When Literature Discussion Seems to Go Nowhere: Revaluing Teaching and Learning

by Lisa Thomas, Instructional Coach, Van Horne Elementary, A Vignette

Teachers at my school are inspired by the “grand conversations” described in articles about literature circles. Students in these articles seem to consistently think critically and collaboratively about important life issues. They appear to engage easily in dialogue and work together to create and uncover deeper meaning (Peterson & Eeds, 1990). We are wowed by the ways in which these children think about their world. Their conversations not only deepen children’s understanding of the literature, but through dialogue, they also better understand their lives and their world. We wanted children at our school to have the same experiences, so we began literature circles.

However, at the end of a long and challenging year exploring literature circles with third graders, our initial sense was that we hadn’t made much progress. Moments of brilliance didn’t come to mind as we tried to remember what was said and whether their talk about books had changed over time. Before allowing ourselves to become completely discouraged, we decided to look closely at our field notes and the children’s webs and literature responses to see if our classroom engagements had influenced the children’s talk in any way and to examine if there were missed opportunities where we could have more effectively supported their talk.

A Starting Point

I am the instructional coach at our school and teach collaboratively with the other teachers in the Learning Lab. The lab is a classroom where we explore teaching and learning. Participation in our lab experience is voluntary, but each teacher at our school has chosen to bring their students to the lab once a week. On Thursday afternoons the teachers and I meet with Kathy Short to study, reflect and collaborate about the lab experiences. We decided as a staff that we were interested in knowing more about literature circles and how they help children better understand themselves and the world. All of our study group and lab sessions for the fall focused on engaging children in meaningful talk about books.

We knew it was important to first determine what the children already knew about engaging talk about books. We wanted to see the kinds of thinking children were already doing and the ways in which they interacted with each other without our control or involvement. We selected a short story for this assessment because it would take less time to read aloud and give the group more time to talk. I suggested one of my favorite short stories. I had read it to many intermediate students and the response was always enthusiastic.

“A Mouthful” by Paul Jennings (1995) is the story of a young girl whose father loves to play practical jokes on his daughter’s friends. One of his favorites is placing pretend cat poo on the friend’s pillow. When it is discovered, the father disgusts the visitor by popping the pretend poo into his mouth. In the end, his daughter gets even by substituting real cat poo for the father’s fake one.

Each student helped themselves to paper and pencil as they entered our lab. I told them that I would pause a couple of times during the story to allow them to get their ideas down on paper. Then I introduced the idea of practical jokes and read the short story aloud. As predicted, their initial responses were emotional. Many were grossed out when they discovered that the father popped real poo into his mouth. They found the topic hilarious or bizarre and seemed surprised that we were reading about eating cat poo at school.

After reading the story aloud, pausing several times for them to write their thoughts, I told the third-graders that I wanted them to talk with each other about the story. I said that they didn’t need to raise their hands to talk—they could talk when no one else was talking. I let them know that the adults in the room would not be a part of the conversation. We would move away to listen and take notes. Then I joined the other teachers outside of the group and waited to see what would happen.

Several kids turned to a partner and began talking. Others waited. Then a few decided that, to establish order and/or for the sake of fairness, they needed to come up with some system for taking turns.

* Let’s do popcorn.

* We could just go around the circle.

* I think we should just talk. Who’s going to go first?

There was a brief sharing time. The comments were related to the story, but were not connected to what others were saying. Most simply read or told about what they had written on their papers. Many mentioned poo and fathers who play pranks. Soon they become frustrated with the lack of organization. Several complained about people talking when it wasn’t their turn. One child said, “This gives me a headache.”

We wanted to see if they could solve these challenges together, without our intervention. It was difficult, but we kept ourselves from stepping in. We knew that their previous second grade teacher had a “share chair” in their classroom. Students were invited to sit in the chair at the front of the room and present their work to the rest of class, who then celebrated with applause. One child proposed this structure but I told them that we wanted them to talk with each other, not present and applaud. It was very clear that they had less experience with the interactive nature of literature circles. They knew how to talk, but had less experience with listening to and building from one another. Certainly they didn’t yet have a vision of dialogue as thinking together in a struggle to understand significant issues within a book. They were not even at the point of having a conversation with each other; they took turns each making a comment and then considered their turn over.

