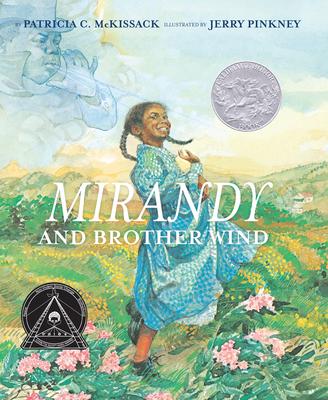

Mirandy and Brother Wind

Written by Patricia McKissack

Illustrated by Jerry Pinkney

Dragonfly Books, 1988, 32pp

ISBN: 978-0679883333

McKissack tells the story of Mirandy’s determination to win the junior cakewalk, a contest in which “walkers” are eliminated until the final couple wins the prize. To achieve her goal, Mirandy seeks help from her community. Mirandy’s friend Ezel, Ma Dear, Grandmama Beasley, Miss Poinsettia, and the mythical Brother Wind guide her on her journey to becoming the winner of her first cakewalk. Pinkney’s bright color scheme and realistic illustrations of the African American aesthetic emphasize the story’s optimistic tone and early twentieth century setting.

Mirandy and Brother Wind has supernatural and fantastical tones. McKissack introduces Brother Wind as “coming high steppin’, dressed in his finest and trailing that long, silvery wind cape behind him.” Pinkney’s illustrations depict Brother Wind as a flying, peculiar figure who has the features of an African American man yet has bluish-gray coloring. His sustained presence seems to have a magical effect as evidenced by Mirandy’s statement, “Sure wish Brother Wind could be my dance partner at the junior cakewalk. I’d be sure to win.” Ma Dear confirms his impact, “There’s an old saying that whoever catch the Wind can make him do their bidding.” Mirandy then goes to a conjure woman whom she hopes will help her catch the elusive Brother Wind. Brother Wind’s origin and the conjure woman’s methods are not developed. It can be argued that these developments are not relevant to the story; however, this absence brings up a point about genres in African American literature. Brooks and MacNair (2009), in their article on African American literature, point out that scholars see the need for increased African American characters in fantasy, and question if this lack is because fantasy is seen as harmful to Black characters. If this were expanded, Mirandy and Brother Wind could offer windows and doors into African American, particularly Southern, spirituality; nevertheless, this book’s depiction of early twentieth century African Americans is evocative. Other aspects of the book can offer the reader mirrors, windows, and doors (Bishop, 2010).

Botelho and Rudman (2009) state, “The analysis of the representation process shows that meaning does not come directly from words but instead is re/presented in language (written or visual)” (p. 2). Pinkney’s illustrations of African Americans gave me a mirror to think about my own features, complexion and hairstyles and that of my family. I saw myself represented. According to Sims (2010):

Pinkney’s approach involves the staging of scenes using models and photography. As a result, his characters always look like real, ordinary people. They are individualized and reflect the natural diversity of Black people. The history of Black imagery in children’s books, and the desire to affirm the beauty and worth of Black people make the portrayal of Black characters in children’s books an important consideration. (p. 233)

McKissack’s use of dialect such as gon’ instead of ‘going to’ and double negatives allowed me to affirm my speech patterns. However, usage of African American Vernacular English (AAVE) is not always viewed positively. Some African American readers may feel offended by the inclusion of AAVE in African American literature (Brooks & McNair, 2009). The dialect in this book, however, is a rich illustration of intracultural variations and shows the diversity that exists within cultures.

While reading this book, I received a window into early twentieth century African American culture. Mirandy and Brother Wind can be perceived as a mythical history lesson on bygone African American traditions, such as the cakewalk. According to McKissack’s (1988) note, “First introduced in America by slaves, the cakewalk is a dance rooted in Afro-American culture. It was performed by couples. The winning couple took home a cake.” This book sparked my curiosity as I was left with questions about cakewalks. In what African countries did cakewalks originate? Were slaves able to engage in cakewalks? Why did cakewalks fall out of popularity?

To explore supernatural and historical themes Mirandy and Brother Wind can be paired with Patricia McKissack’s and Brian Pinkney’s The Dark-Thirty: Southern Tales of the Supernatural (1992) and Robert San Souci’s and Brian Pinkney’s The Faithful Friend (1995). After reading the books students could write brief narratives involving those themes. Organizing a cakewalk would also be a rich experience for students.

Patricia McKissack authored numerous books about the African American experience, sometimes with her husband Fred, many of which won awards. Before becoming a writer, Patricia was a teacher and then editor of children’s books, both of which propelled her into writing. Read more about her at http://www.patriciamckissack.com/

Jerry Pinkney has been illustrating children’s books since 1964. He has won numerous awards for his work and also exhibits his art in museums. He considers himself a storyteller at heart which is what drew him to picturebooks. Jerry currently lives in New York. Read more about him at http://www.jerrypinkneystudio.com/

LaShanda Francis, University of Texas at Arlington

Works Cited

Bishop, R. (2011). African American’s children literature: Researching its development, exploring its voices. In S. A. Wolf, K. Coats, P. Enciso, & C. A. Jenkins, (eds.), Handbook of Research on Children’s and Young Adult Literature (pp. 225-236). Routledge.

Botelho, M.J. & Rudman, M.K. (2009). Critical multicultural analysis of children’s literature: Mirrors, windows, and doors. Routledge.

Brooks, W. & McNair, J.C. (2009). “But this story of mine is not unique”: A review of research on African American’s children literature. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 125-162. doi: 10.3102/0034654308324653

WOW Review, Volume XII, Issue 3 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/review/xiii-3/