Learning About the Olympics: An Integrated Curriculum and Multi-Class Celebration

Cassandra Sutherland and Lacey Elisea

We are educators at Creation School, a private Lutheran school located in Vail, Arizona, a small community approximately 20 miles southeast of Tucson. Creation School is developing a curriculum using global literature. This curriculum focuses on challenging students’ thinking, encouraging open-minded respectful perspectives towards others whose ways of living may be similar to or different from theirs, inviting students’ inquiries into perplexities they notice in their world, and expanding their intercultural understandings (Short, 2016).

Lacey Elisea is the first grade teacher and has been teaching preschool to first grade for six years. She has been in the Vail community for most of her life and has strong ties to the community. Cassandra (Cassi) Sutherland has been at Creation School for three years. Initially, she taught preschool (2-3 year-olds) and for the two years she has taught both physical education (P.E.) and art for the K-5 school. She focuses on classroom collaborations with teachers to create relevant learning experiences and rigorous school projects that encourage students’ critical thinking about themselves and the world.

Our desire to collaborate across content areas and bring authentic experiences to our students led us to an integrated curriculum study of the Olympics (see the Elisea and Metzger vignette in this issue). Due to Covid, both the 2021 Summer and 2022 Winter Olympics were held in one school year. The Olympics provided us with an opportunity to build a curriculum with different world cultures/countries coming together to celebrate individual and team abilities, teamwork, and sportsmanship. We believed a study of the Olympics would expand students’ perspectives of the world, their understanding of themselves and their abilities, their respect for those who are different from them, and their realization of common human experiences, desires, and emotions that they share with others in the world (Short & Thomas, 2011).

Learning About the Olympics

Jonathan Barnes (2011) points out that cross-curricular learning can strengthen “left brain – right brain” connections by providing students with real life scenarios and opportunities to experience and apply their learning in different areas and contexts. By integrating areas of the curriculum students have broader contexts to connect information and concepts which expand and deepen their learning and understanding.

To introduce the Olympics Cassi read All About the Olympic Games by Marisa Boan (2021) in art class. The book describes how the Olympic games began in Greece and how the Olympic flame is lit in Olympia and passed hand-by-hand to runners all the way to the Olympic Stadium. Cassie and the students located Olympia and Tokyo, where the 2021 Summer games were being held at the time, on a world map. This led to questions such as, “What do they do if they have to cross an ocean or other water?” and students suggested possibilities. Students talked about uniforms and representing a team or country. Some students wanted to wear uniforms for P.E. the next day. Many wore USA apparel, but some wore soccer uniforms from different countries like Brazil and the Czech Republic. Students made torches with card stock and tissue paper (see Figure 1) which they took turns passing to each other.

Figure 1. First graders holding their Olympic torches made in art class

Cassi shared information about the opening ceremony and lighting the Olympic flame and the closing ceremony where the Olympic flame is extinguished. She kept many Olympic books in the art classroom for students to browse and for her to pull to read. This also helped cultivate students’ reading habits (Affinito, 2021).

Summer Olympic Games

The Summer Olympics were held in Tokyo, Japan, in 2021. Students studied the Olympics in their classroom with Lacey and in P.E. and art with Cassi. Cassi and Lacey read as much global literature as they could related to the Olympics but not all read-aloud books were global literature due to availability. P.E. classes were two days a week. Cassi used one day to read about the Olympics and practice events and the other day as the Olympic Game Day for each class in Kindergarten through fifth grade.

To begin, Cassi read I Live in Tokyo by Mari Takabayashi (2004) to provide first graders with information about Tokyo. Cassi also read The Triumphant Story of an Underdog Olympig by Victoria Jamieson (2016). This book is about a pig who competes in many events and never wins but keeps trying until he eventually gets discouraged. During the book the pig talks to his mother. Cassi asked the students how they thought Olympig’s mother would respond. Students agreed she would reply, “It’s ok if you don’t win, I still love you.” Kora said, “Mom would say, ‘It’s ok, try again.'” While reading the book, students noticed the differences in the animals’ bodies and said that a pig couldn’t win a race against a cheetah. This led to a discussion of how body types relate to abilities for them, animals, and Olympic athletes.

Figure 2. Kindergarten performing the torch relay

After reading the book, students talked about the importance of practicing the sport or event that an Olympian competes in and how no one can win the Olympics without practice. They had a broader discussion of the importance of practice in everything, including things other than sports, such as math, reading, writing, and drawing.

Events for our Summer Olympics included sprint, long distance, discus (throwing a frisbee), and shot put (throwing a wiffle ball). Students practiced these during P.E. in preparation for Olympic Game Day. Each class had a torch relay to signify the torch moving from Olympia to Tokyo (see Figure 2).

