Yoo Kyung Sung, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM and Junko Sakoi, Tucson Unified School District, Tucson, AZ

Two Faces of Digital Prosperity

Two Faces of Digital Prosperity

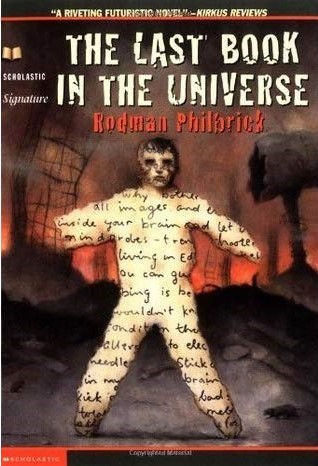

We saw them and decided to name them Reluctant Printed–Text Readers (RPR). RPR are comfortable with reading texts in digital spaces, but are readers who feel reluctant and resistant to reading printed texts. They do literacy practices in digital spaces, but don’t assess their literacy practice as reading because they usually read on those digital gadgets. They hardly enjoy reading texts on paper. In 2001, Marc Prensky claimed, “Our students have changed radically. Today’s students are no longer the people our educational system was designed to teach,” (p.1). Prensky’s expression of “change” indicates K–college students being digital generations whose surroundings are all some types of digital items such as music players, cell phones, video games, tablets, computers, etc. Thus, “Digital natives” grew to be an outdated expression since our students are now all “native speakers.” Now in 2019, we live in the digital era that “okay, Google” or “Alexa” can help you to take care of quick info search, running errands, and other life operations. Young people in our classrooms now have smartphones for their entertainment, research, socializing, reading, etc. Books are not a comfortable “thing” to some or many young readers. The fantasy book, The Last Book in the Universe by Rodman Philbrick (2002) may no longer be a fantasy.

Reading printed texts like a paper book grew to be unattractive to many young readers. Social networks like Snapchat, Twitter, and Instagram emphasize their text consumption cultures that are fast and short. Facebook is no longer a “hip” website but instead is as known as or “A.K.A.” an old people site. Reading books to young people may mean they will face longer text reading in a longer time period. Eventually, long texts indicate a boring time for young readers.

Attracting 8th Graders with Features to Challenge the Boundaries

Prensky (2001) describes digital Immigrants who “learn like all immigrants, some better than others to adapt to their environment, they always retain, to some degree, their ‘accent,’ that is, their foot in the past,” (p.2). This month, we take the journey of “digital immigration” in an 8th grade classroom. Most of the 8th graders we met in this school in Tucson hate books. By this we mean they hate reading books and they surely don’t read for fun. Their school grade is not impressive because it reflects students’ reading realities. Junko Sakoi at the TUSD and I will use different digital gadgets in small to big scales to attract the 8th grade–readers who know the fear or struggles they have around reading. It is not a matter of teaching reading and teaching literature anymore. It is a matter of how we attract readers by bridging digital literacies to traditional ones. Teachers may feel some kind of mission assigned to them with a big question, how shall we have our students taste and experience the “sweetness” of book reading?

For the next two weeks, we will share our stories of visiting a library at Magee Middle School in Tucson to introduce the drama–based library environment that attracts young readers with a visually enhanced library environment. The following weeks, we meet the librarian who successfully responds to young readers’ needs in the digitally dominating literacy world of teenagers. The final two weeks we will share our audio book project that attracts our 8th graders to expand boundaries they passively built with mixed fears of book reading and memories of being judged with their reading assessment results from their childhood.

References

Philbrick, W. (2000). The Last Book in the Universe. New York: Blue Sky Press.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants Part 2: Do They Really Think Differently? On the Horizon, 9(6), 1.

Journey through Worlds of Words during our open reading hours: Monday-Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit archival stream.

- Themes: Junko Sakoi, Last Book in the Universe, Rodman Philbrick, Yoo Kyung Sung

- Descriptors: Books & Resources, WOW Currents