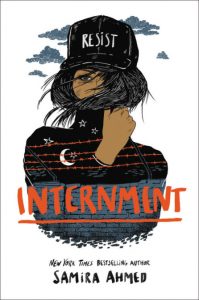

Book Review: Internment

Written by Samira Ahmed

Little, Brown, 2019, 387 pp

ISBN: 9780316522694

Layla Amin is an outspoken ordinary teen who shares the common concerns of any teen within the U.S.–teen crushes, grades, studies, parties, etc. That was before a U.S. president orders that Muslims be sent to internment/detention camps because of their faith. Layla’s father is a renowned author and professor at a reputable university and writes poems with an activist/progressive content. He loses his job and his books are burned. The detention camp where Layla and her family are sent is located in ‘Independence California.’ Camp Mobius is situated close to the site of an actual detention camp for Japanese Americans during WWII. This location is a deliberate decision by the author to connect the historical past with the present. The Director of the camp believes he is above the law in relation to the protection of U.S. citizens and so orders attacks on inhabitants and is deliberately cruel to women. Layla ends up taking action and organizing the teens in the camp to conduct demonstrations and demand being released from the camp. She manages to access the internet through her Jewish boyfriend on the outside and a guard on the inside. Her blog posts and videos go viral and result in a national uproar, which brings reporters and other people to the camp and Red Cross workers as observers. A group of Muslims within the camp are employed by the Director, and are referred to as ‘minders.’ They remain loyal to and side with the Director on how to keep the citizens of the camp “in order.” Some guards on the inside of the camp and Layla’s Jewish boyfriend on the outside provide support to the resistance. Although the novel is often grim, it ends with hope.

This book has already received a great deal of attention, including starred reviews from Booklist (2/01/19), Kirkus (1/01/19), Publishers Weekly (1/07/19), School Library Connection (3/01/19) and School Library Journal (3/01/19). Other reviews were published in the Bulletin of the Center for Children’s Books (2/01/19), Horn Book Magazine (3/01/19), and the New York Times (3/10/19).

The story launches with an unsettling beginning where Layla is blatantly trying to break curfew to meet her boyfriend. The novel is written in the first person with the heartfelt expressions of Layla’s feelings and thoughts. Apprehensive about her independent and deliberately provocative actions, her parents try to play it safe and curb her outbursts. Then the Exclusion Guards storm into their home to forcibly remove them from their beloved way of life. As the family and other camp members try to adjust to their new restricted surroundings, they are under constant surveillance by drones and guards and an electrically charged boundary. What they see through the wires is an open but inaccessible landscape. Whoever raises a voice disappears and no one knows where they go. A friend and a strong teen activist is lost to the electric wires that keep them inside the camp. The threat of the all-powerful Director looms but there is little emphasis on physical torture. Layla says about her new reality, “I don’t measure time by the old calendar anymore; I don’t look at the date. There is only Then and Now. There is only what we once were and what we have become.” (p. 2).

This narrative is strong and well written but makes the reader wonder about its acceptance for publication in the current political climate. The book is an alternate version of the present, but the underlying messages are relevant to today’s reality where the national and global conversations are often against immigration, with negative portrayals of Muslims. With the separation of families and their children in cages at the border with Mexico, this book can encourage conversations about a range of issues related to immigration and racism. The representation of good and bad in both communities is a strength of the narrative. The ‘minders’ who sell out other Muslims and the close group around the Director are presented as enablers of the situation, but these negative actions are balanced by the actions of some of the guards and Layla’s non-Muslim boyfriend. This narrative is considered a “near” dystopia that could happen in the near future and that connects to present U.S. events such as those of migrants coming from Central America, making the book an effective and courageous commentary on current events. As a reader, I do wonder if such a situation did arise whether the ending would be as hopeful and if the powerful guards would go against direct orders from higher up to help.

These deeply held negative views about Muslims are global and are increasing, with only a small number of supportive voices. Although hope comes from people outside the camp in the novel, the movement of resistance is initiated within the camp with the passionate voices of teens. What is concerning in the narrative is the attitudes of Layla’s parent’s generation, who are presented as complicit and accepting of the situation rather than supporting the youth. Oppression and displacement always result in this range of reactions. This can be seen currently in Muslim countries, where terrorist groups like ISIS have been able to use fear to take control and engage in terrorist acts that often hurt other Muslims and reinforce globally held negative stereotypes of Muslims.

Beneath this deeply unsettling fear is the realization that this novel is more realistic than dystopic, and that youth often lead the movement to ensure, or move towards, justice for all. When Layla decides to write about what is occurring in the camps, to tell the story that the Director of the camp and the Exclusion Authority is trying to keep from the U.S. public, she does so because it is necessary and despite all the risks. “I have to do something… we have to tell people. I don’t think people on the outside will tolerate this if they know” (p. 187). Her courage in the face of real threats from those in power, not only intimidations against her physical and emotional self but also against all that she loves, is an inspiration. This kind of leadership by youth taking action against injustice is not a new trope in YA or in real life, but speaks to the reader of this book in a particularly strong way due to the present political climate.

The fictional voice within this narrative holds so much significance, because it allows readers to imagine themselves speaking out and acting with courage in the face of oppression alongside the brave adolescents who are doing so in our world right now in response to climate change, gun violence and sexual abuse. The recent real-life events where the youth are standing up and speaking truth to power shows the power of the strength and will of the common people to bring down formidable organizations.

Other narratives thematically connected to this one are hard to locate, but one that stands out is Guantanamo Boy by Anna Perera (2011) about Khalid, an average fifteen-year-old boy in England who enjoys playing video games, hanging out with his friends, and cheering for his favorite soccer team. His father is from Pakistan and mother is from Turkey. He has visited Pakistan as an infant but has not been to Turkey. He goes through the same apprehensions and accolades as his friends except for the fact that he is a Muslim and, in the words of Khalid’s father, “these are bad times for Muslims.” The story is set soon after the events of 9/11. On a family trip to help his paternal aunts settle into a new home in Pakistan, he is kidnapped by the CIA and taken initially to a prison in Afghanistan and then later to the notorious Guantanamo Bay prison as a suspected terrorist. He endures all levels of physical and mental torture, including extreme psychological manipulation to the point that he suffers a mental collapse.

The author of Internment, Samira Ahmed, is a New York Times bestselling author of multiple books. She was born in Bombay, India but has been a long-time resident of the U.S., living outside of Chicago. She wrote this novel based on her experiences growing up in the U.S., weaving her experiences into this strong narrative. Find her online at https://samiraahmed.com/, https://twitter.com/@sam_aye_ahm and Instagram.

Seemi Aziz, University of Arizona