Forging Connections: First Graders’ Responses to Multicultural Literature

By Karin Wright

As I work toward becoming a classroom teacher, I aspire to develop thought-provoking and meaningful curriculum, while also establishing a classroom climate that invites discussion and appreciation of diverse cultures. I aim to establish what Sleeter and Grant (1987) call “an education that is multicultural” for my future students, rather than presenting surface-level, isolated units of study about various cultures (Fox & Short, 2003). As a starting point for this quest, I visited a friend’s first grade classroom primarily to observe, but also to cultivate her students’ responses to multicultural texts. Using this group of first graders as a representative sample, I hoped to obtain baseline data to use when developing multicultural literature response engagements for my future classroom. I intended to provide the students with opportunities to encounter and respond to multicultural literature, and simply observe the results. As a visiting teacher with only limited time in the classroom, I planned to take on the role of observer rather than active teacher during each session, however, over the course of the project, my purpose changed somewhat so that I became more concerned with developing the students’ connection-making abilities.

As I began this project, I expected the students to skip over elements of culture within the texts, focusing instead on the similarities between characters and events in the stories and their own lives. This prediction stems from my experiences with first grade students who struggle to stretch their thinking beyond the familiar. In contrast, I also wondered whether students might focus only on the differences between the cultural representation in the texts and their own cultural experiences, missing elements of common humanity altogether. This prediction is related to the students’ young age and their assumed lack of experience with multiple cultures.

Context

I visited a neighborhood elementary school with approximately 450 kindergarten through fifth grade students in Tucson, Arizona. The school serves a community of middle and working class families, of primarily white European-American and Latino backgrounds, with a smaller percentage of students of Asian American, Native American and African American heritage. Of the 22 first graders with whom I worked, 13 are white, European-American students, eight are Latino students, and one is an African-American student. I conducted five weekly 60 to 90 minute sessions that consisted of a read-aloud followed by a response technique and a brief discussion. Each period was formatted as either a single whole group engagement, or multiple small group sessions. To evoke a variety of student responses, I put together a text set of four books that relate to the theme of cultural identity. According to Griffith (2008), “Text sets establish a framework for kids to expect connections to their own lives and to other literature and to develop strategies for making those connections.” By framing my inquiry as a text set study, I hoped to encourage the students to forge connections both between the texts and their own experiences, and among the texts themselves to build deeper understandings of the stories and their conceptions of the world.

Two of the books, I Love Saturdays y domingos (Ada, 2002) and Playing Lotería/El juego de la lotería (Colato Laínez, 2005), focus on Latino culture, while the other two, The Name Jar (Choi, 2005) and My Name is Yoon (Recorvits, 2003), describe Korean-American experiences. I chose these texts to encourage the students to build both obvious and less apparent relationships between stories. Additionally, I aimed to connect to the many Latino students in the class through the Latino texts, and also explore unfamiliar cultural experiences for all the students in the Korean-American books.

The students engaged in both graffiti boards, where groups of four or five students recorded their in-process thinking as I read aloud (Short & Harste, 1996), and in free response to write and/or draw their reactions and connections after each reading. The combination of small and large groups was intended to elicit different responses in different settings.