Finally, I stepped in. “When you’re eating lunch in the cafeteria and having conversations with your friends, how do you know when it’s your turn to talk?” The kids had had plenty of experience talking to friends during lunch.

- Someone comes up with an idea, then we all listen and then talk.

- We just talk about things, but we don’t go in order.

- We just talk to one another.

I asked them to do a little research before our next time together. I wanted them to pay attention to their talk during lunch and see if they could come up with information that would help our conversations in class.

Upon reflection, it was clear to us that stories that entertain don’t necessarily support deep thought and discussion. Students had trouble remembering anything but the gross parts. I had intentionally introduced the concept of practical jokes as a sheltering strategy for students learning English, but this seemed to draw attention away from other big ideas within the text such as father/daughter relationships and embarrassment. Next time we would choose something less sensational and I would not introduce a particular frame.

We were aware that we should begin our journey by encouraging the children to pay attention to their personal connections. We needed a story that contained issues that were important to children—things they could relate to but, more importantly, mattered to them. It was the beginning of the school year and we didn’t know the children well enough to know yet what mattered to them. But, we knew from past experience with third graders that issues of friendship were significant to children this age and so looked for books about friendship.

Taking Turns to Share Personal Connections

For learning to take place, we need to make connections between new experiences and what we understand about our world (Short, 1993). Real meaning arises when readers are able to structure it themselves, to interpret ideas in light of personal experiences (Peterson & Eeds, 1990). We wanted children to attend to what they were experiencing within the text but we also wanted them to use their personal experiences to interpret the text as well as to use their experiences with the text to re-interpret their lives. We believed that being able to talk about the text in personal ways would help children explore the personal significance the text had for them as well as more critically engage in interpreting the text (Eeds & Wells, 1989).

At our next meeting I told the kids to pay attention to their thinking as they listened to the story. I especially wanted them to see if the story reminded them of anything that had happened to them—to pay attention to their personal connections. I read Best Friends (Kellogg, 1986). Afterward, we engaged in a quick write (2-3 minutes of independent writing) of our thinking about the book. After the quick write, the adults in the room demonstrated by sharing the connections they had made as they listened to the book.

When it was time to discuss, I reminded the kids that they didn’t need to raise their hands. They would know it was their turn to talk when no one else was talking. The kids connected easily to the story. Many told about their own pets. Some connected to the concept of friendship. Nathan shared sadly about a time that he beat a friend at Chicken Fights and how the other child got upset about losing and decided not to be his friend anymore. Another student said that the characters used their imagination just like she and her sister. They seemed more comfortable this time. They interrupted less and didn’t talk on top of each other quite as much. No one complained of headaches. Following our discussion, we created a web of the connections that were made.

We celebrated that the students connected to the story so easily. Many of their quick writes showed connections to the story—some showed multiple connections. We felt that we would need to support the children in connecting their personal stories back to the book. They took turns more easily, but didn’t build on the ideas of each other. Some still read directly from their quick writes, while others just talked about their ideas.

It was interesting to us that the children who seemed most comfortable with talking naturally about the book and their connections were not the students that the classroom teacher described as the “top” students academically. These were students who often struggled with reading and writing. Maybe listening instead of reading and speaking instead of writing freed their thinking. We thought that possibly those who tended to get top grades and score higher on tests were still trying to figure out what the teacher wanted them to say or what the right answer might be.

We felt that the next step would be to engage the children in small group discussions so that more children would have a chance to participate. We also decided to ask them to explain how their personal connections related back to the book. The children seemed drawn to the idea of struggles between friends and so we looked for a book that would help us explore this issue further.

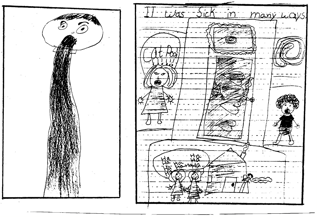

At the beginning of our next class, I introduced graffiti boards (Short & Harste, 1996) to the third graders. A graffiti board is a big sheet of paper that is shared by a group sitting at a table. Each person uses a corner of the board to write or sketch her thoughts in a random or “graffiti” like fashion. I told the children that after our story they would be moving to the tables to show their thinking using words or picture on the graffiti board.

I read You’re Not My Best Friend Anymore (Pomerantz, 1998). The students moved to the tables to show their thinking on the graffiti boards. When they got there, they immediately began talking about the story with the other children. We asked them to first get their ideas on the board—that they would have a chance to talk about them afterwards. The children were uncertain about what to do and how to share the paper. As we walked around we encouraged them to show more than one idea or connection on the board.

