Multicultural Conversations: Online Literature Circles Focused on Social Issues

By Judi Moreillon

A Single Shard, The Other Side of Truth, The Breadwinner, Homeless Bird, Monster, and The Watsons Go to Birmingham—1963 are some of my favorite multicultural middle grade novels. Librarians who are new to a school, however, inherit a collection of books selected by their predecessors. In order to find these “classic” and other similar titles, I had to dig deep into our school library collection since the collection I inherited during the 2008-2009 school year was not characterized by a great deal of cultural diversity. Still, when I was called upon to provide booktalks to seventh and eighth grade students, I chose as many titles as possible by Linda Sue Park, Beverly Naidoo, Deborah Ellis, Gloria Whelan, Walter Dean Myers, and Christopher Paul Curtis. But despite my best efforts, our mostly dominant-culture students persisted in checking out culturally-familiar or culturally-neutral titles (For me, the vast majority of fantasy and science fiction books fall into the latter category). At the end of each class period after my booktalks, I found that most multicultural titles remained untouched on the browsing tables.

Rochman (1993) wrote, “It’s obvious that for mainstream young people, books about ‘other’ cultures are not as easy to pick up as YM magazine, or as easy to watch as ‘Beverly Hills 90210.’ And, in fact, it shouldn’t be. We don’t want a homogenized culture. If you’re a kid in New York, then reading about a refugee in North Korea, or a teenager in the bush in Africa, or a Mormon in Utah, involves some effort, some imagination, some opening up of who you are” (p. 25). So, I bided my time but didn’t give up on the idea of broadening and deepening students’ transactions with multicultural literature.

Context

In the 2008-2009 school year, I served as the teacher-librarian at Emily Gray Junior High-Tanque Verde High School in the American Southwest. Our schools are located in an affluent, overwhelmingly white, European American community and share a campus and a library. From the beginning of the school year, I noticed a definite trend in students’ book preferences. In independent book checkouts, mainstream, popular-culture titles dominated students’ choices: The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants and Twilight series, the Eragon and Eldest series, and current and classic fantasy and science fiction titles.

This observation aligns with the results of a recent study of award-winning books and titles popular with teens. Koss and Teale (2009) analyzed 370 titles published between 1999 and 2005. They noted that fiction was predominant, comprising 47% of these titles; most of these titles were contemporary realistic fiction. European Americans were the predominant culture at 32%, with African American characters making up only 5% of the characters in the fiction; other groups were even more underrepresented. Although “multicultural titles” made up 20% of these books, few portrayed multiple cultures. Thirty percent of the books analyzed were international, but the majority of these titles portrayed white characters living in European cultures.

As a middle/high school librarian, my mission is to integrate literature, information, and technology into the classroom curriculum. During that school year, I was fortunate to coteach online literature circle discussions with Jennifer Hunt, an eighth-grade Pre-AP language arts teacher in a year-long, Qwest grant-funded project she called WANDA (Works Analyzed Notated Discussed & Archived) (http://wandawiki.wikispaces.com/). We collaborated to support students’ inquiries as they participated in four literature circles, each one spanning the majority of an 8-week grading period. Over the course of the year, students discussed American Southwest themed books, fantasy and science fiction, historical fiction, and finally, the Jacqueline Woodson novels around which this article is centered.

Online Literature Circles

Literature circles provide students with choice in what they read and allow students to discuss and collaborate within an inquiry-based framework. This discussion format is intended for students to make personal connections to the texts they read and to describe and discuss the issues raised in literature selections through social discourse (Short, Harste, & Burke, 1996). The WANDA wiki-based literature circle project added an additional element to learning by providing students with the technological means to discuss books with students beyond their classroom and to collaborate with others to create Web pages to organize, discuss, and share their responses to the novels using words and images as well as multimedia. These read-write tools allowed students to discuss books outside of class time and the school day and to work in a 21st-century technology-supported collaborative environment.

