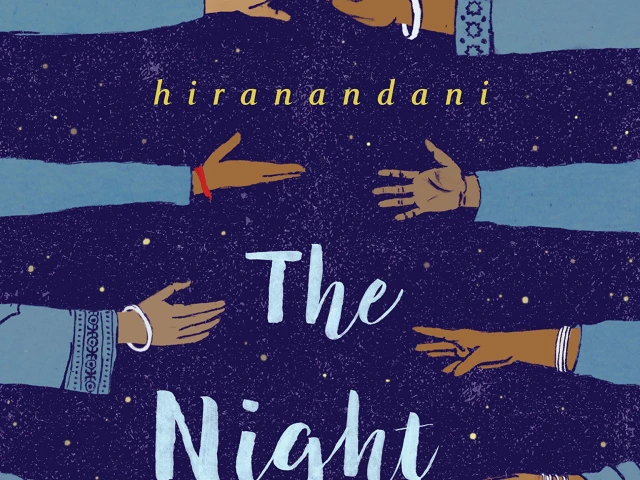

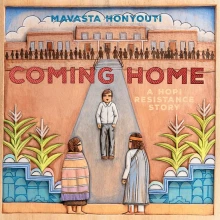

The Importance of Coming Home: A Hopi Resistance Story

Children’s literature with a focus on the Hopi Tribe has almost exclusively been written by non-Indigenous people both in past and contemporary publishing. The romanticization of Hopi ways of life has inspired many books about the tribe from outsiders’ perspectives, yet there are increasing examples of contemporary children’s literature by Hopi creators that can be used as a counterstory to outsider perspectives. Coming Home: A Hopi Resistance Story by Mavasta Honyouti (Hopi), published November 5, 2024 by Levine Querido, stands out as an exceptional informational text from a Hopi perspective created for young readers.

In Coming Home, Honyouti remembers helping his grandfather take care of their field. He tells the story of how, as a child, his grandfather was taken from his home on the Hopi reservation and placed in a boarding school at Keams Canyon, Arizona. The element of resistance in this story shines through because not only did his grandfather survive residential schooling to continue his family, but his Hopi language and culture survived. Readers see this in the language of the book as it is bilingual in English and Hopi, with translation and audio by Marilyn Parra (Hopi). Readers see this in Honyouti’s illustrations, which are painted relief carvings of Cottonwood, a deeply significant cultural practice that he learned from his father. So, though the story is about a traumatic element of Hopi history, readers see through the narrative, the illustrations, the text, and the paratextual information, that the Honyouti family and the Hopi people are resilient and thriving.

In order to understand why Coming Home has such powerful significance, one needs to understand some of the historical and contemporary context for Hopi children’s books, specifically informational texts. Children’s literature with a focus on the Hopi Tribe has almost exclusively been written by non-Indigenous people both in past and contemporary publishing. In the 1920s through 1960s, many youth titles about Hopi were published by the Bureau of Indian Affairs within the Department of the Interior, for the purpose of teaching Hopi and other Native students in BIA boarding and day schools. These titles often included Hopi illustrators and sometimes Hopi translators and so in some ways offered greater accuracy about the details of Hopi life than some of the later books with no input from Hopi people, but their underlying intention was to teach English and non-Indigenous ways of life to students forced to engage with BIA schooling. These books included narratives of Hopi life as well as traditional stories.

Frequently, vintage (and sadly also contemporary) books ignored what Debbie Reese (Nambe Pueblo) calls the curtain, the boundary of what should and should not be shared with those outside an Indigenous community. For Hopi, sensitive and private cultural information is not only protected from non-Hopi, but also much information is culturally sensitive beyond a specific clan or before children reach a certain age. Over the years, the Hopi Tribe’s Cultural Preservation Office has worked very hard to protect cultural information from these indiscretions and appropriations.

In addition, distorted children’s novels and false folktales set with a supposed Hopi backdrop began to be published at this time and continue to a lesser degree to this day. All these distorted texts were written by non-Hopi creators, sometimes even using fake Hopi names. Two widely read examples from fiction based on Hopi inaccuracies are Nancy Drew: The Kachina Doll Mystery and The Boxcar Children: Secret of the Mask, both built upon stereotypes, misinformation and exoticising the unfamiliar.

Most contemporary children’s informational texts written by non-Hopis describe a shallow Hopi history, geography, religion and ways of life in the standard 32 page picturebook format. Most books cast Hopi people in the past rather than the present and future. Most illustrations include vintage photographs exclusively or predominantly, sometimes including contradictions such as writing about the Hopi in the past while illustrating the page with a contemporary photograph. Contemporary informational children’s books about the Hopi Tribe almost always contain inaccuracies, with the same visual and textual misinformation repeated in multiple titles. Sometimes, even with Native (non-Hopi) consultants, these inaccuracies are not perpetuated. However, this misinformation has not kept the books out of school and public libraries. Some of the titles that are the most widely held in public and school libraries have inaccuracies that have even persisted through multiple editions.

