Belizean Voices: Reflection, Consideration, and Response

Sue Christian Parsons with Erica Aguilar, Melissa Bradley, Yvonne Howell, Ray Lawrence, Rashid Murillo, Guadencio Muxul, Denise Neal, Ruth Reneau, Tanesha Ross, and Gwendolyn Usher

The Belize Global Literacy Community is indeed a global community. All participants are associated with Oklahoma State University (OSU), but only one participant, the convener (Sue), actually joined from Oklahoma as a literacy education professor. The rest are educators in varied settings in Belize, some working in Belizean Ministry of Education positions supporting teachers in school and others teaching learners from early childhood to college. These Belizean educators are part of a doctoral cohort in the Language, Literacy, and Culture Ph.D. program at OSU. We met every other week through Zoom and continued our explorations and conversations digitally during other weeks.

As we explored the Worlds of Words Padlet and discussed our participation in the project, we noted that our stance seemed a bit different from other participating groups. We, too, were exploring global literature but with a view from a different part of the globe than many other participants. The Belizean participants, most working in contexts with limited access to real books for teaching, wanted to learn more about what books were available and how to use literature effectively in their classrooms. The U.S.-based participant, with broad knowledge of and access to trade books but limited understanding of Belizean teaching contexts, culture, and literature, wanted to expand her understanding of global contexts and perspectives. Though interested in exploring a broad range of global perspectives, we entered the work with a consideration of how books would resound with Belizean readers in Belizean classrooms.

We read scholarly work to ground and guide our exploration. In response to Sims Bishop’s (1990) timeless essay, Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Glass Doors, we discussed the challenge of finding texts in which Belizean children could see themselves. As we talked, our conversations focused on limited access to books and the lack of representation of Belizean voices in their curated curriculum and textbooks.

- In the school system in Belize, students rarely experience content that mirrors them. They are often exposed to windows and sliding doors that allow them to peer into the lives of foreign principles and belief systems. Thus, there is some disadvantage to individuals being bombarded with foreign doctrine. In some cases, this sets the stage for ideologies of superior culture to be implanted in the minds of minority groups. Readers are often poisoned with this view that they are inferior to the dominant principles highlighted in texts. While it is important for readers to learn about other people and places, it is even more vital that they learn about themselves. There needs to be more books that mirror the lives of minority and Indigenous groups. (Melissa)

- It is difficult to talk about global literature without first setting the stage to understanding what drives educational reforms in Belize. Belizean leaders and educators have a strong tie to the Caribbean; we use a lot of Caribbean written textbooks, novels, and children literature—along with American texts. This means that our rainbow of cultures is not depicted in the excerpts, short stories, or essays in these educational books. We need to move from politics and “strong emotional ties” to what is the reality in Belize and let’s help our own students see themselves in books. In chapter two,”Making sense of pedagogy” in the book Understanding Pedagogy Developing a Critical Approach to Teaching and Learning, Waring and Evans (2015) explore and explain the complex concept of pedagogy for axiological emancipatory interests. They echo educators must understand how pedagogy, at an organic level, informs instructors on how to view their positions as professionals of today and tomorrow. Educators should be consciously and actively engaged in “what and how are future learners’ interests being acknowledged and addressed in the curricula and schooling” (p. 26).

Pedagogy is a critical act of inquiry by the teacher to promote student learning. They rightly observe that pedagogy “is certainly not a neutral landscape—it is very much about a socially critical agenda, one in which notions of learner empowerment are framed by those power relationships that revolve around how knowledge is conceptualized and therefore what knowledge is valued, and how learners are positioned in relation to how that knowledge is created as part of the pedagogical process” (p. 28). I love this quote, it has me cathartic, it reminds me of the novels I read during my secondary education—none reflected my culture. I suspected it, felt ignored, voiceless, and on the brink of voice erasure if I had quit school. Many days, I felt as if I did not belong in school. I wanted to learn, but I also wanted to belong. (Erica)

