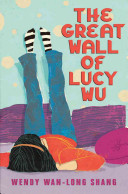

The Great Wall of Lucy Wu

Written by Wendy Wan-Long Shang

Scholastic, 2011, pp. 312

ISBN: 978-0545162159

“The Chinese part of my life just doesn’t make sense sometimes” (p.21).

This contemporary realistic fiction tells the story of eleven-year-old Lucy Wu and her journey to becoming the captain of a sixth-grade basketball team and leading her team to victory. Lucy is the baby in her family. Her big sister, Regina, is moving out to enter college and major in Chinese culture. Lucy’s big brother is known as a math geek, but often his knowledge in history impresses Lucy more than his math skills. One day Lucy’s father goes on a business trip to China and returns with a lost aunt, a sister of Lucy’s grandmother, Po Po. The news about the unexpected guest is devastating to Lucy because she was looking forward to having her own room after Regina leaves. While the “new” roommate brings new tension to Lucy at home, Lucy is also facing bullying at school. Another six grader, Sloane Conners, is the head of a group, the Amazons, so named by Lucy and her best friend, Madison. “The Amazons can make your life miserable about a thousand different ways” (p.115).

The bullying against Lucy grows harsher and more irritating as the contest for the position of captain of the sixth grade basketball team is getting close. Sloane and Lucy are in the position of competitors for the captain candidates. “Listen, Lucy, if this were for something like, I don’t know, math team, you’d get my vote in a heartbeat. But think about it. If you make captain, the team loses, everyone is going to blame you, ‘cause who ever heard of basketball team lead by some short Chinese girl?” (p. 117). The layers of Lucy’s network such as friends, family, Chinese school community, and even competitors help Lucy to become a strong candidate for captain in spite of her doubts and insecurity. Yi Po, the new aunt, also gradually encourages Lucy to be strong and confident within herself, despite Lucy’s resistance. Eventually Lucy learns to embrace her Chinese heritage and improves her Chinese language skills through her relationship with Yi Po.

The Great Wall of Lucy Wu provides a diverse portrayal of Chinese-Americans. Lucy’s voice adds contemporary experiences to depictions of Asian-American children through the individual differences among Chinese-American and Taiwanese-American characters in this book. For example, Lucy is inquisitive about Chinese culture, yet she is shy and passive about being a “hyphenated” Chinese. Speaking the Chinese language is uncomfortable and going to a Chinese school is not as exciting as playing basketball. In comparison, her older siblings have stronger pride and interest in their heritage culture as does Lucy’s schoolmate, Talent Chang “‘Are you even fluent in Mandarin?’ She [Talent] squinted, like she could tell by looking at me. If she says that I need help on how to be Chinese, I am going to wrap those eight rolls of tape around her mouth” (p.57).

At the beginning of the story, Lucy’s cultural identity weighs heavier on her American side than on her Chinese side. The different perspectives on Chinese food between Regina and Lucy are a good example. “Regina claims, ‘You are CHINESE. You are supposed to like Chinese food,’ she hissed. Lucy replies, ‘I do like Chinese food. There are plenty of dishes from Panda Cafe that are just fine with me, like their egg drop soup and chicken fried rice.’ Regina rolled her eyes. ‘That’s not real Chinese food. Panda Cafe cannot even begin to compare with the Golden Lotus’” (p.16-17). Lucy’s voice illustrates what it is like to be an American kid who happens to have Chinese heritage. In the past, many Chinese-American protagonists’ experiences in children’s literature were often depicted within historical contexts and folklore (Cai, 1994). Also new immigrant experiences tend to perpetuate only certain Asian-American experiences in literature. Lucy’s voice reflects an 11-year-old child in a contemporary setting who is not of new immigrant status. Lucy is analytically picky about food and has a love-hate relationship with her older sister like many other children. “Plunk! The waiter dropped it on my plate with a soft thud. It was small and gray, no bigger than a deck of cards. It wasn’t pretty, either, like some of the other dishes. It looked like bits of meat tacked together in one lump. What was this? “(p.14). “At that moment, I really, really hated Regina and I really really wanted a plate of lasagna” (p.12).

The author invites us to think about the delicate boundaries between a collective perspective on cultural groups and stereotypes. “Who did Regina think she was, telling me how or how not to be Chinese? I am sure there are people, maybe lots of people, in China who do not love eating pig’s ears and other weird stuff, and no one ever calls them out and tells them that they are not Chinese enough” (p.19). The author also invites individualism through Lucy’s interaction with her Taiwanese-American friend, Talent. “Everyone seems to think we should be friends because we’re both Chinese, short and in the same grade. The resemblance ends there, though” (p. 28).