All of the students in Jenni’s three sections of Pre-AP eighth-grade language arts were required to participate in four literature circles, one during each quarter of the school year. Jenni established criteria for posting to the discussion board within the wiki and for the various story-element focused pages of each literature circle wiki. Her eighth-grade student aide created the actual wiki homepage for each group and invited the literature circle group members to join. The group members then built the wiki pages on which they discussed their literature circle book.

For the first literature circle, Jenni experimented with assigning roles, such as Vocabulary Elaborator, Literary Expositor, or Background Researcher, but abandoned that structure in favor to a more collaborative approach in which students negotiated their roles and were responsible for the entirety of the wiki work rather than specific pages or parts. Students conducted all of their literature circle discussions in the wiki environment and published their responses online. Jenni and I (joined by her student teacher in the spring) read and discussed the students’ postings. We shared responsibility for participating as needed and assessing the students’ work using rubrics we jointly created. Jenni worked with the students in learning the wiki technology and recording podcasts. I took responsibility for teaching aspects of Web site design and several Web 2.0 tools to support their literature responses, including Wordle word clouds (http://www.wordle.net), a narrated slideshow tool called VoiceThread (http://voicethread.com), and newspaper clipping generator (http://fodey.com), tools which they used extensively in the final lit circle of the year. We both taught and reinforced concepts of netiquette and the ethical use of information, especially respect for intellectual property distributed on the Web.

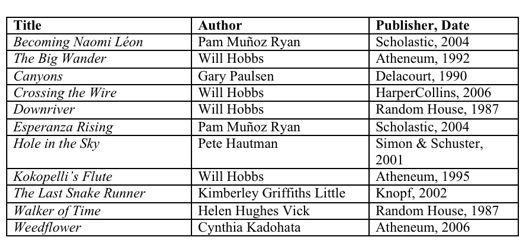

For the first wiki-based literature discussion, students chose from a set of American Southwest–themed books for which I provided booktalks (see Table I). I selected these books to encourage students to activate their background knowledge to make connections and support comprehension (Moreillon, 2007). I hoped that starting with familiar settings could help students achieve a year-long language arts objective related to articulating the impact of the setting on the mood and tone of the book. I also recommended these titles to Jenni because of the diversity of characters and cultures that were portrayed.

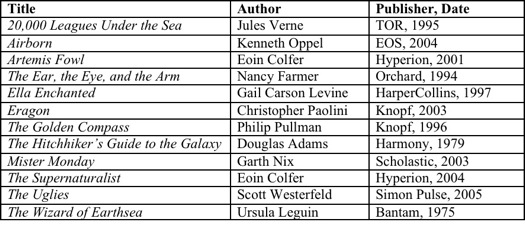

For this first online literature circle, the students formed groups with students from their own class period. Although the discussions were carried out online, they had opportunities to talk about their work face-to-face in the classroom. (Go to http://wandawiki.wikispaces.com/Southwest+Literature+Circle+Books) to see examples of the online discussions). This online literature circle also included conversations with university students in the School of Information Resources and Library Science at the University of Arizona. Graduate students shared their WANDA wiki experiences in an online forum during their graduate course and posted some of the eighth-grade students’ responses to these books on the Southwest Literature Web site (See http://southwestlit.com/pages/fall08.htm). The second literature circle centered on fantasy or science fiction books. Students formed groups from different sections of the Pre-AP class, which made it necessary for students to conduct all of their literature circle conversations and to negotiate decisions about their wiki work virtually. In order to select these titles, students began by searching online for book reviews from a teacher-selected list and were invited to recommend additional titles. The students determined their top three choices and formed groups (See the wikis at http://wandawiki.wikispaces.com/Fantasy+%26+Science+Fiction+Wikis). Table 2 shows the titles students chose.

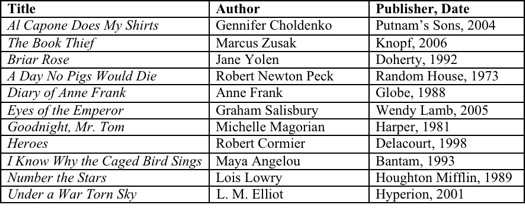

For their third literature circle selections, students chose historical fiction that addressed the time period they were studying in their social studies class. Sarah Ewing, the student teacher who joined the class in the spring, provided a list and students added titles that met the historical time-period criterion. Again, they formed groups from different classes. (See http://wandawiki.wikispaces.com/Historical+Fiction+LC). Table 3 shows the historical fiction titles student read and discussed.

