Celeste Trimble, St. Martin’s University, Lacey, WA

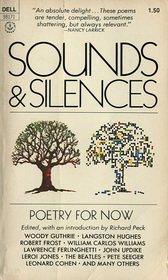

When I was fourteen, I loved poetry. I always loved it, having grown up on a steady diet of recited nursery rhymes and children’s poetry like A Child’s Garden of Verses by Robert Louis Stevenson. But something happened in junior high school: The anthology, Sounds and Silences: Poetry for Now, edited by Richard Peck. I loved that it included song lyrics by Woody Guthrie, Leonard Cohen and The Beatles–verses I recognized. What I really loved about this book was that it was my introduction to writers who shaped and continue to shape how I think about the world, my life and the lives around me. “The Rebel” by Mari E. Evans was practically an anthem for the duration of my adolescence. Langston Hughes, e e cummings, Dylan Thomas, this book was my introduction to modern poetry. But, most importantly, it was my introduction to Gwendolyn Brooks.

When I was fourteen, I loved poetry. I always loved it, having grown up on a steady diet of recited nursery rhymes and children’s poetry like A Child’s Garden of Verses by Robert Louis Stevenson. But something happened in junior high school: The anthology, Sounds and Silences: Poetry for Now, edited by Richard Peck. I loved that it included song lyrics by Woody Guthrie, Leonard Cohen and The Beatles–verses I recognized. What I really loved about this book was that it was my introduction to writers who shaped and continue to shape how I think about the world, my life and the lives around me. “The Rebel” by Mari E. Evans was practically an anthem for the duration of my adolescence. Langston Hughes, e e cummings, Dylan Thomas, this book was my introduction to modern poetry. But, most importantly, it was my introduction to Gwendolyn Brooks.

Brooks’ poem, “To Be in Love,” washed over me, and I found myself falling in love with Brooks, with poetry, with language. Although I didn’t fully understand the poem for many years after that first read, the phrases I encountered became a part of my way of thinking. My arms, my heart, were water. I was free “with a ghastly freedom.”

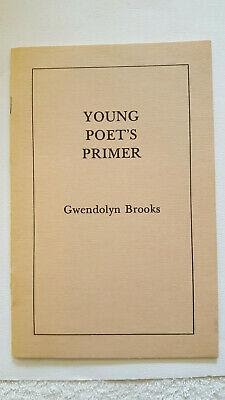

So, when Gwendolyn Brooks came to talk and read at a local Catholic school, I flew over there on my bicycle, hopeful, wide-eyed. After her talk, I stood in line to speak to her, to tell her that I, too, was a poet. And I did! She looked at me and smiled, then began rummaging around in her big purse. She pulled out a small pamphlet book titled “A Primer for Young Poets,” signed it and handed it to me. Thus Gwendolyn Brooks, herself, called me a poet.

So, when Gwendolyn Brooks came to talk and read at a local Catholic school, I flew over there on my bicycle, hopeful, wide-eyed. After her talk, I stood in line to speak to her, to tell her that I, too, was a poet. And I did! She looked at me and smiled, then began rummaging around in her big purse. She pulled out a small pamphlet book titled “A Primer for Young Poets,” signed it and handed it to me. Thus Gwendolyn Brooks, herself, called me a poet.

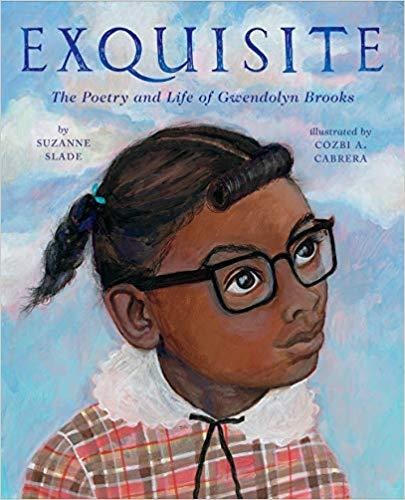

I have long since lost this treasure, probably because I loaned it to many other young poets over the years. But I have not lost this treasured memory nor my deep admiration for Brooks and many of the poets included in Peck’s anthology for young readers. It wasn’t until Suzanne Slade and Cozbi A. Cabrera’s book Exquisite: The Poetry and Life of Gwendolyn Brooks, that I realized I had never learned anything about her life. I didn’t know how she found poetry, how she developed her craft. I didn’t even know that she came from Chicago, just as my mother’s side of my family had. All I had were her poems, and that sweet gifted pamphlet.

