“Stereotypocide”: Rethinking Cultural Traditions

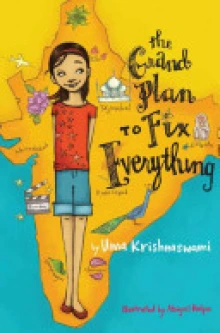

Korea’s traditional beauty is mirrored in its architectures, symbols, pottery, and ancient palaces and make up most of the common “Korean” postcard faces I encountered when I visited one of the most popular and largest bookstores in Seoul, Kyobo books. I mumbled, “interesting,” and felt and tasted a kind of betrayal. I felt I have fought consistently for a postcolonial non-Eurocentric portrayal of Asian and Korean cultures in my children’s literature studies, yet such traditional subjectivity is produced and consumed internally in Korea as a mark of Koreanness. Tradition is like a double edged sword providing rich cultural facets and, concurrently, glaringly flawed over-representations of a culture, producing a “tunnel vision” (Scott,1998, p.47) of narrow understanding of that culture. Traditions can serve as a unique and differentiating feature of a culture, helping people identify with their own cultures when juxtaposed against others’ cultures. Perhaps the overly generic and contemporary nature of so many cultural representations that seem to span a large number of cultures drives a perception that traditional views are more defining. In my review of the Grand Plan to Fix Everything, by Uma Krishnaswami, my appreciation of its cultural authenticity is heightened as the protagonist, Dini, brings a wide range of contemporary depictions of the richness of Indian culture. In my review of this book, I recalled how the children’s literature of South Asian cultures is heavily focused on traditional cultural practices with its emphasis on old traditions. As a result, folklore icons, such as monkey gods and exotic animals as well as cultural icons (i.e. sari, diwali, wedding, and henna), dominate the portrayal of those cultures.

My aesthetic responses to the Grand Plan to Fix Everything come from the depiction of the contemporary nature of Indian culture (pop cultures, celebrities, mass media, friendships, and peer pressures) that creates a universal connectedness across a host of other childhood cultures, yet still retains its relevant representation of India. An interesting parallel I recall is a story from a Nigerian story teller, Chimamanda Adichi, whose American roommate was shocked to learn that Adichi listened to Mariah Carey CDs instead of traditional African “village” songs. Contemporary multicultural and international understandings are as important as knowing the traditions in a culture. When cultural readings invite readers into a culture that not only provides a historical view, but also shows the current responsive and evolving characteristics of a culture, authentic cultural experiences are most likely to happen – as in how a Grand Plan to Fix Everything keeps reminding us that Bombay is the old name for the city of Mumbai.

Stereotypocide is my own term combining stereotype and suicide. I use it to warn of the danger that comes in a single representation of a culture. When tradition is the only illustration of a culture, cultural stereotypes are born. Such stereotypes emanate from an unbalanced understanding that builds cultural constructions powered by a simplistic view that emphasizes only differences. This culminates in cultural depictions based only on differentiation and not on connectedness. When the contemporary side of a culture is not appreciated or is underrepresented, that culture becomes a victim of itself. It initiates suicidal cultural components that negate cultural pride and identity, robbing a culture of its richer and complex aspects, solely to be portrayed by what is old and traditional.

Culture is a rich tapestry of intricate and interwoven historical and contemporary threads. It may be instructive to occasionally follow only one thread at a time. If that is the only way it is viewed, however, the larger and much more aesthetic picture is lost to a lone idea that is an inadequate and singular representation of what a culture truly is.

Scott, J. C. (1998). Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition have Failed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press

Journey through Worlds of Words during our open reading hours: Monday-Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit archival stream.

I have not read The Grand Plan to Fix Everything, but found Dr. Sung's reflection thought-provoking. I have been exploring this very issue of over-representation of cultural images in my third grade classroom as we have been studying South Korea. When looking at fiction and nonfiction books about Korean culture, my students now count the number of traditional clothes they see in books and the number of modern outfits they see. We've had interesting conversations about why there is an overrepresentation of hanbok (traditional clothing). They also talk about the Korean food that is always pictured in books.

The best way I found to bring an awareness to this overrepresentation was to find as many story books as I could with New Mexico settings (there aren't that many). Not surprisingly, many iconic cultural images of southwestern/Hispanic/New Mexican were present in the books. My Albuquerque students noticed this "stereotypicide" right away. That gave us a reference point to question the pictures of South Korean foods, fashion and festivals that they repeatedly encountered in our inquiry unit. Having contemporary children's books in Korean, from South Korea also helped show a much more diverse view of life and people in South Korea.

Showing contemporary cultural images is a perplexing issue but one that deserves thoughtful consideration. We watched a video of Yu-Nam Kim during the first days of our Korean inquiry ... that was a perfect way to keep our cultural imagination open, fresh and contemporary from the get-go.