk and the conspiracy of silence: Understanding and facilitating difficult dialogues on race. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Journey through Worlds of Words during our open reading hours: Monday through Friday 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., Saturday 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. Check out our two online journals, WOW Review and WOW Stories, and keep up with WOW’s news and events.

- Themes: Carmen M. Martínez-Roldán, William García

- Descriptors: Books & Resources, Debates & Trends, Student Connections, WOW Currents

Thank you for this bringing up this very important topic. There is definitely a need for more Afro-Latino children’s literature, the problem is exactly as you describe–books either examine the African American experience or the experience of Latinos not directly, visibly or culturally of African descent. I have struggled to find books for the young ones in my life. I would suggest Josefina Baez’s children’s book, Why is my name Marysol?, which focuses on a young Afro-Dominican girl on the island. Thank you!

I have to be honest, all through my educational career I have seen very little if any Latino inspired literature. I never gave it much thought when I was growing up or even in college, but now that I am a teacher serving the needs of a diverse class of students it is concerning. If the scarcity of Latino literature wasn’t enough to give me pause, the overwhelming scarcity of more diverse pieces such as Afro-Latino literature is even more alarming. Students need to read books about others who are like them. They need authors and characters to identify with. There is an almost infinite amount of literacy texts about whites and there is even an increasing amount of literature about African Americans and a growing number of African American authors, but your article makes me reflect about the other people groups that make up our great nation and my classroom. If literature is a voice then it would seem that minority groups are all but silenced. I am inspired to see more authors of any and all minority groups stepping up and getting their work out there for all to see. You can relate too many of my minority students in a way I just never will. For them to see and read books about others of their ethnicity and to see authors of their ethnicity rising up is very empowering for them. At a time where we as educators are trying harder than ever to make texts relatable to their students, your literature matters and it is priceless. Keep writing and keep encouraging others to write and I will be doing the same in my classroom using your books to open the doors in the minds of my students.

What a great way to incorporate a history lesson in the ELA classroom. I appreciate the author Eric Velasquez for taking action in promoting and helping minorities, as well as other ethnic groups relate to the realities of difference and sameness in our country. I am disappointed in knowing that Afro-Caribbean, and Afro-Latino students are simply classified as African-Americans. This information should enlighten us all in realizing that there is a need for an extended curriculum that will address multiple perspectives rather than a westernized ideal of what it takes to get students engaged with texts. As a teacher, I can relate with to what it looks like when a student notices someone that looks like them in a textbook; leaving me with mixed emotions. I’m excited because I witness a student who for whatever reason has no desire to read, connect with a text. Then on the other had, I am disappointed, because I’m not sure when or if I will ever get to witness that moment of enlightenment with that student. However, I believe this can be made possible by teachers who are advocates for ensuring that students are making meaning connections with texts. As for me, I have taken the initiative this year to ensure that I have at least three books in my classroom library for each student that I teach to be able to relate with. A major role in literacy instruction is for teachers/instructors to understand that if you make reading relevant to the student you have won half the battle. In closing, I would like help bridge the gap regarding diversity in young adult literacy. Things in our world are evolving and so must we. Thank you for taking the time to read my post.

Sincerely,

Jason Powell

I appreciate all the comments so far. I agree with every single one of you. I firmly believe that the ongoing dichotomizing of Black with Latino ignores the bigger complexity of Latin America and Latinos in the United States. Right now in New York we have a solid Garifuna population, many who are from Honduras, Guatemala and Belize. In New York, we have a thriving young Afro-Dominican population that is claiming afro-descendance. This helps to reduce the tensions between Haitians and Dominicans. For many Afro-Latinos, Black and Latino are not separate entities. The same goes in countries like Panama, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Colombia, Brazil and so forth. We tend to view Blackness as something of the past, a folkloric past that is only useful for either nationalism or branding claims of mestizaje. Seldom, are topics of lived experiences as a black body part of the conversation. Afro-Latino children’s literature would be a great bridge to increase solidarity with African Americans and other marginalized people in the United States. Politically speaking, dichotomizing Latino and Black (African American) is beneficial for many but as educators we need to place emphasis on the importance of our students not some political gain or fighting over resources. as educators we become key agents in helping students racialize themselves while also understanding how the world views them. I believe we need to become part of the solution and not the problem. Simply saying: “Black is Black why are you complaining?” “why are being divisive? or “you’re not really Black” ignores the importance of particular cultures and experiences (particularly Black migrant experiences), that requires a culturally and linguistically approach. Also, Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, Juano Hernandez, Carlos Cooks, Felipe Luciano, (we need more research on Afro-Latina women) Graciela who played for Machito and his Afro-Cuban jazz bands in Harlem among others are all part of African American history as well as Latino history. Although, this is going to cause confusion and resistance, as educators, we need to broaden this conversation because their remains a lot of racism and micro-agressions amongst Latinos and that is something we have to deal with in the 21st century.