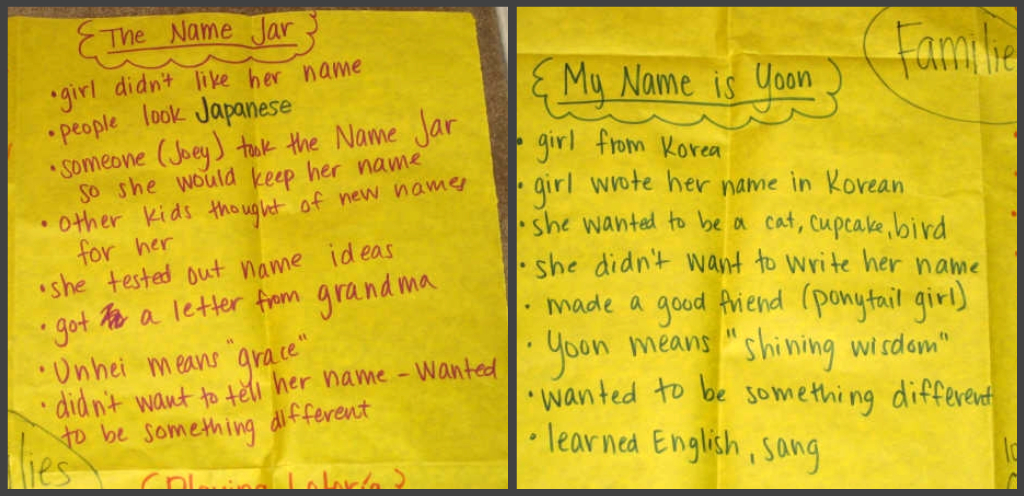

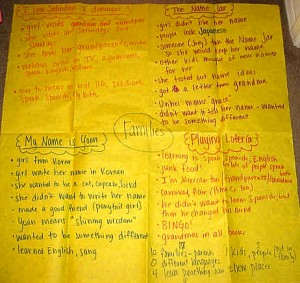

During the final two sessions, the students and I developed a chart to tie together the entire experience and to visually establish connections between the four texts. Griffith (2008) explains that students need “more than talk to explore the connections across books.” By listing the main points of each story, students were able to see similarities between all four books. In this way, “the text set encouraged [the students] to not look at literature in isolation but instead always in connection with other literature and their lives” (Griffith, 2008). Once this chart was complete, the students and I discussed major ideas that ran across all of the books to ultimately decide upon an over-arching theme for the text set. This pulled together all of our reading, thinking and discussing.

Children’s Responses to the Literature

Responding to I Love Saturdays y domingos

I read aloud I Love Saturdays y domingos (Ada, 2002) to the entire class and explained that the students would write and/or draw their thinking after enjoying the book. As I read, a few students commented on the use of Spanish in the text, saying that they knew some of the words and observing that the story was not entirely in English. After the reading, Ricky (note: all student names are pseudonyms), a Latino child, remarked that he is familiar with the Happy Birthday song in Spanish that is presented in the text because his family sings it. His classmates showed genuine interest in hearing the song, but Ricky appeared too shy to sing out loud.

The students then spent 20 minutes completing their responses on a blank piece of paper, and I asked each child to explain his or her ideas. Of the 19 participants that day, only two commented on a specific cultural aspect of language. One of those students was Ricky, who made a personal connection between the Happy Birthday song and the use of Spanish throughout the story to his own family experiences, saying, “This story made me think of the happy birthday song and it was Spanish and I know Spanish so does my grandma and grandpa and I love them.” Ricky connected to the language within the text, and his relationship with his grandparents from the main theme of the text. In this way, he was able to identify with the book from a specific cultural perspective and also connect to the universal concept of family bonds.

The majority of the students made connections between the plot of the text and their own experiences by commenting on family relationships, birthday celebrations, family events, and feelings of happiness. While these children successfully established text-to-self connections, none of them commented on the cultural elements of the main character’s family, experiences and identity. It appeared that the children were supporting my first prediction by focusing on universal human characteristics, rather than elements of unique cultures.

Two students responded to specific parts of the book: an illustration and the title. Robby drew and labeled when the main character is in her Abuelita’s garden with the dog. This was a minor event in the story and when asked to explain his thinking, Robby simply replied, “I liked this part.” Casey focused on the Spanish word domingos in the book title. He stated that this word reminds him of the word “donuts” through his writing and illustration. Though his understanding was a bit off-track, it is clear that Casey was attending to unfamiliar language and trying to make connections to words and concepts with which he is familiar.

After the first session, I noticed that the students were having some success with making connections to the story, however, the classroom teacher commented that the session made her aware of the need to provide her students with more opportunities for literature response. This comment, combined with my observations that many children made surface-level connections to the story, caused my focus to shift from pure observation of students’ responses to multicultural texts, to the development of students’ connections to texts more generally.

Responding to The Name Jar

In using the graffiti board technique, I worked with part of the class in three separate groups of four children. The students were to record their ideas while listening to The Name Jar (Choi, 2001), instead of waiting until the end of the story. In each of the small groups, a few children seemed unsure about responding during the read-aloud due to their lack of experience with this engagement. I assured the students that they should start responding as soon as an idea arose. Most of the children seemed excited about having ownership over the process, but a few still chose to wait until after the reading to begin their responses.