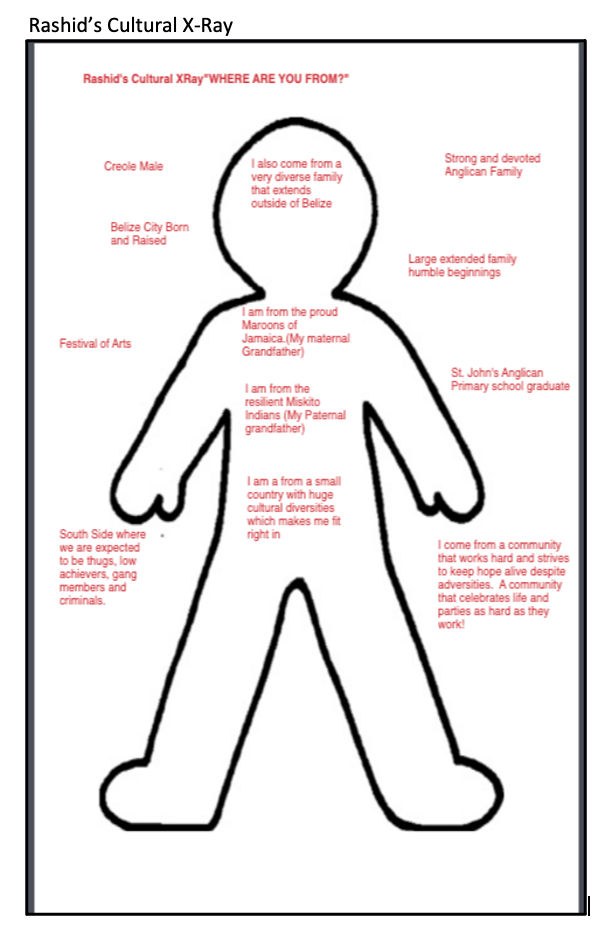

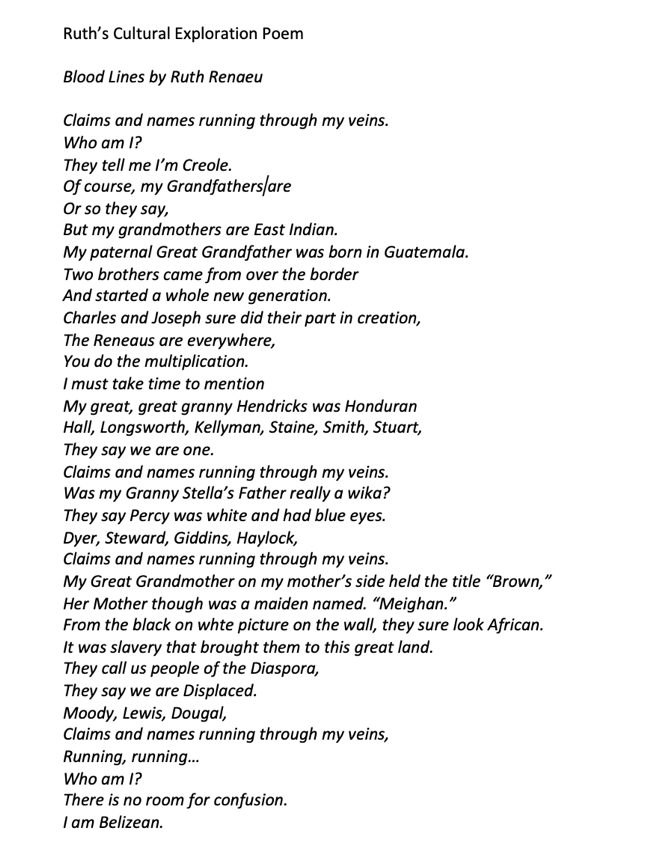

In response to Short’s (2009) framework for engaging with international literature, we began with exploring and sharing our own cultural identities through journey maps and cultural x-rays (Figure 1), a process that launched storytelling, poetry, and art (Figure 2), and helped develop a stronger sense of community, especially across the Belize/U.S. divide. We paired Short’s curricular framework with Leland, Lewison, and Harste’s (2018) similar framework for engaging learners in critical literacy through literature. As our work centered on Belizean voices and agency, we reached back to previous readings in Freire (1970) and explored pedagogical implication of critical literacy with Lewison, Flint, and Van Sluys (2002). Wolf (2009), Peterson and Eeds (2007), and Parsons et al. (2011) were also instrumental in exploring ways to center literature in the curriculum and engage readers in critical, authentic, and agentic literacy.