A Window Opens

In the spring, Jenni, Sarah and I brainstormed possible authors for an author study focus for the last literature circle of the year. Although students were reading titles with more diversity due to the literature circles, I saw the possibility for opening an even wider window on the world. “The lack of cultural diversity in YA literature indicates that educators will need to make special efforts to seek out and use quality books that include diverse characters, and that publishers should increase their efforts to make available YA books that include multicultural characters and discuss issues related to race and diversity in significant ways” (Koss & Teale, 2009, p. 572).

I shared with Jenni and Sarah my less-than-positive experiences in encouraging students to choose multicultural titles for class assignments and independent reading. I also shared my admiration for Jacqueline Woodson’s novels and noted that when I arrived, our school only had one of her titles in the collection. Woodson’s books were some of the first I purchased for our school. I booktalked several titles for Jenni and Sarah and described the responses of preservice classroom teachers and librarians to the topics and themes in these books. We agreed to focus the fourth and final literature circles of the year on Woodson’s work.

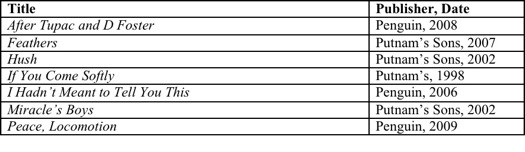

First, we asked students to research the author using TeachingBooks.net, a subscription database of information about children’s and YA authors and their work. Next, students read reviews of Woodson’s novels. Then they selected their top three titles and formed literature circle groups. (See http://wandawiki.wikispaces.com/Woodson+Author+Study). Assuming that we would need to push students to go deeper, we decided to structure these literature circles more than the previous three circles. One of our goals was to challenge students’ preconceived notions and worldviews by prompting them to discuss the social issues raised in these stories. Table 4 shows the Woodson novels students read and discussed. Hush and If You Come Softly were discussed by two different groups.

Teacher-Directed Discussion Questions

In order to focus the literature circle discussions on social issues, Jenni posted these questions: “What are the social issues in this book (e.g., crime, abuse, racism)? How does Woodson’s presentation of these issues confirm or challenge your preconceived ideas about these issues? What can you learn from this?” (These questions, which were posted on March 19, 2009, and students’ responses are on the discussion tab from the main page of each group’s wiki.)

All students responded to these questions, and many answered in terms of their preconceived ideas. Students discussed divorce and foster families, war and peace, the impact of race on the 2008 presidential election, interracial friendships and dating, and stereotypes of “popular girls” (white), poverty and abuse happening more often in “other” families, or “bad guys” (race and crime) as portrayed in movies or as reported in the media.

Racism is a frequent topic in Woodson’s work. These snippets from students’ discussions focus on that issue. Keith read Hush and wrote: “It shows that even cops, who are supposed to be good people, sometimes kill just based on race.” His group mate Mckenna extended that thought, “It teaches us how terrible people on the other side of the racial problem [African Americans] feel.” In a Hush discussion group, Carolina wrote, “We normally assume African-Americans or Mexicans to be criminals or to be guilty, and that is racism.”

Figure 1: Newspaper Clipping. Plot Page for Hush Group 2 by Adam B., Maddie C., Paul H., Melissa M., Nat L., and Lily N. (http://hushii.wikispaces.com/Plot)

When Mark wrote, “Racism is slowly dying,” Mckenna replied, “but racism also affects more than just white and black people. Asian, South American, and Mexican people are also subject to racism. (And any other race, for that matter.) What I meant is that we live in a wealthier part of Tucson. We rarely hear of racism cases or anything like that… When I read it [Hush], it sort of gave us a glimpse of what the real world can be like…. Many of us would have previously overlooked something like that.” Nat who discussed Hush with another group said, “Living in a place like we live in can really make you brush off racism like it is nothing.”

