Family Stories: A Window into Students’ Lives

By Deanna Paiva

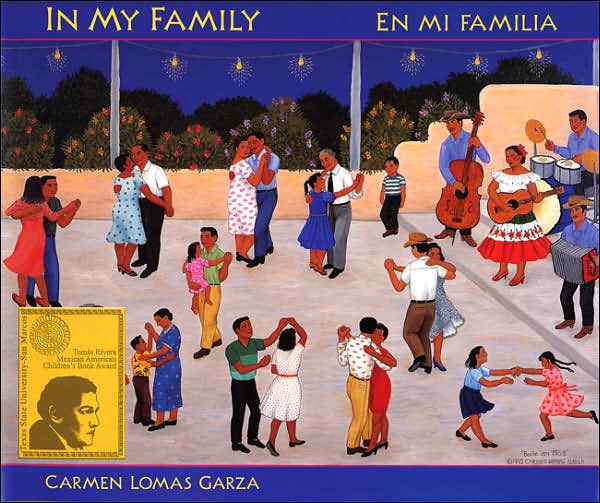

For many years teaching, I have bolstered a curriculum lacking in multiculturalism with quality children’s literature that reflects diversity in heritage, customs, and practices as well as commonalities across humanity. Multicultural literature can evoke a feeling of pride and acceptance when reading about a character who represents the reader’s culture. Because many of my students are Latino, we read books representing Latino culture, such as I Love Saturdays y domingos (Ada, 2004), Tomas and the Library Lady (Mora, 1997), and Too Many Tamales (Soto, 1993). One particular book served as my bridge to students’ culture and helped me gain an insider’s view of their families’ beliefs and values. In My Family/En mi familia by Carmen Lomas Garza (2000) helped me gain insight to their world by connecting common everyday practices with their families’ funds of knowledge. In My Family/En mi familia is a bilingual book illustrated in an almost folk style of painting. The paintings tell the stories, but each painting is embellished by short vignettes of the illustrator’s memories of life in south Texas.

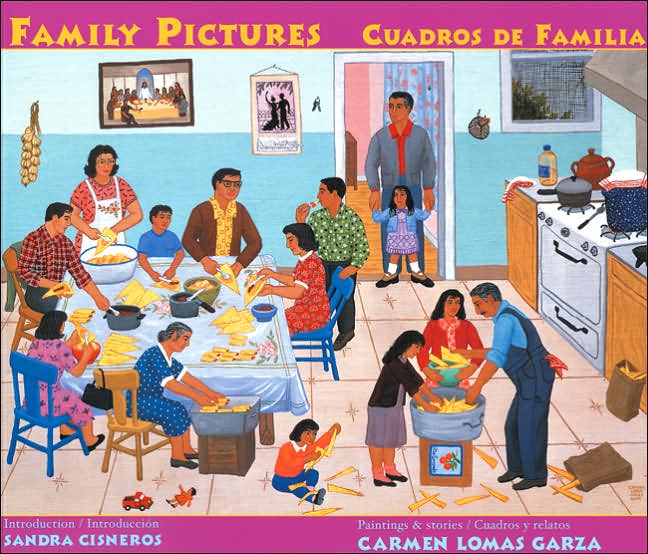

Veronica came to our classroom three times for about an hour, first to introduce the book and the task; next to collect their stories; last to have a publishing party. On her first visit, Veronica introduced In My Family/En mi familia. When she was in the room, I became the observer. On that day, I witnessed a cultural explosion in our classroom. Veronica started with Ventosa, a vignette about how to get water out of your ear. Garza shares the “home remedy” of making a funnel of paper, lighting it, and then quickly placing it in the person’s ear. The children squealed with excitement, eager to tell how they had witnessed that practice by adults in their families  in Mexico. We had planned to read only two or three vignettes, but had underestimated their excitement as signaled by their electrified chatter connecting the vignettes to their families’ experiences. We had such fun hearing their family stories pour into our discussion. I observed the children, who started out sitting quietly and cross-legged, now up on their knees engaged in small conversations with their neighbors telling their stories as Veronica turned the page to yet another colorful painting and vignette. Veronica left the book for us to enjoy and we used it to begin our daily read aloud time for several weeks with the children wanting to hear more vignettes and requesting their favorites to be read again. Wanting to extend their excitement, I read another volume of Garza’s vignettes, Family Pictures/Cuadros de familia (2005).

in Mexico. We had planned to read only two or three vignettes, but had underestimated their excitement as signaled by their electrified chatter connecting the vignettes to their families’ experiences. We had such fun hearing their family stories pour into our discussion. I observed the children, who started out sitting quietly and cross-legged, now up on their knees engaged in small conversations with their neighbors telling their stories as Veronica turned the page to yet another colorful painting and vignette. Veronica left the book for us to enjoy and we used it to begin our daily read aloud time for several weeks with the children wanting to hear more vignettes and requesting their favorites to be read again. Wanting to extend their excitement, I read another volume of Garza’s vignettes, Family Pictures/Cuadros de familia (2005).