We searched for trade books, exploring resources that promised global perspectives and authorship such as the Outstanding International Books list published each year by the United States Board on Books for Young People. Because of the lack of representation of Belizean voices in the books we found, our selections offered cross-cultural inquiry. Our goal was to read books together, respond as readers in dialogue, consider books that would work well in Belizean classrooms, and explore pedagogical possibilities for engaging with those texts. As a children’s literature professor with resources available, Sue, the U.S. participant, worked on access, purchasing books for the group with Global Literacy Community award funding and additional funding sources. We began with novels, a list of books representing various global perspectives. Participants explored the books to find those that seemed most interesting to them and, potentially, to their students. From a broad initial list, we chose four with the intent of having small group literature study sessions: Children of Blood and Bone (Adeyemi, 2018), The Other Half of Happy (Balcácel, 2019), Hurricane Child (Callender, 2018), and A Time to Dance (Venkatraman, 2014). For quick access, we planned to purchase digital copies of the books only to find that accessing the purchased books on the Belizean end was difficult. Computer after computer flashed with the message that this book was not available to users in Belize. We contacted Amazon in hopes of using their global distributors, but Belize was not one of the options for shipping. Though we eventually found workarounds for digital book access, the struggle highlighted barriers to sharing global literature.

While we waited for novel access, we explored a wide range of picturebooks. We worked around access issues by sharing read alouds in our Zoom sessions and selecting quality books from the Epic Digital Library. We approached books as readers before we considered them as teachers. Though the books directly addressed cultural experiences beyond Belize, these conversations did much to illuminate content and themes that connected in meaningful ways to Belizean experiences. The group gravitated to books that explored diverse heritages in a diverse society and the importance of being seen and valued, as well as celebrated heritage and community. Books that acknowledged colonialism, a strong thread in the tapestry of Belizean cultural history and current realities resounded as did books that celebrated the love of family. A strong sense of story was also a big point of appeal.

Throughout our time together, participants contributed their own creative as well as scholarly writing to the Padlet. As the work went on, we added a column expressly for Belizean voices to which participants added their own writing and writing from Belizean authors. Some books that were particularly meaningful to the group included: Auntie Luce’s Talking Paintings (Latour, 2018), I Am Every Good Thing (Barnes, 2020), Saturday (Mora, 2019), Digging for Words: José Alberto Guitérriez and the Library He Built (Kunkel, 2020), and Just a Minute: A Trickster Tale and Counting Book (Morales, 2016).

Auntie Luce’s Talking Paintings was a strong draw, not only for the Caribbean setting but because of the explicit attention to the enduring effects of colonialism. In response, the rich history of Belize came into conversation, a history marked heavily by colonial forces and a current culture shaped in many ways by those influences. This theme emerged again and again in responses to literature and exploration of literacy practices, especially in conversations about the novels that, in portraying diverse global experiences, invited conversations about participant’s own cultural heritages and histories.

Barnes’s and Mora’s books elicited an enthusiastic response as readers reveled in representation of individuals with African heritage, strong mirrors to many of them, their families, and their students. Discussion delved into comparisons of experiences of Black people in the U.S. and in Belize, noting similarities in history but also differences in social treatment. Also noted was gender representations of Black girls and the portrayals of their lived experiences. The mother/daughter adventures in Saturday rang true to many readers who noted the easy pace, the warm relationship, and the focus on positive resilience as feeling very much like the culture they live. Ruth noted with particular appreciation the focus on lives of women of African heritage, including a rare depiction of hair care.

Digging for Words elicited similar response and enthusiastic recognition of the lives of many Belizean students. Guadencio, in particular, recognized his Belizean community in this book set in Columbia and noted the power of such a book to speak across cultures.