Each child described his or her response and answered questions to clarify their thinking. Of the 12 students I worked with on this day five made connections between the school experiences of the main character Unhei, and their own. The first graders identified with Unhei’s anxiety over going to a new school and making new friends, both universal childhood themes.

Three of the students commented on a major theme in the story — Unhei’s name. Mary wrote, “It makes me think of my name.” When asked to elaborate, she explained that Unhei does not like her name in the story, but she (Mary) likes her name because it is special. Katie wrote, “I think Unhei is a nice name. I’m glad that she kept her name.” Similarly, Nathan drew several children saying their names to another child and explained that everyone has their own, different name. These responses relate to the larger theme of cultural identity. The students connected with the idea that a person’s name is a part of what makes them unique and that names should be celebrated. Robby, Cara and Michelle illustrated the characters in the story, showing Unhei, her family members and her classmates. When asked to elaborate, they each explained that they drew the important people in the story.

I felt more confident that the students were increasing their understanding of connecting to texts and thinking more deeply about stories. The responses from Robby, Cara and Michelle showed that the students needed more practice to move beyond surface-level summaries and to begin thinking about the issues embedded in the stories.

Responding to My Name is Yoon

After introducing the first graders to texts that depict two very different cultures, I decided to support their connection-building by reading a book with more obvious similarities to the previously read The Name Jar. Before reading My Name is Yoon (Recorvits, 2003) to the whole group, I encouraged the class to think about their connections and wonderings as I read. In stark contrast to our first experience with free response, in which many children did not seem to know how to begin, the class appeared eager to respond. Again, the students spent 20 minutes working and I asked each child to describe his or her ideas once they finished. Of the 21 participants that day, eight made direct connections between My Name is Yoon and The Name Jar. These students commented on the similar pronunciations of Yoon and Unhei, the two characters’ similar appearances, their mutual desire to return to Korea, and their shared struggles to make friends in a new place. Three other students focused only on issues within My Name is Yoon, discussing Yoon’s difficulties with making friends, fitting in and feeling comfortable with herself. For example, Shawn wrote, “Yoon wanted to not be herself. Yoon wanted to be different things like a cat or a cupcake. Yoon has to be herself no matter what.” These two sets of responses demonstrate the students’ thinking about the over-arching themes of the two texts and their similarities.

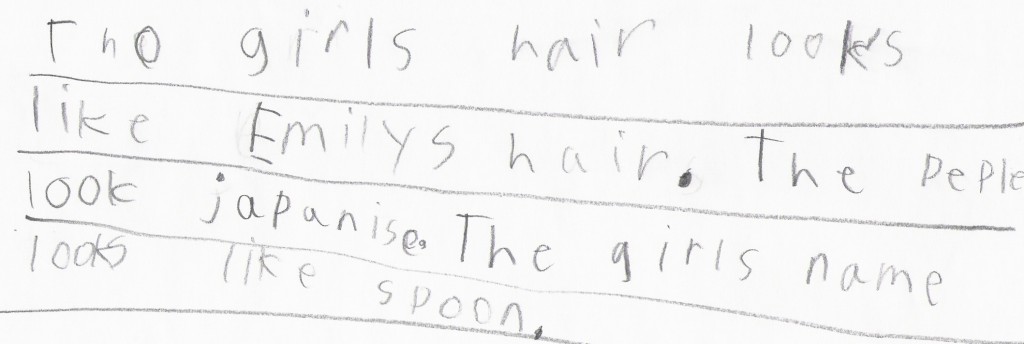

Four students made specific personal connections to the story. Ricky wrote, “This book made me think of when I was a little kid and I did not want to write my name because it all was scribbled.” Chloe commented that the story reminded her of the first day of school, while Emma connected Yoon’s experience of making a new friend to her own experience with her best friend, Chrissy. These children were able to identify with the characters and events in the book and view the story through the lens of their personal experiences. Three other students made connections to the text, but in a rather superficial way that did not address the underlying issues. Alex wrote, “Yoon made me hungry because she wanted to be a cupcake.” Casey commented that “the girl’s name looks like spoon.”