Figure 3. Kindergarten lighting the Olympic flame

On Olympic Game Day Cassi entered the classroom carrying an Olympic torch with the Olympic theme playing on her phone. Students had an Olympic parade as they walked over to a bowl with the Olympic torch and threw the tissue paper in the bowl to signify the start of the games with the lighting of the Olympic flame (see Figure 3).

Summer Olympics Game Day

In kindergarten, students had individual sports but the focus was not on winning and losing. Students participated in shot put (throwing a wiffle ball), discus (throwing a frisbee), and some short distance sprints. Kindergarten students finished with a team relay after which each of them received a gold medal after crossing the finish line. The whole class stood on the podium while the national anthem was played.

In first through fifth grades, students competed against their classmates in the four individual events they practiced and the team relay event at the end of the class. Children chose whether or not to participate in the individual events. Participation was high and no child sat out every event.

Figure 4. First grade winners of the sprint event

The first three finishers in each event received a medal (gold, silver, or bronze) in our medal ceremony where we held up the American flag while the USA National Anthem played. The finishers stood on the podium and received their medals (see Figure 4). The medal ceremony encouraged students to be happy for their classmates who won the event. Cassi discussed with the students that it’s natural to be disappointed to not win but important to celebrate that they tried and participated; everyone has different talents and abilities. Students took turns presenting the winners with their medals. This encouraged sportsmanship and helped those who were upset they didn’t win to process their emotions and move on for the next event.

Figure 5. First grader Nolan finishing the relay for his team

The last event of our Summer Olympics Game Day was a relay in which everyone in each class participated. There was one team that consisted of the whole class. One by one students ran a lap around the playground and passed the baton to the next child. When the last child was running, we held up a finish line to mark the end of the relay. The last child of the team relay ran through the finish line (see Figure 5).

Figure 6. First graders celebrating their gold medal victory in the team relay

When the class relay finished, all students stood on a large podium for the medal ceremony as a class “team.” Every child in the class received a gold medal while the National Anthem played (see Figure 6). This was a great way to end the events.

After the relay medal ceremony, each class walked over to the Olympic flame and removed the tissue paper to represent extinguishing the flame for the Summer Olympic closing ceremony.

Winter Olympic Games

The Winter Olympics occurred in Beijing, China, in 2022. As an introduction, Cassi read Team Sports of the Winter Games by Aaron Derr (2020). Each class had a torch relay in which every student participated. Students cheered for their classmates as they finished a lap with the “torch.” As they took turns running, Cassi would ask, “Where are they going?” and students would respond, “Beijing, China!” For the opening ceremony Cassi arrived at each classroom with a “torch” in her hand and the Olympic theme playing on her phone. Students paraded with her to the bowl to “light” the Olympic flame to begin their games.

Our Winter Olympics included four sports: speed skating (felt attached to shoes to move on the gym floor), luge (two scooters tied together), curling (using air stones and a mat, like air hockey), and ice hockey (played as field hockey). Cassi designed these events to support students with different abilities and skills, giving everyone opportunities to win. Speed skating was as much about students keeping their feet with felt attached on the floor as it was about being fast. It also required patience if the participant “lost” a felt skate. Luge was easier for students who weighed less and were smaller. Scooters were tied together and students lay on their backs and pulled themselves to the fence with a rope. Curling was good for students with a light touch and consistent throw. Students also needed to understand the rules quickly and know how to add and subtract.The last event, ice hockey (field hockey) was a team sport in which everyone received a medal. As an active exercise it catered to the competitive students who were fast and coordinated.

Figure 7. Kindergartners participating in the luge event

The first event was the luge. Two participants raced at a time in elimination rounds. Each would lie on a sled with their feet pointed toward the finish line (a fence). Cassi gave them a rope attached to the fence and each child pulled their body to the fence while trying to keep control and not fall off the sled. The first child to the fence won. The winners moved on and competed against each other in elimination brackets.

To learn about speed skating and the rules, Cassi read Speed Skating: Global Citizens: Olympic Sports by Ellen Labrecque (2018). Speed skating required practice and once again Cassi and students discussed the importance of practicing something to improve skills. To speed skate, students stood on pieces of felt and tried to scoot around a loop of cones in the gym (see Figure 8). After the individual speed skating event, the whole class participated in a speed skating relay where the class was divided into two teams and they relayed around the cones with batons.

Figure 8. First graders practicing speed skating

Figure 9. First graders competing in curling

To introduce curling, Cassi read Curling: Global Citizens: Olympic Sports by Ellen Labrecque (2018). Curling was similar to air hockey. Students were divided into teams. In every round, the air stone closest to the inside of the circle won. Participants could count all their stones that were closer to the center of the circle than their opponents, but none that the opponent had beaten. The last stone thrown in a round was the hammer which was used to, hopefully, hit an opponent’s stone out of the circle while simultaneously putting the participant’s stone into the center circle. Curling was a favorite of the students.