After a few minutes I asked them to turn and talk about the book at their tables. They finished talking quickly. Most went around the table in a sharing like fashion—each commented and then it was the next person’s turn. When we came back to the Story Floor, I asked them what they discussed at their tables and recorded their ideas on a web.

At first their personal connections were genuine—but some of the children began inventing connections, and the stories became increasingly sillier and more entertaining. The children seemed to be attempting to “one up” each another hoping for a bigger laugh. We wondered if they were doing this purely for entertainment purposes or because they didn’t feel that their real life stories were worth sharing. We also noticed that the children still seemed unclear about how to use a graffiti board and how to discuss. We decided that they probably needed to watch others use a board to figure out what to put on it and how to use their graffiti to support a discussion with each other.

Our decision to use Evan’s Corner (Hill, 1993) grew from the children’s interest in family conflict during this discussion. Evan’s Corner is the story of a young boy who shares a small home with his family. He dreams of having a space of his own, but as he creates this personal space in the corner of his house, he grows to understand that he’s lonely away from the others.

Before reading the story aloud, I invited the children to be researchers. I asked them to listen to and watch the adults as they responded to the book on a graffiti board. Afterward, we would work together to describe what we saw.

As I read the book, Mrs. Ford, Dr. Short, Mrs. Nichols and our principal, Mr. Overstreet, sat on the floor around an empty piece of chart paper and a collection of markers. They responded using words and pictures during the story and then talked about the book.

Following the discussion, I asked the kids to tell me what they noticed. I recorded their responses on a chart:

- They all wrote about connections to loneliness.

- They talked about the same thing—some listened.

- They recorded what they were thinking on the paper.

- When one person made a connection it helped the others to connect.

- They had similar connections.

- They waited in the beginning to write.

- Sometimes they paused to listen.

- They started sharing connections and then connected to the characters.

- One person shared, and the others talked about the same thing-built on it.

- When they stopped talking, they went on to a new idea.

- They didn’t take turns.

- Their graffiti are sketches.

The children identified the critical differences between the adult discussion and their own from the previous week. We wondered if this experience would make a difference in how the students engaged in literature circles next time.

The next week, we had the students gather at their tables. Each table had a blank piece of chart paper and some markers. We reminded them about their observations the week before and called their attention to a chart that listed a few of their ideas that we really felt they needed to focus on.

- Start with connections to the story.

- One person shares, then everyone talks about that idea.

- When that talk finishes, someone shares a new idea.

Mrs. Ford read Evan’s Corner again. The other adults joined a table and participated on the graffiti board along with the children. As she read aloud, everyone began showing their thinking on the graffiti boards using words and pictures. Then we asked the small groups to turn and talk. The role of the adults was primarily participant, crossing over to facilitator if necessary. Much of the talk at the tables was about personal connections to the pet or to sibling conflicts. Children noticed differences in their lives and the way that Evan lived, which made them think that the story was from “long ago”. One student was surprised that Evan’s parents let him go to the pet store by himself.

Afterwards, we gathered at the Story Floor and the children shared their perceptions of the conversations at the tables. The kids said that it was frustrating when someone said something and changed the whole subject. They also shared that some didn’t seem to have much to talk about; they finished quickly and then just sat.

We noticed that shifts seemed to be occurring in their talk. Children were becoming more comfortable with talking about their ideas instead of reading them from their quick writes and were attending to others better. Some of their connections seemed to be invented, but they were much more fluent in sharing those connections. For the most part, their connections were to details within the story. Evan had a pet, so did they. We wanted to push them to connect to the bigger ideas and issues and we wanted them to stay with an idea and work it through together. We noticed that when one child shared a connection, it didn’t necessarily cause others to build. It was simply a personal story—when it was over, nothing more needed to be said. When someone was confused or surprised by something in the story, the tension that existed caused others join in, attempting to help solve the puzzle or answer the question. We realized that we needed to add wonderings to the kinds of thinking we asked kids to pay particular attention to. We also needed a book that would allow children to further explore their interest in struggles with family and friends.

Sharing What We Wonder About

In thinking about a literature circle, we realized that if you don’t wonder about something, there is little to talk about and try to work out together. To have dialogue there has to be tension, and one way to get to tension is through wondering. Wondering about the issues addressed in stories is natural. We wanted children to pay attention to a way of thinking that we knew they were already doing.