The vignette from In My Family/En mi familia that seemed to encourage the longest-lasting dialogue was La Llorona [Weeping Woman]. La Llorona is the grim story of a woman who drowns her children in a river as an act of revenge against her absent husband and is condemned to endless nights of weeping and searching for her children. Veronica indicated that Mexican parents tell the story of La Llorona as a way to scare the children into behaving by threatening a visit from her if children act badly. I had heard many students through the years make a reference to this character, but this was my first time to see the story in print. What I didn’t realize were the many adaptations of La Llorona told in an oral tradition. For many days following Veronica’s initial visit, children brought different accounts of La Llorona to school. They were engaging in discussions with their families at home and bringing the stories back to school to share. For quite some time we began each read aloud time with new oral versions of La Llorona.

Two of my students, who are natural storytellers, were proficient with La Llorona stories. Mayra shared her own witnessing of La Llorona at the window while sleeping in the living room of her father’s house in Mexico, as well as a story of her mother’s encounter as a young girl.

When my brother and I wouldn’t go to sleep, my mother would tell us about the time that she was grabbed by the foot at the Mercado [market]. My grandpa had to pull her away and she was sure that it was La Llorona grabbing her. My mother heard, “Quiero a mis hijos” [I want my children].

Karen shared the most versions of La Llorona with her accounts of personal experiences in her aunt’s house in Mexico. While staying with her aunt who lived across from a creek, Karen saw La Llorona running at night with a baby that looked like a devil in diapers. Another night, she was wakened by a white shadow “floating with no legs” at the foot of her bed screaming, “Te voy a agarrar otra vez!” The shadow was pulling on the bed and Karen’s sister was pulling her back. “My mom and dad sleeping in another room past the kitchen, heard someone yelling, ‘No, No!’ Then a white shadow flew out the window and blended in with the house.”

In My Family/En mi familia and Family Pictures/Cuadros de familia describe ordinary everyday practices that draw from Latino families’ funds of knowledge. This knowledge includes The Healer and the all day process of making empanadas that fill every space in the kitchen and dining room. The vignette Blessing on the Wedding Day, which details a bride kneeling on a cushion and receiving a blessing from her mother, inspired Stacey to bring her special pillow to school to share. It was an intricate handmade white pillow that was blessed by the church in a ceremony when she was three years old. She explained to the class that she will use that pillow for the blessing when she gets married and other important times in her life.

I have struggled with my role as a teacher in a public school related to literature that directly involves religion. I kept skipping over two vignettes about the Virgin of Guadalupe, wondering if the public school was the appropriate place to share and discuss religious beliefs and practices. The children noticed that I was avoiding these vignettes and asked questions. I realized that despite the fact that I was uncomfortable opening the floor to that topic, religion is important to their identities. As expected, the vignettes brought many authentic responses and family stories about the Virgin of Guadalupe. These vignettes also allowed students who were not of Mexican heritage to contribute their family stories involving religion.

Responding to these two bilingual books had a long-lasting positive effect in our classroom as seen by students’ oral and written stories. A climate of acceptance and appreciation was established and the students felt a respect and value for their cultures that allowed them to continue to dig deeper into their family stories. They saw family stories as a valuable genre and continued to share these stories in varied contexts. For example, when asked to bring an artifact from home that had a memory, Victor brought a yellow monkey, named Bananas, which inspired this memory:

Bananas was made by my granddad. When my granddad died, he gave it to my dad. When I was born, my dad gave it to me. When I was two years old, I named him Bananas. Now I’m eight and I still sleep with him and I’ll always love him. When I grow up, I will give it to my son. If I have a daughter, I have Strawberry for her. Strawberry is a pink bear that my sister gave me. I just realized that I’m starting an heirloom.

Students gained an understanding that their young lives are full of rich memories and that writing their stories attaches value as well as saves and preserves these memories.

Our appreciation of multicultural literature continued through our year as we read more Latino books as well as books representing many cultures and parts of the world. We started juxtaposing international and multicultural literature with literature required by our curriculum, analyzing common themes, character development, settings, and conflict or tension.

Each week, when we visited the school library, a student would point to our librarian’s display of Garza books and we shared a “do you remember?” smile. For the student the smile meant, “Do you remember when we had so much fun with those books?” For me the smile meant, “Do you remember when a book was so powerful that it allowed a middle-aged Anglo teacher to gain a view inside of her students’ lives?”

References

- Ada, A.F. (2004). I love Saturdays y domingos. Ill. Elivia Savadier. New York: Aladdin.

- Lomas Garza, C. (2005). Family pictures/Cuadros de familia. San Francisco: Children’s Book Press.

- Lomas Garza, C. (2000). In my family/En mi familia. San Francisco: Children’s Book Press.

- Mora, P. (1997). Tomas and the library lady. Ill. Raul Colon. New York: Knopf.

- Soto, G. (1993). Too many tamales. Ill. Ed Martinez. New York: Putman.

Deanna Paiva teaches elementary school in Dallas, TX.

WOW Stories, Volume II, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesii1/.