- Students at the elementary level, in Orange Walk District, Belize, speak three languages which are Spanish, Creole and the English Language. Most students in a class would be from the mestizo culture just like in the story. The majority of students are also from the rural areas of Belize where they enjoy the maximum beauty of nature…similar to the neighborhood that is portrayed in the story. Something, very important that would relate the students to the story is the fact that most people in these villages work in hard labor or in the farms. Waking up early is nothing strange for these learners and going around in a truck like Don Jose is very familiar to [them]. With all the previously mentioned points, it is clear that the reader can easily bring this text to life and immerse [in the] lived experience of the main characters. This is a way of opening the world for learners through literature (Short, 2009). The familiarity of cultural aspects in the life of the characters in the writing allows readers to experience a new culture that they can easily embrace. When students recognize the cultures that influence their thinking, they become more aware of how and why culture is important to others. They no longer see culture as about the “other” and as exotic but recognize that it is at the heart of defining who they are as human beings (Short, 2009). It allows them to appreciate and respect other people and to acknowledge that we are one people sharing this world that we call home. (Guadencio)

Yvonne highlighted Just a Minute: A Trickster Tale and Counting Book as a book that is expressly and joyfully culturally specific. She sees a need for a wide collection of such books, representing varied cultural traditions within Belize, as a way to maintain the “uniqueness of many cultures” that may otherwise be lost in the common rhetoric of Belize as a “melting pot.”

The novels we chose represented a variety of cultural locations—West Africa, India, United States/Guatemala, and St. Thomas, Virgin Islands. Just as with the picturebooks, we came to the reading and dialogue first as readers and then reflected on the experiences as teachers considering possibilities for the classroom. We used the two-session literature study group structure suggested in Parsons et al. (2011). Short (2009) asserts that cross-cultural studies operate both as mirrors and windows (Sims-Bishop, 1990). As we engaged in dialogue about each text, reader’s own cultural identities informed our transactions. As a result, the rich multicultural tapestry of Belize emerged. Children of Blood and Bone elicited histories of minoritized communities who, having moved into Belize, also experienced cultural suppression. In response to A Time to Dance, one participant detailed her Indian heritage and the existence of an Indian community in Belize. The exploration of bicultural identity in The Other Half of Happy brought conversation focused on the value of multicultural perspectives in Belize and the importance of nurturing that multiplicity as national identity, while Hurricane Child raised discussion of gender positions and expectations, including a cultural struggle to understand and embrace members of the LGBTQ+ community.

- After reading Children of Blood and Bone, I certainly endorse Short’s (2009) statement that literature is a portal to gaining perspectives about other cultures and even finding commonality in our human existence. Though magical and mystical in foundation, it clearly depicts the desire to preserve cultural traditions and practices and highlights the power in cultural identity. Additionally, it illuminated the need to appreciate other cultural orientations and perspectives and “reading the world” from a critical perspective. (Ray)

In April, we had the opportunity to host author Daniel Nayeri who talked with us and others in the OSU community about his Printz Award winning book, Everything Sad is Untrue: A True Story. This immigrant narrative spoke to the Belizean educators as they continued to consider deeply what it means to teach in a strongly multicultural community. They noted the powerful immigrant stories that run through their communities and considered ways to make space for everyone’s stories to be heard through the books students read.

The initial instructional plan was to use the books and teaching practices (e.g., dialogue as pedagogy, transmediation of text, interpretive stances, readers as writers) in the teachers’ classrooms around Belize, conducting action research. Teachers would select the books they wanted for their classrooms. These books would be purchased with project funds and shipped to Belize. Several factors squelched those plans. First, for most of our time together, Belize was “shut down” due to the pandemic. Teachers were trying to work with distance learning but limited infrastructure and the lack of resources available to learners at home made conducting our research unfeasible. Additionally, the difficulty with access slowed our progress. We figured out workarounds for digital access, but those processes were still cumbersome and digital books were not the best option for classroom use. Shipping books directly to Belize from distributors proved problematic as well as the easier route of working with one publisher or distribution house, an avenue that wouldn’t lead to the wide range of representations we were seeking. Additionally, shipments into Belize from the U.S. involved a fee to be paid by the recipient at pick-up, a cost not easily absorbed by the participants. Eventually, we were granted dispensation of customs fees and taxes for one shipment of books. Sue purchased all books through award funds, added books donated by Daniel Nayeri, and sent one huge shipment to Belize for teachers to use in the fall.

As a learning community, we considered what new action work would best serve our purposes for this project and decided on two areas of focus. First, we would reflect upon our changing stances as teachers as a result of engagement with multicultural literature. Second, teachers felt the need to amplify Belizean voices we had found to be so marginalized in the literature accessible to us. Some examples of this culminating work are included below.