Lucy’s passion for playing basketball is free from gender stereotypes. The significance of basketball for Lucy is to get away from the typical Asian girls’ childhood cultural experiences. School curriculum and social emphasis on childhood may be similar globally but also differs. The combination of an 11-year-old girl and the popularity of basketball may be more common in an American childhood, and such illustrations of Lucy’s interest and personality reinforce her being an American child. The binary notion of Chinese or American is reflectively divided through her dialogue around her non-Chinese friend like Madison. “Madison doesn’t have surprise relatives from foreign countries. Her family practically came over on the Mayflower.” (p.27). Such symbolism about “genuine American-ness” shows the author’s thoughtful observation of Diasporas’ common perception of social hierarchy without offering arguments.

Although Lucy’s story is contemporary, her Chinese heritage is awakened, provoked, and enhanced by four major people through a range of cultural components in language arts, history, tradition, and cultural ethos. Yi Po’s story serves all of those cultural aspects reflecting her life experiences in China. Kenny, Harrison, and Talent help Lucy to get close to her Chinese heritage through different peer influences. Harrison is a biracial Chinese boy to whom Lucy is attracted and his interest in Chinese language learning reduces Lucy’s resistance against Chinese school attendance. Yi Po tells family stories about how she was separated from Po Po, Lucy’s grandmother, and how the Chinese Revolution changed her life. Lucy warms up to Yi Po and the boundaries separating them dissolve. Eventually Lucy appreciates her Chinese heritage. Kenny’s insights and empathy for Yi Po’s lost childhood informs Lucy, as well as readers, about the Chinese Cultural Revolution and its historical consequences. Readers are again invited to think about the danger of collective understandings as Lucy is reminded of her grandmother Po Po’s suffering in the past due to her physical Asian appearance. This is a powerful validation of the Asian-American experience and their diasporic history in the United States. “I knew that my grandmother and mother had to work in a warehouse, cleaning, just to make some money. What I didn’t know was that they had to go to dozens of places to look for work, because people refused to hire them, thinking they were Japanese. Some people spat on them, and called them ‘dirty Japs’”(p. 39).

English and Mandarin code-switching are integrated throughout the book. This linguistic representation is unique and rare among recently published books that are multicultural. Children will benefit culturally from the code-switching and the short stories around proverbs. The use of Mandarin proverbs and symbolism and their life applications is one of the greatest features of the book. The sense of humor in this book manages sensitive social and cultural issues around stereotypical understandings in a constructive and positive way. For example, the father prioritizing math and engineering over history reminds us that the nature of stereotype is often associated with fact. At the same time the universal theme on parents’ expectations and children’s dilemma to honor their dreams and their parents’ opinions are realistically illustrated through Kenny and Lucy as their parents disapprove of history and basketball for future careers.

The author’s personal story about family photos, her correspondence with a genealogy researcher in China, and her reflection on “China’s difficult history” are grounded in this book. Although this is the first book that Wendy Wan-Long Shang wrote, the literary quality and cultural authenticity are highly appreciated. Besides authenticity in portrayal of Chinese-American culture, the authenticity of an 11-year-old girl’s childhood is thoughtfully considered based on Wendy Wang-Long Shang’s experiences with children through her various positions in the community, such as juvenile justice attorney, literacy volunteer, tutor, and mother of three.

This story shows how history is connected to our present through the relation of Lucy’s contemporary life in the United States and the surprising guest from the lost past in China. This book could be read alongside books about the Chinese Cultural Revolution, such as Red Scarf Girl (Ji-Li Jang, 1997), Revolution Is Not A Dinner Party (Ying Chang Compestine, 2007), Little Green: Growing up During The Chinese Revolution (Chun Yu 2005). These books portray young children’s reflections on the Chinese Cultural Revolution similar to Yi Po’s childhood story. Another set of books that can be read for the theme of contemporary Asian-American children learning their heritage culture is Project Mulberry (Linda Sue Park, 2005) and Archers’ Quest (Linda Sue Park, 2006). Protagonists in both books have strong American identities and gradually learn to be Korean as well through a range of journeys.

Cai, M. (1994). Images of Chinese and Chinese Americans mirrored in picture books. Children’s Literature in Education, 25, 3, 169-191.

Yoo Kyung Sung, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM

WOW Review, Volume IV, Issue 3 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/review/iv-3/

Deborah,

I appreciate that you bring your knowledge and experiences in Haiti to bear as you commented on the language Nick Lake uses and the accuracy of the historical figures he references.

I started the book after hearing Lake speak at ALA Midwinter in January – but the story was just too dark for me at the time. Perhaps, after reading your review, I will pick it up again.

Thank you for your insights.