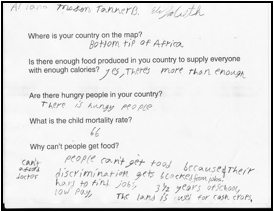

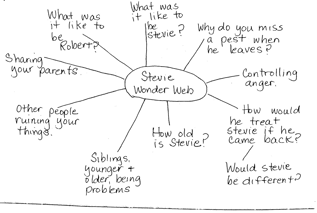

Stevie, by John Steptoe (1969), is a story of a boy’s resentment toward the younger boy that his mother babysits. In the end, Stevie moves away and Robert realizes that he misses having him around. Before I read the book, I introduced the response sheet that we would be using to gather our connections and wondering about the book. The sheet was a half piece of paper with spaces labeled “connections” and “wonderings.” I had completed one of the charts in response to Evan’s Corner to model its use for the children. I read Stevie to the children at the Story Floor, and then dismissed them to tables to reflect on their thinking on their response sheets.

After kids had time to get their ideas down, we asked them to turn and talk. At one table a student wondered if Robert’s mom missed Stevie’s mom and where Stevie moved to. Another wondered if Robert would have treated Stevie differently if he had been his brother or cousin. One child made a connection, sharing that his mom watched a kid who drove him crazy by getting into his things. Eventually the children moved into stories about big brothers and sisters.

When the children came back to the Story Floor, I asked them to share what they were still wondering about. One issue that immediately came up was why Robert’s mom didn’t do anything about Stevie doing bad things. The students explored different reasons for her behavior, including:

- It just wasn’t her personality.

- He was too little.

- She didn’t see him do it.

- He didn’t know the rules—maybe it was O.K. at his house.

- It might make him cry.

- Maybe she heard Robert being mean to Stevie.

It was the kind exchange we had been hoping for. Students were working together, using their experiences and understandings to make sense of issues in the story. They went on to question the change in Robert’s feelings and to wonder what might happen if Stevie came back. Several shared personal connections about being angry and how they acted.

Then I made a fatal error. I shared a connection about a time I had to share my mother with a child she watched. I told them about my anger and that I remembered wanting to bite the girl. What followed were biting stories. The group abandoned the book and began entertaining one anther again. I learned that a teacher’s role in discussion is fragile. While the children and I are working through our understanding of literature circles, I need to be careful about when and how I join in. I decided to lean away from talking and toward listening and taking field notes.

We were curious what the children thought about their talk and so I asked, “Which helped your discussion more—connections or wonderings?”

- Connections. I said a connection and others added theirs, like a chain reaction.

- Connections. We talked about fighting and not liking a person. We gave our opinions. There was one story and lots of opinions.

At first we were surprised by their responses. We had observed that their wonderings had created tensions that allowed them to sustain their talk. Then we realized that the children probably identified connections as being more helpful because connections were more personally significant to them. They may have felt that connections were more useful because they could tell one story after another, after another. Perhaps their responses showed that they were beginning to understand the value in talking for longer periods of time, but they didn’t yet see the need to talk longer about one idea in order to build new understanding together.

We wanted to help the children focus on an issue that mattered to them. Anger, pestering, and sibling relationships kept coming up and were certainly possibilities, but we also sensed that some children weren’t really interested in what others had to say. For them to engage in a meaningful conversation around any topic, they needed to understand that how they listened to and thought about the ideas of others was as important as the contributions they made themselves. Our focus wasn’t teaching them polite forms of interaction—we wanted them to experience how their thinking and understanding was expanded through interaction.

Listening to One Another

The real power in a conversation is in the mind of the listener. The words of the speaker matter less than the way in which you listen (or don’t listen as you plan what you are saying next). We wanted our students to see literature discussion as a way to explore problems rather than avoid them and to imagine alternative ways of thinking rather than dismiss them (Blau, 2003). We wanted them to come to know and value learning with and from others through dialogue. To do this, they would need to know how to listen in a way that would open their minds to new thoughts and understandings about the world.

We considered introducing language that would cause the children to connect to one another’s ideas. Phrases like “I agree/disagree,” “That makes me think about…” or “I want to add on to…” can give children the interim support that they need as they develop more natural habits of mind. But these phrases assume that listening is already occurring. If not, the phrases run the danger of becoming artificial transitions between isolated ideas. We felt that, at this point, we needed a structure that would give them a genuine reason to listen to one another.