This is one reason why I find biographical picturebooks (and biographies in general) so important and powerful. They provide an atlas, as Chris Meyers wrote, for where we might go in our lives and how we might get there. In Exquisite, I learned that Brooks grew up surrounded by books, that she began writing poems at age seven, that she persisted and wrote and wrote even though her writing never paid the bills. And then, one day, she won the Pulitzer Prize. The illustrations of young Gwendolyn, the timeline, the beaming photo in the backmatter, all this would have been of great significance to me as a young reader, providing a context that I didn’t know I needed, both to understand Brooks, but also to understand myself.

The following year, at fifteen, I was lucky to have an English teacher who assigned books that would become my favorite. I read Toni Morrison’s Beloved in that class, crushed and awed beneath the enormity and power of that story. I read A Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry, and I also read Fences by August Wilson. I didn’t realize I could enjoy reading a play, that my eyes wouldn’t get tired of the visual structure of the page. I didn’t realize that dialogue could carry so much emotion.

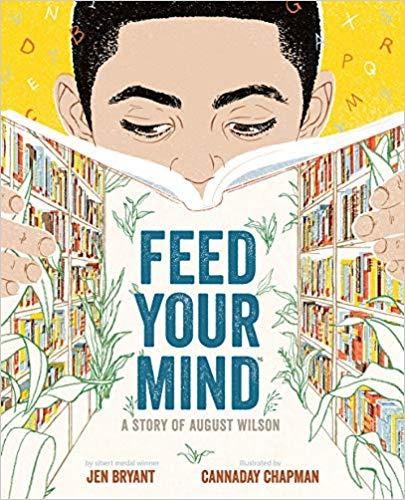

Feed Your Mind: A Story of August Wilson by Jen Bryant, illustrated by Cannaday Chapman, lets us watch Wilson grow up, also surrounded by books. Is that the secret to becoming a writer? If Wilson and Brooks marinated in a booky broth throughout their childhoods, only to become capable of such delicious wordplay, does that mean that reading might lead me down the same possible path? Through verse, Bryant describes Wilson’s delights, his literary mentors, but also the racism that pervades his experiences. Nothing can prevent him from writing. He is a poet before he is a playwright. As he grows into his adulthood, he grows into an accomplished writer, despite racism, despite rejection, despite being tired and busy, he is motivated and inspired. And he is an inspiration to me.