Casey also wrote that “the people look Japanese.” When asked why he thought so, Casey explained, “They just do their hair and eyes and stuff.”

Casey’s Free Response to My Name is Yoon

I prompted him to rethink this comment by asking where Yoon’s family originally came from. Casey recalled that they came from Korea, but was unable to make the connection that Yoon and her family are Korean, rather than “looking Japanese.” This was a cultural misconception that is likely due to Casey’s young age and lack of experience. It is also an instance when a reader’s initial understandings of a book are influenced by the previous knowledge they bring to the reading (Moreillon, 2003). Because Casey had a previously held conception of the physical attributes of Asian and Asian-American people, he was unable to see the relationship between Yoon’s homeland and her cultural identity. Despite this misconception, it was interesting that Casey was the first child to attempt to label the characters as part of a particular cultural group. Up to this point, no other student had used such language. Finally, three students responded by writing about and drawing events and characters from the story. These students remained on the surface with their responses by replicating parts of the text.

The variety of responses to My Name is Yoon demonstrated the students’ continuing development. Because several students connected two of the books, I was reassured that the class would engage in discussions about the similarities between all four books later on. At this point, there were still a few children whose ideas remained on a superficial level, but I felt encouraged that the majority of the students were pushing their ideas deeper to explore larger themes such as friendship, family, identity and a sense of belonging. Though there were still few references to the cultural elements of the stories, I realized I was no longer focused solely on exploring familiar and unfamiliar cultures with the students, but rather engaging the children in deep thinking about the books.

Continuing Responses to The Name Jar

In our fourth session, the remaining two groups (of five children each) participated in the graffiti board technique with The Name Jar. None of the students appeared reluctant to participate as some of the previous groups had. I attributed this to the students’ growing experience with literature response. Most students got right to work as I read, though a few children needed time to finish their ideas after the read-aloud. Again, each child shared his or her thinking at the end.

Of the ten participants, four students made personal connections to the story. Referring to the Korean nickname that Unhei gives to her friend, Christopher wrote, “It made me think of my friends because Chinku, that means friend.” These students continued to relate the experiences of the characters with their own to build a greater understanding of the events of the story.

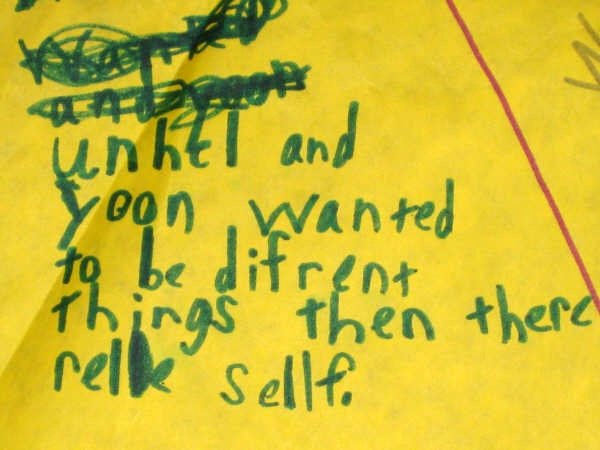

Seven students made text-to-text connections between The Name Jar and My Name is Yoon, just as their classmates had during the last session. The children were able to see both obvious and obscure similarities between the texts. Like the previous groups, the students commented on the similar sounding character names, and the girls’ similar appearances. Chrissy, Aaron and Mike all noted that the two girls were both from Korea, wanted to go back to their homeland and made new friends in the U.S. These observations demonstrated the students’ ability to relate different texts to one another and to uncover broad themes that they have in common. Shawn made a thoughtful conclusion when he wrote, “Unhei and Yoon wanted to be different things than their real self.” Shawn explained that both girls did not like their name and wanted to leave America to go back to Korea. He cited Yoon’s wish to be a cat, a bird and a cupcake and Unhei’s desire to change her name. This response was the most exciting to witness up to that point. It was clear that Shawn had been thinking deeply about each girl’s experiences and the meaning those experiences held for the characters. Not only was he able to recall several examples to support his idea, but he was able to pull together his thinking into a meaningful statement.