Our takeaways? Of central importance to Belizean educators was teaching for justice by prioritizing the experiences and voices of the members of their communities, including representation of and through languages and heritage.

- In terms of pedagogy, teaching the way we were taught did not make me feel alive, so why would I teach my students that way? It is time for an educational reform in Belize where the foundation is linguistic justice to promote social justice. After all, hasn’t it been said that literacy is about power and change—the power to change? Literacy in Belize has long been used as power to suppress change and cultural wealth. We must not stop at the teaching of reading and writing at the surface level, but continue to illustrate how these readings of novels, short stories, textbooks humanize certain people and how it does not to others—especially to our own Belizean people. (Erica)

Such work involves promoting Belizean voices and perspectives in classroom teaching, including learners and teachers as writers, examining cross-cultural texts critically with an eye toward relevance for Belizean readers, and intentionally adopting practices that encourage readers to read with awareness of how books position them as culturally-situated readers in a global community.

- Teachers can access books written by authors from across borders they know have some similarities to that of students and allow students to read, critically exploring and making connections through these similarities, prompting curiosity in finding about the differences. An example is Belizean classrooms have a large number of students whose parents are Central American immigrants. These students would be able to relate and make connections to the story, The Other Half of Happy written by Rebecca Belcarcel (2019). There are other books which reflect life after colonialism. Since Belize was a colony of Britain, these books would help the students understand who they are as a member of the Belizean society, through the reading of literature based in countries with similar historical backgrounds.

(Gwendolyn)

- As I reflect on my elementary school literacy experience, I can recall how much I disliked reading. The books I interacted with were not fun to read. However, I can remember my mother making a conscious effort to provide books to help develop literacy and numeracy concepts. The books that I read for pleasure were foreign books like The Three Little Pigs, Goldilocks and the Three Bears, and Rumpelstiltskin. None of those stories were a reflection of who I was and did not fit into my reality. As I entered into my secondary education journey, literature became more difficult. I read books that I was not interested in and studied text with designed questions. As a student, I could not relate to these stories, which made reading painful. As a primary school educator, I wanted to ensure that students did not have the same negative experience. So I ventured on a quest to investigate how to use literature to empower students. Providing students with choices about the books they read is a great motivation. Creating the learning space where they get to select books that informs them about other culture and seeing a reflection of themselves is vital. Students need books that serve as both mirrors and windows. According to Short (2009), exposing students to diverse books as they look at the world and reflect on themselves is the beginning of a deeper understanding of the world. Therefore, creating classroom libraries filled with diverse books that the teacher carefully selects will impact students’ reading experience. (Denise)

Educators viewed practices that give students voice and agency as paramount. Many noted the importance of providing choice in readings. Others noted the important shift from students answering questions about a text to teaching them from an early age to analyze and question the text. Dialogue proved instrumental in illuminating both text and reader in our work together, and teachers noted intent work toward teaching readers to engage in productive talk about texts to illuminate varied perspectives. They also saw great power in the arts as a tool to develop personal and culturally responsive understandings as well as to engage with texts well beyond the surface.

- I have come to learn that the issues my students were having with proper engagement with their texts emerged because of our use of culturally irrelevant texts. Students were not able to relate to or identify with these texts as they were culturally removed and alienated from the experiences within these texts…My hope is to inspire young Belizean writers to explore their cultural wealth through the creation of young adult literature from their cultural perspectives. Young adult literature and particularly picture books by Belizean authors or depicting Belizean cultural diversity is almost non-existent. This teaching transition provides the context and framework towards young Belizean literature production. (Ray)

- As a literacy scholar I no longer see labels, I see books as a journey to self-affirmation, respect, and appreciation for others. I see books as a powerful tool to foster critical thinking and promote social justice. I am now passionate about creating a forum for children to become readers…who understand and value what they read as they transact with text. The readings on critical literacy suggest that this concept is only fully achieved if it evokes change. This change will come if teachers factor in students’ cultural background and make the pedagogies contextually relevant. We should be creating lessons that are relevant to their reality and the world they live in…A goal of mine is to encourage teachers to create activities where students interact with each other, use music, art and drama to cater to a variety of learner needs. This is important for all subjects because it is through language and how students interact with each other that students truly learn. As I assume my role as a literacy scholar and administrator, I plan to create a digital space where students can connect to their identities, language practices and culture. I want my young adult learners to voice their opinions whilst respecting the opinion of others. (Tanesha)