An awards ceremony occurred after each event. Students stood on the podium to receive their medals while the National Anthem played. For curling, each smaller team competing on a mat received a gold or silver medal depending on which team won the game. Everyone medaled in curling as long as they participated.

Figure 10. First graders competing in field hockey

The final event was ice hockey. Cassi read Ice Hockey: Global Citizens: Olympic Sports (Labrecque, 2018) to introduce the event. For this event, the entire class was split into two teams to play field hockey (see Figure 10). Everyone in this event got a medal. In the case of a tie, both teams received gold, otherwise one team received gold and the other silver.

The end of the P.E. Winter Olympics was marked by each class extinguishing the Olympic flame.

Classroom Connections

Students were excited about the Olympics and discussions of the events, rules, teams, winning and losing bubbled up in the classroom. During class, Lacey showed clips of events occurring in Tokyo or Beijing and the award ceremonies. Student experiences at school encouraged them to make connections with the Olympic events at home and they came to school talking about what they’d seen on television or discussed with their families.

Lacey saw this as an opportunity to invite first graders to write about their Olympic experiences. As Stephanie Affinito (2021) states in Leading Literate Lives, it’s important to provide students with outlets “to write from their own personal experiences to learn more about themselves” (p. 121). Students wrote opinion papers on their favorite winter sports, providing reasons for their choice. Many students also discussed their enjoyment of P.E. and art in their reasons for picking the sport. The topic was relevant to their lives, which created an ease in the writing process.

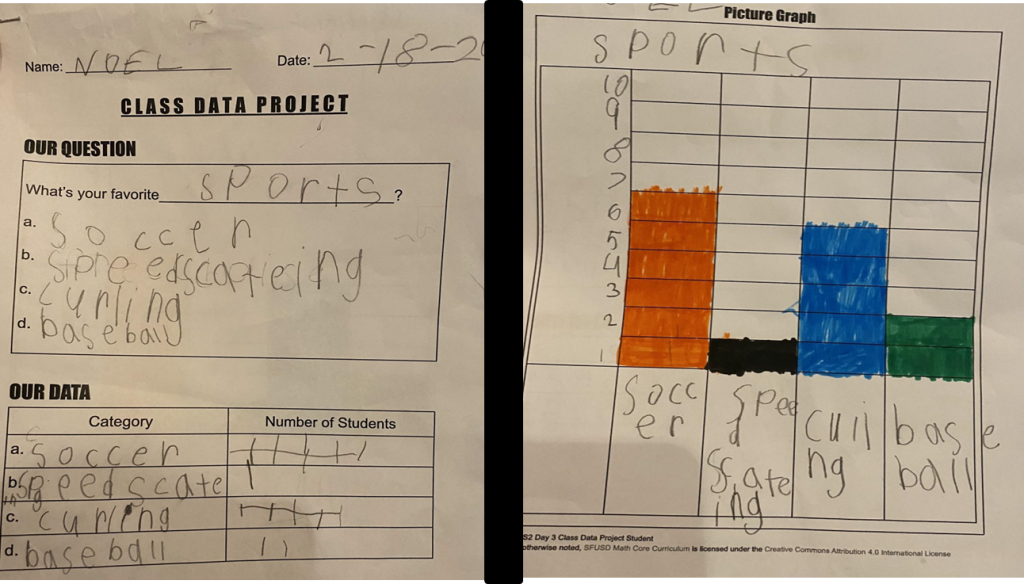

Olympic learning occurred across other content areas. For example, in math students interviewed their classmates to collect data on favorite sports. Noel selected soccer, speed skating, curling, and baseball as categories in which students could vote “because these are my favorite sports.” Prior to the Olympic study, Noel and other students did not know what speed skating and curling were. Noel converted his data into a picture graph showing what he discovered (see Figure 11).

Figure 11. Noel’s data (left) and picture graph (right) of his classmates votes

Figure 12. C.J. sharing his findings about the Olympics in the Scholastic Children’s Dictionary

During free reading, C.J. was browsing the Scholastic Children’s Dictionary (2002) and was excited to find information about the luge (see Figure 12). He then looked for the other sports he’d learned about in class. He said, “I love reading more about Olympic sports.”

Social Emotional Learning

Our Olympics study also invited students to reflect on themselves. The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) (2022) defines social and emotional learning as “the process through which children develop skills, knowledge, and attitudes necessary to understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions.” Studying the Olympics offered students an opportunity to use and develop many social emotional skills.

