Expanding Our World through Global Inquiries

by Mary Ann Conrad

Our group of language arts and social studies teachers, along with writer Nancy Bo Flood, met monthly to reinforce our commitment to promoting global awareness among our students, many of whom have not traveled far beyond their Navajo communities. We were a diverse assortment of young and old, Anglo and Navajo, all teachers under the same pressure to improve progress in our classrooms in an effort to bring up our school test scores.

Chinle Junior High is located in the heart of the Navajo Nation of Northern Arizona. Our students are 95% Navajo, and many have limited command of their own Navajo language and of English as well. Culturally, our students are engaged in rich oral stories that are told in the winter and passed down from generation to generation by those entrusted with them. Their struggles with English and with reading the written word have made passing standardized tests a major challenge for many of students. This challenge has been passed on to us, their teachers.

Teachers met weekly in cluster groups where we focused mostly on teaching academic vocabulary effectively. However, we gathered as a global literacy group at lunch every four weeks and discussed our commitment to global awareness. We decided on a slogan “Alike, yet Different” to describe our approach. In April we hosted a world reading night featuring books representing countries from each continent. Student Council members led attendees from continent to continent where they had their “passports” stamped as they explored the artifacts and local foods. At the same event Nancy Bo Flood signed copies of her new book Cowboy Up, which features the Navajo rodeo.

By the end of the school year, half of our group members had moved on. Chantell, one of our youngest teachers, decided to leave the teaching profession to join the Peace Corp. Before leaving, she taught three weeks of summer school with a focus on world geography and literature, saying, “This is the way teaching ought to be.”

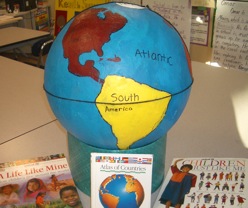

This vignette tells only part of our story and the impact of our focus on world literature. It begins in a special education classroom when 7th and 8th grade students came back fresh from winter break to find a large paper mache sphere in the center of the room. They were engaged before the bell even rang!  Just before the holidays, this teacher, an avid recycler, had been delighted upon walking into a math teacher’s room to find a large ancient globe split in two pieces and without a stand. With the vision of a world-class forager, she pounced. No more need to spend the holidays searching out a large balloon.

Just before the holidays, this teacher, an avid recycler, had been delighted upon walking into a math teacher’s room to find a large ancient globe split in two pieces and without a stand. With the vision of a world-class forager, she pounced. No more need to spend the holidays searching out a large balloon.

During the early weeks of January students in three different writing classes painted and labeled oceans and continents while searching their new atlases for information about each continent. While some painted, others began the covers of their individual World Books. These were eight teacher-created chapters of maps and cloze exercises and questions to assist students in reading the two major books purchased from UNICEF, A Life like Mine and Children Just like Me. Inside the cover were flags to color–Arizona, US, and the UN to remind them that citizenship which begins in the Navajo Nation expands in an ever widening circle. The blue flag of the United Nations hung just inside the door of the classroom.

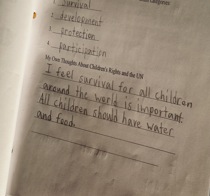

Emergent readers worked alone or in pairs to read about the United Nations and its concerns for children around the world. They wrote about the rights of children and about global issues, such as water and food resources, education, cultural belonging, and the need for peace and safety. They learned about food customs, clothing, possessions, values, and religious and family structures across the globe. They learned location. Every child they read about sent them to the political globes they hauled joyfully into the classroom when they arrived mid-January. They compared their lives and culture to the lives of children from other continents and countries.

This project continued throughout the semester, culminating in final student projects. Each student created his or her own personal double page spread modeled after the pages in Children Just like Me.

Other highlights of our world unit included reading about tooth customs around the world, learning about Celia Cruz and salsa dancing, and celebrating the Navajo rodeo with Nancy Bo Flood’s gift of a classroom set of books. One student pointed out where he sat, a tiny nearly invisible boy in the rodeo stands. It seemed right after “traveling” so far, to come home and find our places, our homes, our people and to celebrate them in the fresh way one always does after have been away.

References

Beeler, S. (1998) Throw your tooth on the roof: Tooth traditions from around the world. Illus G. B. Karas. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Brown, M. (2004). My name is Celia: The life of Celia Cruz. Illus. R. Lopez. Flagstaff, AZ: Northland.

Copsey, S. (1995) Children just like me. New York: Dorling Kindersley.

Leonard, S. (2002) A life like mine: How children live around the world. New York: Dorling Kindersley.

Mccloughlin, M. (2012). Seeds of generosity, Storytelling in the classroom. Victoria, BC: Salsbury House.

Smith, D. (2002) If the world were a village. Ill. S. Armstrong. Toronto: Kids Can Press.

Smith, D. (2011. This child, every child. Illus. S. Armstrong. Toronto: Kids Can Press.

Wright, D. & J. (2012). The world almanac children’s atlas. New York: Infobase.

Mary Ann Conrad is a special education language arts teacher at Chinle Junior High and facilitated the global literacy teacher study group.

WOW Stories, Volume IV, Issue 8 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/iv8.

The journey with Genny and her students has been one of the most powerful experience I ever had with books about Korea. Childhood connections became a powerful tool for children to wake up their curiosity to Korean culture and kids in Korea. Eventually this whole experience let them to think about critical stance of reading. Even though language was not all in English, childhood connection helped them to jump over the huddle in language barrier yet helped them to study carefully other visual cues like illustrations in the Korean picture books in return. This particular story Genny O’Herron wrote is empowering for me as a member of ACLIP indeed.

I can honestly say that I truly enjoyed reading this article. When I search for information on reading within the classroom, the majority of the articles are based around the elementary and middle school aged students. I really appreciate this in-depth discussion of how the teacher helped her students make connections and allowed them to follow the path that the book took them on. I teach at the ninth grade level in all co-teaching classes. My students are mostly not very inquisitive. I believe they have been taught all along to simply read and do the questions. We have lost a lot of the fun in teaching reading and learning about the information in the book. I a very inspired by this classroom and the functionality of the processing of the actual information within the text. We need to teach our students how make those connection and inquire into why things are the way they are. I have always loved to read and have never understand the disdain that many students have for reading. However, I know that if I can get them even slightly interested in the subject matter at hand, then the process is so much smoother. Once again, this was a fantastic article that I will be passing along to my colleagues.

Thanks, I agree that there are few examples of using global literature in secondary school classrooms and there is so much potential at that age level. May kids, however, have learned not to think in schools because not much has been asked of them beyond basic literal level thinking. So while they are capable of so much thinking, they also have a long instructional history of not thinking which we have to get beyond. The potential is there, though, as you point out.