For example, multiple children’s informational books contain photographs of other tribes with captions that state the image is of a Hopi person engaged in a traditional Hopi experience. In Hopi by Sarah Tieck, there is a photograph of a Navajo shepherd in Monument Valley on the Navajo Nation, but the caption states, “Sheep became important to the Hopi way of life. The Hopi spent many hours caring for their herds.” This same book captions an image of the village of Walpi incorrectly, calling it Oraibi, a different village. In Life in a Hopi Village (Pictures of the Past), there is a photograph of a Navajo woman weaving in front of her hogan, but we are led to believe she is a Hopi weaver. In The Hopi by Suzanne Freedman, illustrated by Richard Smolinski, there is a painting of a woman harvesting the Saguaro fruit with a long stick, a traditional practice of the Tohono O’odham Nation, not a part of Hopi culture. In multiple books, images from museums such as Hopi House, a museum at Grand Canyon National Park built to mimic Hopi architecture, or museum displays such as a kiva exhibit at the Museum of Northern Arizona are captioned to make the reader think it is not a museum but a real Hopi dwelling or kiva, or mislead the reader to believe that the image of a kiva is a regular house. A few texts show Hopi people wearing buckskin like other tribes, but that has never been the Hopi way of dressing. Who Were the Hopi People, a third grade geography text from 2019, shows Blackfeet women traveling using dog travois, a practice that is not a part of Hopi culture.

These are just a few of the dozens of errors I have found in children’s informational texts about Hopi people, culture and history. Although there are more than 570 federally recognized tribes in the United States, some tribes have inspired interest beyond the important encouragement to learn about local Indigenous histories. Because the Hopi Tribe has maintained the homeland they have had since time immemorial, and because their material culture and arts have inspired interest and curiosity (oftentimes veering into disrespectful and appropriative), many libraries beyond northern Arizona have books about Hopi in their collections. For example, using Worldcat, I can see that Sarah Tieck’s book is held in 388 libraries who are currently OCLC members, which means it is likely that this book is held in more than 388 libraries. Each of the books in which I have found misinformation is held in hundreds of libraries around the country. Misinformation is dangerous and damaging to all readers, both Hopi and non-Hopi, damaging to all Indigenous peoples, as well as to any reader putting trust in the author of an informational text.

If we look at traditional tales, however, there are some notable contributions from Hopi creators. Emory Sekaquaptewa (Hopi) with Barbara Pepper, published two traditional tales, one told by Herschel Talashoema (Hopi) and one by Eugene Sekaquaptewa (Hopi). These are held at about 130 libraries. Michael Lomatuway’ma (Hopi) wrote two picturebooks of traditional Hopi stories together with Ekkehart Malotki and Michael Lacapa (Hopi/Tewa/White Mountain Apache), one of which is held at 224 libraries and the other at 55. Gerald Dawavendewa (Hopi/Cherokee) wrote and illustrated The Butterfly Dance (2001, held at 164 libraries), a fictional picturebook based on Hopi ceremony, as well as a traditional tale picturebook. Meet Mindy: A Native Girl from the Southwest (2006) by Susan Sekakuku (Hopi) is, perhaps, the sole example of an informational book for young readers by a Hopi creator, and is held at 235 libraries. However, recently, Anita Poleahla and Emmett Navakuku have published board books showing items of Hopi cultural significance, Celebrate My Hopi Corn (held at 36 libraries) and Celebrate My Hopi Toys (held at 37 libraries).

In the context of this history of Hopi children’s books, Coming Home: A Hopi Resistance Story shines through with an authenticity lacking in the vast majority of informational books for children about the Hopi Tribe. It is now in at least 358 libraries around the country. I am grateful that the publisher Levine Querido encouraged Honyouti to write for children, recognizing the need to allow Hopi people to tell Hopi stories and begin correcting the vast misinformation about this topic in children’s books. Mavasta Honyouti is a social studies teacher on the Hopi reservation, helping Hopi young people everyday connect to history, and thankfully now readers beyond his classroom will benefit from his story and trust the lived experience of his family to help make sense of how Hopi history is a part of a broader history of the United States. Askwali. Thank you.

WOW Currents is a space to talk about forward-thinking trends in global children’s and adolescent literature and how we use that literature with students. “Currents” is a play on words for trends and timeliness and the way we talk about social media. We encourage you to participate by leaving comments and sharing this post with your peers. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit its archival stream.