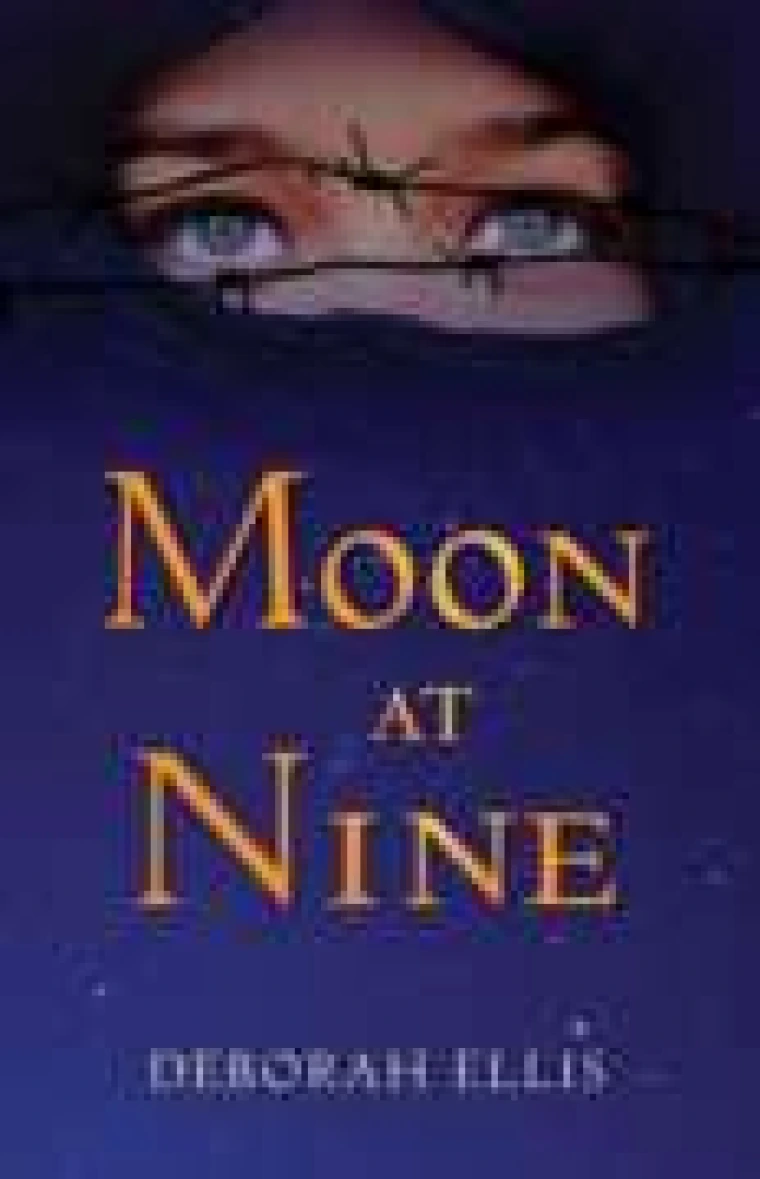

Moon at Nine

Fifteen-year-old Farrin has many secrets. Although she goes to a school for gifted girls in Tehran, as the daughter of an aristocratic mother and wealthy father Farrin must keep a low profile. It is 1988; ever since the Shah was overthrown, the deeply conservative and religious government controls every facet of life in Iran. If the Revolutionary Guard finds out about her mother's Bring Back the Shah activities, her family could be thrown in jail or worse.

9781927485576

Genre:

Fiction Historical Fiction

Region:

Iran