Figure 2: Hush Group 1 VoiceThread by Eme, Keith, and McKenna (http://hushi.wikispaces.com/Plot) ![]()

Broadening and Deepening the Conversation

After discussing students’ initial responses, Jenni, Sarah, and I felt that the students had just scratched the surface of their prejudices. To encourage them to dig deeper, we invited library student aides, fifteen high school students in grades 9-12, to read the students’ wiki pages that described the characters, settings, and plots of these books and then to enter into the March 19th social issues discussion. Library aides were instructed to post thought-provoking questions or comments to stimulate the eighth-graders’ responses.

High school students asked junior high students to describe how issues of race play out on our campus. Some of the eighth-graders had not yet expanded their discussion to include instances of racism that involve groups other than whites and African Americans. One Latina library aide shared her experiences of being an “other” on our campus. Another aide asked junior high students to speculate on how Woodson would have been treated for speaking out against racial prejudice in Nazi Germany. Although many greatly benefited from this probing, I felt that one group still hadn’t fully examined their stereotypes related to race, poverty and sexual abuse.

Figure 3: I Hadn’t Meant to Tell You VoiceThread: Plot Page by Courtney, Willow, Laura, Kenza, Marisa, and Rachel. http://ihadntmeanttotellyou.wikispaces.com/Plot ![]()

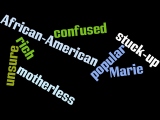

Figure 4: I Hadn’t Meant to Tell You Wordle for Marie by Courtney, Willow, Laura, Kenza, Marisa, and Rachel (http://ihadntmeanttotellyou.wikispaces.com/Characters)

On March 31st, I posed a question to the I Hadn’t Meant to Tell You This Group:

“If—before you read this book—someone told you that in this story there is one white girl and one black girl and that one is rich and lives in a supportive family and the other is poor and is abused by a close family member, then asked you to predict which girl is white and which girl is African American, would you have correctly predicted the race of each character?”

Of the six girls in this literature circle group, five wrote at length about how they would have been “wrong,” and would have predicted the poor, sexually-abused girl was black. (The sixth girl did not respond to this question.) Library aides made similar comments related to their own prejudices. This discussion is worth reading in its entirety at http://ihadntmeanttotellyou.wikispaces.com/message/view/home/10247836. As the conversation was winding down, one library aide wrote, “The best way to shatter stereotypes is to give strong examples against them and this story contradicts the stereotypes on almost every level.”

Figure 5: I Hadn’t Meant to Tell You Wordle for Lena by Courtney, Willow, Laura, Kenza, Marisa, and Rachel

Paul identified Jacqueline Woodson as a “crusader against racism in the U.S.” Although some students declared themselves to be free of racial prejudices, others recognized that Woodson’s stories encouraged them to consider race, some for the first time. Emi wrote, “She [Jacqueline Woodson] made me think about how black people think about being black. I guess I never really considered that side of things before.” Some were able to put themselves in the shoes of an interracial couple (If You Come Softly) and noted that they didn’t believe they could handle the pressure from parents, friends, or society that is often a consequence of an intimate interracial relationship. Jeremy, a student who also discussed that title, wrote, “I learned how harsh the real world can be and how much worse it is if you have more melanin.” These responses show Rosenblatt’s transaction theory (1978) was at work in the 21st century. Meaning in these novels was negotiated by these readers, the texts they read, the multimedia responses they created, and the author Jacqueline Woodson.

Figure 6: If You Come Softly Group 1 VoiceThread: Characters Page by Emi O., Abby R., Rachel F., Alex R., Jen D., and Paige G. http://ifyoucomesoftlyi.wikispaces.com/Characters ![]()

Summary

The high-quality, multicultural literature we selected for this project invited readers to educate both their hearts and minds (Bishop, 1994). Many students made critical first steps in walking in the shoes of an “other.” Some began to examine their preconceived ideas on social issues. In the online literature circle discussion forum, students negotiated meaning socially and challenged each other to deepen their engagement with the texts. They practiced and developed careful “listening” (reading) and communication (writing) skills and collaboration that are necessary in 21st-century learning environments.