Shawn’s Graffiti Board Response demonstrates his developing ability to forge deep connections between texts

Once again, Casey wrote that “the people look Japanese” and added that their writing looks Egyptian. When asked to explain, Casey reiterated that the girls “look Japanese” because of their hair, clothing and eyes. He explained that Unhei’s name stamp has symbols instead of letters like “our writing.” I realized that Casey was, in fact, attending to cultural elements in the books, but they were surface-level and not especially significant to the overall meaning of the stories. Certainly, I was pleased that he was noticing ways in which the characters lives are different from his own, but I felt that by focusing solely on these concrete aspects of the stories, he was missing the deeper emotions and ideas. I made it my goal to encourage more student responses like Shawn’s thoughtful consideration of underlying themes rather than eliciting responses like Casey’s, which focused mostly on the details.

After the small group sessions, the entire class began pulling together our thinking about all of the books so far. We developed a chart highlighting the main ideas of each text. Initially, this engagement served to remind the students about each story, however as we discussed each text, students took notice of connections between the texts. By the time we got to My Name is Yoon, students were commenting that “both of the books have girls from Korea,” and “both of the girls wanted to be something different, so that should go in both boxes.”

Students pulled together their thinking across texts on comparison charts

These remarks demonstrated that the children were beginning to think about connections across all the books though they struggled somewhat with relating I Love Saturdays y domingos to the other two titles. I planned to present a final text that would support the students’ connections to I Love Saturdays y domingos and allow the children to see similarities across the entire text set.

Responding to Playing Lotería/El juego de la lotería

In our final session I read Playing Lotería/El juego de la lotería (Colato Laínez, 2005) to the whole group in order to revisit Latino culture and re-connect to our first text. To encourage students to think about their ideas during the read-aloud in preparation for the response time, the children were told that they had only five minutes to respond once the story was over. As I read Playing Lotería/El juego de la lotería, several students noted the use of Spanish within the text and its relation to I Love Saturdays y domingos. As opposed to previous sessions when only a few students made verbal connections during the read-aloud, this time nearly all of the children exclaimed things like “The game is like Bingo!” and “He’s learning Spanish!” The students were comfortable with the process of making connections to stories and stretching their thinking beyond the printed text.

After the read-aloud, the children had 30 seconds to gather their thoughts. I set a timer and they worked enthusiastically to record their ideas within the allotted five minutes. The students had one minute to share their thinking with a neighbor before I collected the responses. Of the 22 students, 12 made personal connections to the story. Six of these connected to the story’s setting by depicting students’ visits to fairs or carnivals. When asked to explain, most of these children described what fun they had at the fair, just like the boy in the story. Three children compared the lotería game to Bingo or another familiar game. The remaining three students connected the boy’s relationship with his grandmother to their own relationships with grandparents. The three topics of fairs, games and grandparents are universal concepts with which the children could identify, even though the fair and lotería game in the story are specific to Mexican culture and the grandmother asserts her cultural identity throughout the book.

Four students found similarities between Playing Lotería/El juego de la lotería and I Love Saturdays y domingos. Each of these connections focused on the use of Spanish in both texts and did not address the grandparent-grandchild relationship emphasized in each story. Two students wrote specifically about the interaction between the boy and his grandmother in terms of learning a language. Shawn wrote, “The boy taught his Abuela English and his Abuela taught him Spanish.” These students concentrated on the exchange between the English-speaking child and his Spanish-speaking grandmother and the way that their relationship helped them to share their cultural identities with one another.

Four Latino students made connections between their own cultural identities and the text. Chrissy wrote, “I’m Mexican too!” Ricky revisited his previous comments about his grandparents’ use of Spanish at home. “My grandma and my grandpa speak Spanish and I can understand them and so can my brothers and my mom and dad.” Andrew wrote, “I have the game lotería. My grandma taught me Spanish. Now I speak a little of Spanish.” Nathan explained that once he played a game similar to lotería with his family. All of these children were able to closely identify with the characters, events and culture presented in the story. Based on both their recorded and verbal responses, it is clear that these students felt proud to have a specific, personal connection to the book and to be able to share it. In these instances, the use of multicultural literature allowed the students to see their own cultural background reflected in a positive way within the classroom context. Other non-Latino students were interested in learning more about lotería, and turned to their classmates with firsthand knowledge of the game for more information. This made the Latino students feel valued as their cultural experiences were celebrated.