The next week we broke into two groups. Our thinking was that each group would listen to a different but related story. They would have a brief discussion and then sketch or write about their thinking to prepare for sharing with a partner from the other group. The partners would talk about their stories and compare the two for ideas that connected both books. Then we’d come together and compare the stories.

We chose When Sophie Gets Angry, Really, Really Angry (Bang, 1999) and Angry Dragon (Robberecht, 2004) to build on the previous week’s discussion of anger. Mrs. Ford read one and I read the other. The students struggled a little when asked to talk about the story and so Mrs. Ford gave them a chance to sketch or write first. She noticed that this seemed to free their thoughts and they talked more easily afterwards. When the children met with a partner they did talk and listen more carefully. Some tried to compare without first telling each other the stories.

When we came back to the Story Floor we created a chart.

Similarities

About Anger

Both going somewhere using their feet

Both were not about being sad

Both got mad at someone in the family

Both wanted to hurt someone or something

Both had animals

Both had toys

Differences

1 boy/1 girl as characters

1 book about a dragon

1 about climbing a tree

1 mad about being told “no”

1 mad because sister took the gorilla

The animals were different

One played with toys, the other ate them

The kids talked and listened to one another more effectively, but clearly they were not addressing the big ideas. This structure gave them real reasons to listen to one another, but made it difficult for them to think together and build on one another’s ideas because they hadn’t heard the same story. We wondered about the talk in the small groups and whether the small groups were engaging more kids in talk. We decided to use the same structure, but this time look closely at the talk between the students in the small groups.

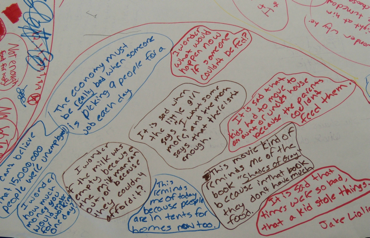

The stories that we chose were about anger between parents and children. Daddy is a Monster… Sometimes (Steptoe, 1983) and Harriet You Drive Me Wild (Fox, 2003). We had noticed that kids seemed to be particularly troubled by anger in interactions with adults and thought this might be tension to explore together.

After reading Daddy to half of the class, I asked students what they thought about the story. They began sharing a variety of connections, mostly about getting into trouble and fighting with siblings. They focused for a while on the illustration style in the book. They knew that illustrations convey important meaning and recognized that the drawings in the book weren’t simply stylistic. The angular outlines, patchy shading, and background patterns showed anger in ways that the words couldn’t.

- Why are the illustrations messed up?

- Why does he outline it all over?

- The illustrations look weird. It looks like it’s raining on the dad’s head when he’s mad. When he gets really angry, it’s raining fire.

- Let’s check the book to see if this is true every time he’s mad.

Then their attention was drawn to what they saw as an injustice in the story:

- It was mean that the dad laughed even though the lady gave them cones.

- Even though they got ice cream without permission, it was wrong to take the ice cream. And wrong to laugh. He was laughing at them, not with them. Bullying.

- My dad is nice to me. We have one room and he gave it to me.

- My dad yells at me and I’m not doing anything. He keeps changing his mind and telling us to turn the T.V. up or down.

We know that young children have a strong sense of right and wrong. They tend to see issues as oppositions. Many stories that children read and hear have clearly defined villains and heroes. The father in this book loved his children, but he didn’t always treat them with the patience and maturity that the third graders expected of parents. It was difficult for them to decide whether the father was a good or bad guy. This created a tension that fueled a genuine need to resolve their confusion. We also, for the first time, saw children make a personal connection that was focused on trying to figure out the book, rather than just sharing a related story.

We created another comparison chart for these books as a group, but these comparisons stayed on the surface and did not get into the issues we saw emerge in the small group.