One of the books Lacey read for the Winter Olympics was What are the Winter Olympics? (Herman, 2021). In the first chapter Herman shares Shaun White’s story, including how he grew up in San Diego, California, a place without snow, yet became a gold medalist in snowboarding. Students related to his story because we do not get snow in southern Arizona. Herman explains how White had won gold medals in the 2006 and 2010 Olympics and was favored to win the gold medal in 2014 but finished fourth. Students discussed how they would feel if this happened to them. Riley said, “I would continue to practice for next time,” while John stated, “I would be proud of my other gold medals.”

After reading about Shaun White, Lacey the students watched a video clip of his triumphant return to the Olympics in 2018, when he again won the gold medal. White was behind the other snowboarders until his last run but he won the event. Olympians who lost after being ahead of White congratulated him. Lacey asked the first graders, “How do you think the Olympians who lost are feeling?” Dean responded, “Disappointed because they lost!” Most of the class agreed. Lacey discussed with the students how the video showed Olympians who lost smiling as they congratulated White and enjoying the moment of White performing at his best with him. Students discussed emotions and ways to handle those emotions when events do not happen as one might want, reflecting also on their own experiences with our Olympics.

Reflection

We decided to study the Summer and Winter Olympics as they were happening in Tokyo and Beijing because we believed that study would expand students’ perspectives and connections with different parts of the world, their understandings of themselves and their abilities, their respect for those different/more skilled than them, and their realization of the common human experiences, desires, and emotions they share with others around the world (Short & Thomas, 2011). We are confident that occurred. Through experiences with global literature, nonfiction books, news reports, video clips, and practicing and competing themselves, students learned about unfamiliar places, sports, and athletes.

The study also provided us with an opportunity to celebrate individual and team abilities, teamwork, and sportsmanship. Students saw how countries and athletes from around the world came together for a global event. They learned to challenge themselves, work towards common goals, celebrate individual and team abilities, and show disappointment if they lost, but also congratulate the winners. They learned and experienced that people of all ages around the world share a universal humanness related to desires, needs, and emotions. In addition, the study provided the opportunity to integrate reading and writing across the curriculum offering multiple broader contexts for students to connect information and concepts and expand and deepen their learning in authentic ways (Barnes, 2011).

As we continue to grow our curriculum, we hope to incorporate more global literature and in-depth studies of multiple cultures/countries. We also hope to incorporate more teachers and provide more opportunities for these types of learning experiences.

References

Affinito, S. (2021). Leading literate lives. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Barnes, J. (2011). Cross-curricular learning 3-14. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Boan, M. (2021). All about the Olympic games. Independently published.

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. (2022). Fundamentals of SEL. https://casel.org/fundamentals-of-sel/#:~:text=SEL%20is%20the%20process%20through,and%20make%20responsible%20and%20caring

Derr, A. (2020). Team sports of the winter games. South Egremont, MA: Red Chair Press.

Herman, G. (2021). What are the Winter Olympics? New York: Penguin.

Jamieson, V. (2016). The triumphant story of an underdog Olympig. New York: Puffin.

Labrecque, E. (2018). Ice hockey: Global citizens: Olympic sports. Ann Arbor, MI: Cherry Lake.

Labrecque, E. (2018). Curling: Global citizens: Olympic sports. Ann Arbor, MI: Cherry Lake.

Labrecque, E. (2018). Speed skating: Global citizens: Olympic sports. Ann Arbor, MI: Cherry Lake.

Scholastic. (2002). Scholastic children’s dictionary. New York, NY: Scholastic.

Short, K.G. (2016). A curriculum that is intercultural. In K. Short, D. Day, & J. Schroeder (Eds.), Teaching globally: Reading the world through literature (pp. 3 – 24). Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Short, K.G., & Thomas, L. (2011). Developing intercultural understandings through global children’s literature. In R. Meyer & K. Whitmore (Eds.), Reclaiming reading: Teachers, students, and researchers regaining spaces for thinking and action (149-162). New York: Routledge.

Takabayashi, M. (2004). I live in Tokyo. New York: Clarion Books.

Cassandra Sutherland has taught at Creation School for three years and is the physical education and art teacher in the elementary school.

Lacey Elisea has taught in early childhood classrooms for six years and is the first grade teacher at Creation School.

Authors retain copyright over the vignettes published in this journal and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under the following Creative Commons License:

WOW Stories, Volume X, Issue 3 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/volume-x-issue-3-fall-2022/3/8.

WOW stories: connections from the classroom

ISSN 2577-0551

Hello,

I really enjoy reading the reviews and this website. I am wondering what are

the guidelines for :

the review board member selection in different sections

review guidelines for a reviewer

I checked for the contact info for reaching review board member (s) but was not able to locate it or missed it.

Thanks

Thank you for leaving a comment on your question. You can find the review guidelines and other online forms at ” http://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesguide/ “.

Thanks,

yoo kyung