To conclude our final session, the students and I completed our chart and discussed the entire text set. When generating main ideas from Playing Lotería/El juego de la lotería, the students focused on text-to-text and text-to-self connections, as opposed to simply retelling the events of the story. Students noticed connections between Playing Lotería/El juego de la lotería and I Love Saturdays y domingos, and the discussion developed as students noticed similarities between books that were less obviously related. They discovered that Playing Lotería/El juego de la lotería, The Name Jar and My Name is Yoon all address the issue of learning something new and that all three books have characters who want to do something different and then change their minds in the end. They also noted that Playing Lotería/El juego de la lotería, The Name Jar and I Love Saturdays y domingos all highlight grandchild-grandparent relationships.

Class-generated chart highlighting major ideas and connections from the text set

After the discussion, the students brainstormed the following list of titles for the collection of books:

- Families

Different Languages

Learn Something New

Kids/People

New Places

We discussed each option to better understand how it reflects the “big ideas” of all the books. The list was reduced to “Families” and “Learn Something New” and then it was decided that the title of “Families” would be given to the entire text set.

Conclusions

Through this inquiry, I realized that not only must teachers introduce students to a multitude of cultures through literature, but we must also provide daily opportunities for thoughtful reflection about books. Because these first grade students did not have much previous experience with literature response, developing those habits and thought-processes became my primary objective.

My initial prediction was confirmed in that the majority of student responses focused on personal connections to the texts without regard for cultural issues, however, I came to see that young students can produce complex responses containing multiple layers of connections and thoughts about larger issues. I have always believed that primary students’ capabilities far exceed most adult expectations, and yet, I now realize that I expected the students to generate very simple ideas. As I reflected on each session, I often found it difficult to categorize the responses. With practice, the students expanded their thinking to frequently include personal and intertextual connections, and comments about deeper issues all within the same response. These multidimensional responses provided a great deal of insight into the students’ thought-processes and allowed me to track the development of their thinking over time.

Conducting this study made clear that it is not enough for a classroom teacher to expose students to a book and then leave it behind. While this may present an enjoyable experience for everyone involved, without the exploration of ideas within, between and beyond texts, students miss out on challenging and motivating processes that enable them to grow into more thoughtful and critical readers and thinkers.

Though my focus shifted from specific reactions to multicultural issues to the broader issue of literature responses, this inquiry has underscored the importance of developing an education that is multicultural from every angle. The students and I did not spend much time discussing the specific cultures within each text, but the issues remained visible and added to the students’ high interest level and consideration of large ideas. I feel even more strongly that all students have the right to a multicultural education that invites in-depth examination of both broad, universal themes and more specific cultural concerns. This establishes a safe and welcoming space in which students can explore challenging and complex issues together, to develop their understanding of literature and the world around them.

References

Ada, A. F. (2002). I love Saturdays y domingos. New York: Atheneum.

Choi, Y. (2001). The name jar. New York: Knopf.

Colato Laínez, C. (2005). Playing Lotería/El juego de la lotería. Flagstaff, AZ: Luna Rising.

Griffith, J. (2008). Making connections through text sets with young children. WOW Stories: Connections from the Classroom, 1 (2). Retrieved April 29, 2009, from http://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesi2/?page=13

Moreillon, J. (2003). The candle and the mirror: One author’s journey as an outsider. In D. Fox & K. Short (Eds.), Stories matter: The complexity of cultural authenticity in children’s literature (pp. 61-77). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Recorvits, H. (2003). My name is Yoon. New York: Frances Foster.

Short, K. G. & Fox, D. L. (2003). The complexity of cultural authenticity in children’s literature: Why the debates really matter. In D. Fox & K. Short (Eds.), Stories matter: The complexity of cultural authenticity in children’s literature (pp. 3-24). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Short, K. & Harste, J. (1996). Creating Classrooms for Authors and Inquirers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Karin Wright is a graduate student at the University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ.

WOW Stories, Volume II, Issue 2 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesii2/.