The students’ wiki-based conversations became, in fact, other texts for exploration. Their written thoughts, questions, and responses provided critical information for us. In classroom-based literature circles with just one classroom teacher present, facilitating multiple groups reading different titles is a challenge. The ongoing nature of literature circles makes it difficult for school librarians to participate, especially at the middle and high school levels, where the time commitment restricts them from interacting with students in other classes at regular times over a period of several weeks. The fact that these discussions occurred online allowed the classroom teachers and me to monitor the conversations and interject thought-provoking comments and questions as needed to push the students to more critical responses and interactions. Instead of participating in transient oral exchanges, the meanings readers shared were student-generated written texts and multimedia representations that they, their high school discussion mates, their teachers, university graduate students, and the world could savor and question, reflect upon, and revisit.

By selecting multicultural novels and bringing students’ attention to the social issues in these stories, we encouraged them to examine and re-examine their perceptions of the world. “Books can make a difference in dispelling prejudice and building community: not with role models and literal recipes, not with noble messages about the human family, but with enthralling stories that make us imagine the lives of others. A good story lets you know people as individuals in all their particularity and conflict; and once you see someone as a person―flawed, complex, striving―then you’ve reached beyond stereotype” (Rochman, 1993, p. 19).

If the Woodson circles had not been conducted at the end of the school year, the next step might have been to involve students in literature discussions of international titles with many different “others.” Students’ summative portfolios assessments and self-reflections showed that the literature circle wikis had a positive impact on their learning this year and pushed them to develop as collaborators and content creators. Students shared that these final literature circles, in particular, made them consider new points of view. As Taoist philosopher Lao Tzu wrote, “A journey of a thousand miles must begin with a single step.” We believe these students have taken an important first step.

References

Bishop, R. S. (1994). Kaleidoscope: A multicultural booklist for grades K-8. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Koss, M. D. & Teale, W. H. (2009). What’s happening in YA literature? Trends in books for adolescents. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 52 (7), 563-572.

Rochman, H. (1993). Against borders: Promoting books for a multicultural world. Chicago: American Library Association.

Rosenblatt, L. (1978). The reader, the text, the poem: The transactional theory of the literary work. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Short, K.G., Harste, J., & Burke, C. (1996). Creating classrooms for authors and inquirers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Young Adult Literature Cited, All Written by Jacqueline Woodson

(2008) After Tupac and D Foster. New York: Putnam’s Sons.

(2007) Feathers. New York: Putnam’s Sons.

(2002) Hush. New York: Putnam’s.

(2006) I hadn’t meant to tell you this. New York: Penguin.

(2006) If you come softly. New York: Speak.

(2002) Miracle’s boys. New York: Scholastic.

(2009) Peace, locomotion. New York: Putnam’s Sons.

Collaborators’ Bios:

At the time of this project, Judi Moreillon was the teacher-librarian at Emily Gray Junior High – Tanque Verde High School in Tucson, Arizona and an adjunct assistant professor teaching multicultural children’s and young adult literature at the University of Arizona. She is now on the faculty in the School of Library and Information Studies at Texas Woman’s University in Denton, Texas. Contact Judi at: jmoreillon@twu.edu

Jennifer Hunt is the 8th-grade Pre-Advanced Placement language arts teacher at Emily Gray Junior High School in Tucson. In 2009, her classes earned 2nd place in the ABLE IT in Schools Achievement Award for this work and the school received 15 notebook computers, a cart, and professional development courses for all Emily Gray Junior High School teachers. The WANDA Wiki Web site also earned the Arizona Technology in Education Alliance 2009 Exemplary Middle School Web Site Award. Contact Jenni at: jhunt@tanq.org

Sarah Ewing was the student teacher in Ms. Hunt’s classroom during the spring semester of this project. She is now a first-year 7th-grade language arts teacher at Emily Gray Junior High School. Contact Sarah at: sewing@tanq.org

WOW Stories, Volume III, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesiii1/.

One thought on “WOW Stories: Connections from the Classroom”

Comments are closed.