By Susan Corapi, Trinity International University, Deerfield, IL

The last fifteen months have been filled with science and math as we have followed the spread of a new virus and disease that rapidly shifted from localized outbreaks to a pandemic. We watched the race to develop mRNA and viral vector vaccines that were effective in protecting against COVID-19. We have been inundated with scientific diagrams, statistics, infection rates, and percentages of people vaccinated in different parts of the world–in other words, we have been immersed in principles of science and math. So, it seemed fitting to focus WOW Currents in July on global and multicultural books that engage with STEM subjects–science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. The titles this week portray scientists and mathematicians from around the world who have contributed to our understanding of their fields.

Cheryl Bardoe, in her biography of French mathematician Sophie Germain, quotes her as saying “The human spirit…requires more resources inside when outside it has less” (n.p.). Her words capture what it is like for many young adults interested in STEM content who are blocked from educational opportunities or from having their ideas seriously considered. The following biographies profile people who persevered, drawing on inner resources and often doing work below their capabilities while waiting for the chance to present their groundbreaking ideas.

Jeannine Atkins introduces readers to women in the STEM fields who often worked against limitations placed on them because of their gender. Grasping Mysteries: Girls Who Loved Math (2020) profiles seven women, some well-known, like astronomer Caroline Herschel, the first woman to discover a comet, and mathematician Katherine Johnson, one of NASA’s “hidden figures.” Another woman, Florence Nightingale, is well-known as one the pioneers of modern nursing, but not as well-known for her work in statistics that helped reform hospitals. A third group of women are less well-known. Geologist and cartographer Marie Tharp contributed toward mapping the floor of the Atlantic Ocean. Engineer Hertha Marks Ayerton studied electrical arcs and contributed insights in hydrodynamics by measuring ripples in the sand. Edna Lee Paisano was the first Native American demographer and statistician who worked for the US Census Bureau. By rephrasing the census questions, she improved the representation for minoritized populations. Finally, astronomer Vera Rubin found strong evidence for the existence of dark matter in the universe. Atkins tells the stories of these women through free verse, touching on both their scientific and mathematical contributions but also their personal lives and the inner reserves they drew on while waiting for the opportunity to work to their capacity.

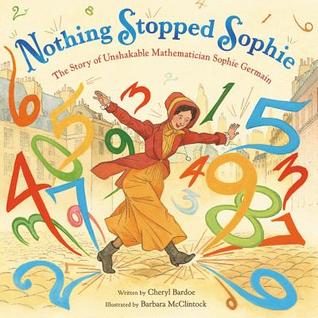

Cheryl Bardoe and Barbara McClintock introduce readers to an 18th century inquisitive and indomitable spirit in Nothing Stopped Sophie: The Story of Unshakable Mathematician Sophie Germain (2018). Sophie was born into a bourgeois family so was educated at home. Her thirst to know and understand principles of math helped her resist the parental pressure to read books appropriate for girls and instead study math books housed in her father’s library. Her zeal to ask questions and exchange mathematical thinking with others made her correspond with a male pen name. Like many women profiled in Atkins’ Grasping Mysteries, Germain’s research on vibrations and the elasticity of metals was groundbreaking but unacknowledged even when used later on to construct the Eiffel Tower, big bridges and skyscrapers.

This picturebook is a wonderful example of words and pictures working together to create the climate in which Germain lived. During the French Revolution many lost their heads to the guillotine. Sophie lived through four different kinds of governments in the first 19 years of her life and the order and consistency of math provided a safe zone when the world was in chaos around her. McClintock illustrates that contrast between chaos and order with fiery oversized numbers filling the streets along with people racing with torches while Sophie is engrossed in books, protected by house walls carved with numerical formulas and equations. In another double page spread, Sophie is surrounded by “gawkers in finery” admiring the math prodigy. Meanwhile Sophie is visually separated from party guests by a white cloud filled with formulas and equations demonstrating the little conversation that happened. Finally, when Sophie becomes the first woman to win a prize from the Royal Academy of Sciences, McClintock illustrates her impact by placing her on the steps of the Academy sending out a whirl of numbers and formulas that is blowing off hats and glasses and shaking up the Academy members. Because of Sophie’s persistence in exchanging ideas with other mathematicians, the idea that women can be capable thinkers was thickened.