Similarities

Both parents got mad at kids

Bother were about someone getting mad

Both had kids in them

Both have people, not animals

Both say sorry

Both feel bad

Differences

One had 2 kids and other had 1

One parent was a dad, 1 a mom

One was about a dad turning into a monster

Dad got mad about ice cream, mom got mad at all kinds of things

Mom tried to control her anger and dad just got mad every time

Mom got sad, dad didn’t

The injustice that the children felt in the way that the father treated the children in Daddy is a Monster… Sometimes certainly sparked a brief but focused conversation that fostered listening and group problem solving. At the same time, we knew that the children would be more likely to be able to sustain their talk and build on one another’s ideas if those ideas were bigger. We wondered whether having the children web what we knew about relationships would provide a broader conceptual framework to support their thinking and talk. We decided to follow this webbing with a book that is intentionally ambiguous—open to interpretation and debate. We wanted to create more tension.

When we met the next time, all of our previous read-aloud books were on the chalk rail and we asked children to brainstorm with us about the different ideas and issues related to relationships and how people treat one another that had come up in the books.

We then read aloud Fox (Wild, 2006), a fairly disturbing story about an injured bird who can’t fly and forms a symbiotic relationship with a dog who can’t see. A fox lures the bird away from the dog and leaves her to die saying, “Now you will know what it’s like to be truly alone.” In our adult discussion of this story it had provoked strong and uneasy attitudes and interpretations. We hoped it would spark tension and promote dialogue among Mrs. Ford’s third graders.

The children first discussed in small groups and then we gathered at the Story Floor. As they began to talk, students briefly shared personal connections to incidents in the book. Some said that the book made them feel lonely or sad. They were also intrigued by the illustration style and handwritten print and felt that the print made the book more upsetting and angry. But their talk quickly moved to their opinions about the characters and attempts to explain their behavior.

* Fox was mean. He wanted dog and bird never to see each other.

* I think fox really liked bird. He was jealous so he kidnapped her.

* He left her to teach her a lesson—sometimes you have to be lonely.

* Maybe he wanted to see if she could find the way back.

* Fox really wants to be friends with dog.

* No, he’s jealous of dog and wants to make him mad.

* Fox took the bird away from dog so that she could learn to make it without him.

It was interesting that many children didn’t view fox as evil and attempted to justify his behavior. Some explanations even sounded noble—to teach a lesson or help bird become stronger. Maybe they had a need to soften the story since the stories that they know tend to be kinder with happier endings. Perhaps they hadn’t experienced or didn’t recognize intentional meanness. Their search for the good in fox was unexpected and not at all the way the teachers felt about him when we discussed the story in study group.

The children’s talk was more focused and certainly more connected than we had seen previously. Although their thoughts about fox were broad and varied, they weren’t wild and random. Their attempts to explain his behavior were original, reasonable and grounded in their life experiences. Although they still tended to make comments rather than engage in discussion together, there were certainly “moments of brilliance” that we had overlooked until we looked closely at our notes from the literature circle.

Sustaining Talk around an Issue

It was time to move into a chapter book. The length and complexity of a longer story would not only give the children more to think and talk about, they would have more time to ponder and explore their ideas. We had been working with books about relationships and Mrs. Ford indicated that many students lived in less traditional family structures. We thought that Journey (MacLachlan, 1991) might invite students to talk about families and relationships in broad, meaningful ways. I introduced Journey in the lab and Mrs. Ford continued reading and engaging kids in discussion in their classroom. We created logs for the children’s response and taught them about sketch to stretch as a response strategy. Sketch to stretch focuses on symbolic meaning and involves creating a visual image of the meaning of the story, not an illustration of an event from the story.

Journey is the story of a brother and sister who are abandoned by their mother and are being raised by their grandparents. The younger brother, Journey, is angry about being left and believes his mother is coming back for him. After reading the first two chapters I asked the children what they were thinking. It made sense that their comments focused on what they were wondering about. They were clearly puzzled, in particular they were very concerned about why the mother left the children with their grandparents and were struggling with whether or not the mother would return.

- Maybe the mom will come back and Journey will be happy.

- It’s sort of sad. He doesn’t know where she is and why she went away.

- I wonder why the mom looks back?

- Maybe the mom will come back and then leave again and not come back.

- Why didn’t the mom leave a note for journey?

- Why did she give them money?

- Maybe she cared about them and wanted them to find her.

- Why did the mom leave and throw the jacket down?

- Maybe she had a job and needed to leave.

- She could have gone looking for the father.

- Maybe she got in trouble and didn’t want the family to know.

- “Your momma always wished to be someplace else.” Why does the grandfather say that?

- She wanted to kill herself.

- She dreamed of being someplace else—maybe she didn’t like where she was as a kid and so when she grew up she left.