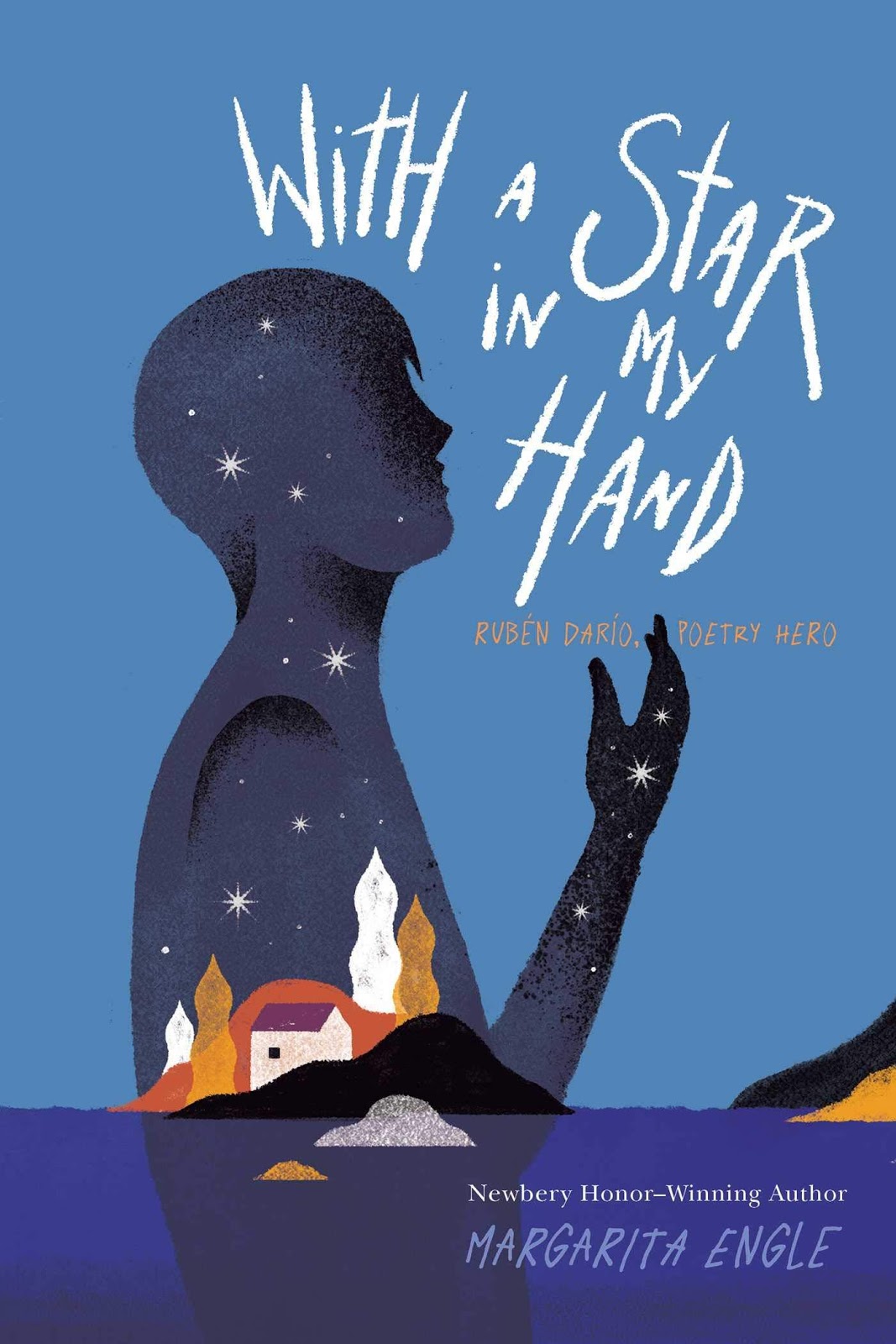

Although I want to focus solely on biographical picturebooks, I cannot help but mention With a Star in My Hand: Rubén Darío, Poetry Hero a biography in verse by Margarita Engle. When I received an advanced copy of this text, I recognized the name Rubén Darío, but it took me a few minutes to remember why. My youngest children’s school has a sister school in Nicaragua named after this beloved poet. His name is familiar to my children and their classmates, but not his story, so I was delighted when I learned that Engle’s newest book tells the story of Darío, the boy poet, as he was called, from Nicaragua, who became the father of Modernism. Enchanted by language from a very young age, writing poetry from the age of 3, Darío travelled the world writing poems against injustice, speaking out for the voiceless, language as his currency. He conjured his own poetic forms, dismantling and reforming poetic rules. Despite issues of alcoholism, despite being abandoned by his parents, despite financial insecurity, war and natural disasters, Rubén Darío continued to read and write, being an ambassador for poetry.

Although I want to focus solely on biographical picturebooks, I cannot help but mention With a Star in My Hand: Rubén Darío, Poetry Hero a biography in verse by Margarita Engle. When I received an advanced copy of this text, I recognized the name Rubén Darío, but it took me a few minutes to remember why. My youngest children’s school has a sister school in Nicaragua named after this beloved poet. His name is familiar to my children and their classmates, but not his story, so I was delighted when I learned that Engle’s newest book tells the story of Darío, the boy poet, as he was called, from Nicaragua, who became the father of Modernism. Enchanted by language from a very young age, writing poetry from the age of 3, Darío travelled the world writing poems against injustice, speaking out for the voiceless, language as his currency. He conjured his own poetic forms, dismantling and reforming poetic rules. Despite issues of alcoholism, despite being abandoned by his parents, despite financial insecurity, war and natural disasters, Rubén Darío continued to read and write, being an ambassador for poetry.

Many years ago, I asked Margarita Engle what she finds compelling about writing novels and biographies in verse, why she chooses to write in this style. She answered that narratives in verse leave more room for the child to place themselves and their own stories on the page, literally and figuratively. Thank you, writers of these lives, for offering readers such powerful and inspiring mentors. Sharing these life stories with children is one way to nourish a new generation of poets, playwrights, storytellers… literary artists.

Journey through Worlds of Words during our open reading hours: Monday-Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit its archival stream.

- Themes: Cannaday Chapman, Celeste Trimble, Cozbi A. Cabrera, Exquisite: The Poetry and Life of Gwendolyn Brooks, Feed Your Mind: A Story of August Wilson, Gwendolyn Brooks, Jen Bryant, Margarita Engle, Richard Peck, Sounds and Silences: Poetry For Now, Suzanne Slade, With a Star in My Hand: Rubén Darío Poetry Hero

- Descriptors: Books & Resources, WOW Currents