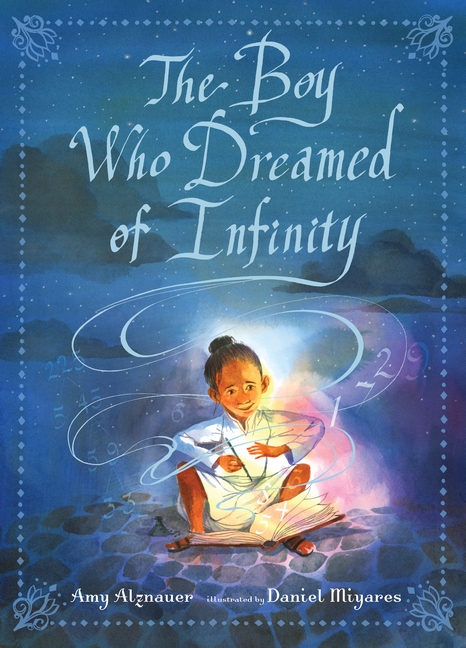

Srinivasa Ramanujan (1887-1920) did not face the gender-based limitations profiled so far, but he did face the limitations imposed by geography and poverty. He was born in the southernmost state in India to a clerk and his wife. Author Amy Alznauer explains in The Boy Who Dreamed of Infinity (2020) how geography limited the flow of ideas–even great and wonderful ideas–because of the slow means of communication and transportation. Alznauer and illustrator Daniel Miyares narrate the first two decades of Ramanujan’ life (he died at age 32), up to the time mathematician G. H. Hardy invited him to come to Cambridge.

Ramanujan was a genius participating in a school system that did not know how to encourage gifted thinkers so he often thought and studied on his own, recording his wonder, his questions and his ideas on whatever paper or surface he could find. They portray a young boy asking questions about big and small concepts. For example he wonders how a single entity like a mango can be repeatedly divided into smaller pieces, and consequently how sums (like 8+2) can be represented with smaller numbers (4+4+2), eventually only 1s (1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+1+).

The backstory to this picturebook is told in the Author’s Note and conveys the inner reserves that Ramanujan drew on when he was dismissed because of his race or status–the exuberant freedom and creativity he felt as he wondered, asked questions, and prayed. A devout Hindu, he believed that “I am small…God is big. I am trying to learn the thoughts of God” (n.p.). He described how the thoughts came to him in his dreams, landing on the tip of his tongue, and how he would write furiously to capture the idea before it disappeared. His ideas were so groundbreaking that they took number theory in new directions and are still being used today.

Cherokee author Traci Sorell and Metis illustrator Natasha Donovan narrate a story in which the limitation was gender, but the inner reserves Mary Ross drew on were the Cherokee values she had been raised with. Classified: The Secret Career of Mary Golda Ross, Cherokee Aerospace Engineer tells the story of how a young Native American woman kept studying when ostracized by the boys in her class because she had been taught to gain skills in all areas of life. When WWII begins, she was hired as an engineer by Lockheed to solve design problems for aircraft. Later, after the war, she was selected to be one of the members of the top-secret Skunk Works division to work on orbits and inter-planetary flight. Through her years at Lockheed, she exemplified the other values she had been taught: work cooperatively with others, remain humble when your talents are recognized, and ensure equal education and opportunity for all. She was instrumental in recruiting Native Americans and women to the engineering field.

Each of the people profiled were gifted in math or science, but more than that, they drew on inner strength to persevere in order to open up opportunities for themselves and others.

Next week: a look at environmental science!

Journey through Worlds of Words during our open reading hours: Monday-Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit its archival stream.

- Themes: Amy Alznauer, Barbara McClintock, Boy Who Dreamed of Infinity, Cheyrl Bardoe, Classified: The Secret Life of Mary Golda Ross, Daniel Miyares, Grasping Mysteries: Girls Who Loved Math, Jeannie Atkins, Natashi Donovan, Nothing Stopped Sophie, Susan Corapi, Traci Sorell

- Descriptors: Books & Resources, WOW Currents