- Maybe she got tired.

- She got bored of the children.

- She didn’t like doing things with the kids.

- Maybe she went some place she had always dreamed of.

- She went to get a break from everyone.

- A vacation day.

- Maybe she was depressed.

- She took a permanent vacation, doesn’t work there anymore. She left her job.

This was by far the longest exchange about one issue that we had observed with this class. We wondered what kinds of life experiences and previous texts the children pulled from in suggesting these possibilities. Looking at their talk now, we realize that for the first time, they used their life experiences to think through their interpretations of the story, not just to tell stories. Their comments weren’t judgmental like those toward the father in Monster and they didn’t try to rationalize the mother’s behavior as they had with Fox. They seemed to genuinely puzzle through the possibilities for why a mother might leave her family. They expressed hope that the mother would return but their hesitancy indicated that they were afraid that she would not and that this story might not end “happily ever after.” Interestingly, there was no acknowledgment during the discussion of Journey’s anger.

Over the next few weeks, they continued to listen and respond to Journey in their classroom and occasionally in the lab. They attempted to figure out the reasons for the characters’ actions in literature circles. They relied, as readers do, on their own life experiences to make sense of the character’s decisions. At times, these experiences added to their confusion. It made no sense that Journey’s sister would refuse money that her mother sent—Who would refuse money? They also struggled throughout with their hope that Journey’s mother would return and the realization that she probably wouldn’t. Initially, it appeared as though they didn’t want to voice this possibility out of fear that it might happen, but gradually the issue became part of their talk. Their tension over the mother’s actions and the children’s reactions to her abandonment became a sustaining issue that they continued to explore. While they were often tentative in their talk, for the first time they built upon their thinking with each other.

Revaluing Our Teaching and Student Learning

In the end, we were encouraged to see the children’s talk had grown over the year. Our initial impression that not much was accomplished probably stemmed from an unrealistic vision of literature circles with young children combined with our tendency to remember the students’ struggles better than their successes. We wondered whether the articles that had inspired our work highlighted students’ best work and so didn’t include the struggles and range of thinking that occur in any classroom.

The power that comes from the ability to revisit the work that we do as teachers was evident in our experience with these third graders. Our collection of student work and teacher field notes proved essential in our ability to determine our progress throughout the first semester. Without these artifacts, we would have been left with the false impression that growth hadn’t occurred. It’s tempting for us to draw conclusions based on our memories and sense of our experiences with children. The artifacts became evidence that informed our conclusions in more objective and concrete ways.

We remain committed to literature circles and our third graders will return to us next year as fourth graders. The time that we have taken to study the artifacts of student responses and to think critically about children’s understandings and the ways in which our teaching influenced their interactions will inform our curricular decisions. We will continue to support these children in using their connections and wonderings to think about literature and their lives. We will search for books that create in students the tensions that encourage dialogue. And as teachers, we will continue to collect and reflect together, allowing our students’ responses to guide our decisions.

Resources

Bang, M. (1999). When Sophie gets angry, really, really angry. New York: Scholastic.

Blau, S. (2003). The literature workshop. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Eeds, M. & Wells, M. (1989). Grand conversations: An exploration of meaning construction in literature study groups. Research in the Teaching of English, 23, 4-29.

Fox, M. (2003). Harriet, you’ll drive me wild! New York: Voyager.

Hill, E. S. (1993). Evan’s corner. New York: Puffin.

Jennings, P. (1995). A mouthful. Uncovered. (pp. 47-51). New York: Puffin.

Kellogg, S. (1986). Best friends. New York: Dial.

McLachlan, P. (1991). Journey. New York: Dell.

Peterson, R. & Eeds, M. (1990). Grand conversations: Literature groups in action. New York: Scholastic.

Pomeranz, C. (1998). You’re not my best friend anymore. New York: Dial.

Robberecht, T. (1999). Angry dragon. New York: Clarion.

Short, K. (1993). Literature as a way of knowing. York, ME: Stenhouse.

Short, K. & Harste, J. (1996). Creating classroom for authors and inquirers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Steptoe, J. (1983). Daddy is a monster…sometimes. New York: Trophy.

Steptoe, J. (1969). Stevie. New York: Harper.

Wild, M. (2006). Fox. LaJolla, CA: Kane/Miller.

WOW Stories, Volume I, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesi1/.