Of utmost importance to the Belizean participants is sharing Belizean voices with the broader cultural community. Several already write texts for their learners to read and are actively considering seeking publication. They also posted about works by Belizean authors that they feel members of this broader community of seekers should know. One frequently mentioned is Beka Lamb (Edgell, 1982), the work of a Belizean-born author and set in Belize with authentic characters and contest. Others answered the call for Belizean writing by sharing their own work—the beginning drafts of a picturebook, a short story, books and other works by local authors available through the Belize National Library service. Participants shared the writing of their students as well, fresh voices from Belize, exploring what it means to be Belizean.

From the convener’s (Sue’s) standpoint, exploring multicultural literature with a community of educators shed light on the privilege of access and deepened her own understanding of a culture previously only viewed from the outside. The experience was humbling in the best way, a chance to sit back, listen and learn and, thus, reconsider and vet her own understandings and practices in selecting and engaging with global literature. Exploring culturally responsive literature practice in an international partnership was particularly rewarding. These explorations evoked not only experimentation with and adjustments to practice in all instructional contexts represented (early childhood to higher education), but also prompted deep and generative consideration of how instructional practices aimed at increasing literacy may instead actually silence voices and constrain learning—and of the power of international children’s literature to influence critical and joyful change.

References

Bishop, R.S. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom, 6(3). Retrieved from https://www.readingrockets.org/sites/default/files/Mirrors-Windows-and-Sliding-Glass-Doors.pdf.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum.

Leland, C., Lewison, M., & Harste, J. (2018). Teaching children’s literature: It’s critical! (2nd edition). Routledge.

Lewison, M., Flint, A.S., & Van Sluys, K. (2002). Taking on critical literacy: The journey of newcomers and novices. Language Arts, 79 (5).

Parsons, S.C., Mokhtari, K., Yellin, D. & Orwig, R. (2011). Literature study groups: Literacy learning “with legs.” Middle School Journal, 42(5).

Peterson, R. &. Eeds, M. (2001). Grand conversations: Literature study groups in action. Scholastic.

Short, K. (2009). Critically reading the word and the world: Building international understanding through literature. Bookbird: A Journal of International Children’s Literature. 47(2), 1-10.

Waring, M. & Evans, C. (2015). Understanding pedagogy: Developing a critical approach to teaching and learning. Routledge.

Wolf, S. (2003). Interpreting literature with children. Routledge

Children’s Literature Cited

Adeyemi, T. (2018). Children of blood and bone (Legacy of Orisha, 1). Holt.

Balcárcel, R. (2019). The other half of happy. Chronicle.

Barnes, D. (2020). I am every good thing (G.C. James, Illus.). Nancy Paulsen.

Callender, K. (2019). Hurricane child. Scholastic.

Kunkel, A.B. (2020). Digging for words: José Alberto Guitérriez and the library he built (P. Escobar, Illus.). Schwartz & Wade.

Latour, F. (2018). Auntie Luce’s talking paintings. (K. Daley, Illus.). Groundwood.

Mora, O. (2019). Saturday (O. Mora, Illus.). Little Brown.

Morales, Y. (2016). Just a minute: A trickster tale and counting book. (Y. Morales, Illus.). Chronicle.

Nayeri, D. (2020). Everything sad is untrue: A true story. Levine Querido.

Venkatraman, P. (2015). A time to dance. Penguin.

Sue Christian Parsons is an Associate Professor and the Jacques Munroe Professor of Reading and Literacy at Oklahoma State University.

WOW Stories, Volume X, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on work by Sue Christian Parsons with Erica Aguilar, Melissa Bradley, Yvonne Howell, Ray Lawrence, Rashid Murillo, Guadencio Muxul, Denise Neal, Ruth Reneau, Tanesha Ross, and Gwendolyn Usher at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/volume-x-issue-1/5/.

WOW stories: connections from the classroom

ISSN 2577-0551