Transformative Practice: Multicultural Texts, Critical Literacy, and Student Choice

By Courtney Bauer

“I just don’t get how someone could treat another human being like that,” Jimmy wondered during our group discussion of a chapter from Survivors: True Stories of Children in the Holocaust (Zullo & Bovsun, 2004). The fourth-grade group sat in silence marveling at the significance of his words. Jimmy had said exactly what we all had been thinking, but were too afraid to discuss. How could seemingly normal people, who were considered your friends, turn on you in a matter of months and hand you over to the Nazi military police for an almost certain death? Seconds seemed like minutes and it was if the words were floating above us unattached to any reason or explanation.

After a minute Catherine piped up, “Yeah, why did the Nazis hate the Jews so much?” Other students nodded their heads. Looking back at the prologue of the book, I reread and summarized the first few pages. Political tensions at the end of World War I in Germany and the subsequent economic depression catalyzed anti-Semitic sentiment. Hitler believed that the Jews were responsible for Germany’s economic problems (Zullo & Bovsun, 2004). After defining some of the difficult vocabulary and providing background information about World War I, most of the students sat quietly with puzzled expressions on their faces. I finally told the class, “I don’t have an answer for you.” It was scary; the teacher didn’t really have an answer and neither did they. Searching for answers over the next two months, we did not anticipate that our exploration would end with more questions than answers, along with new understandings about tolerance, immigration, and the role of larger political and social systems in the lives of ordinary people.

The Context: Teacher/Researcher

As a teacher, critical thinking and questioning are my primary goals for students. For the past eighteen years, I have worked predominantly with urban, culturally diverse elementary students; many of whom already feel disconnected from school by the fourth grade. Concern for social justice and equity for all children led me to explore the tenets of critical literacy theory and read the sobering, yet inspirational, work of authors like Shirley Brice-Heath (1983), Lisa Delpit (2002), and Paulo Freire and Donald Macedo (1987). These researchers describe how schools, administrators, and teachers often view minority students, particularly those who speak alternative discourses, as language deficient and lacking the literacy skills or the exposure to be successful in school. Such assumptions and misconceptions trickle down insidiously into classroom practices in ways that can be emotionally and academically damaging and can prevent those who struggle as readers from successfully acquiring school literacies (Delpit, 2002; Compton-Lily, 2003). In addition, these readers often read less at home and school, have inadequate materials for reading at their level at school, and may only spend 20% of their day exposed to quality instruction in pull out programs outside of their regular classroom (Stanovich, 2004; Allington, 2007). Thus, the achievement gap continues to widen over the years between strong and struggling readers (Stanovich, 2004). Instead of schools building on students’ rich and varied home experiences and knowledge, many students are silenced, alienated, and feel under valued (Delpit, 2002).

In contrast, critical literacy, a pedagogy developed by Paulo Freire, foregrounds students’ local and personal knowledge and concerns while teaching academic literacy skills (Freire & Macedo, 1987; Shor, 1992). Resulting discussions, readings, and analyses of power inequities in the students’ world provide the impetus for social action to improve and better their world.

Critical literacy benefits all students (Freire & Macedo, 1987). Unlike more traditional interventions with struggling readers (such as teaching phonics skills in isolation), students are exposed to academic literacy strategies utilized for relevant and personal reasons. Benefits for readers from mainstream cultures include an opportunity to better understand culturally diverse perspectives and the agenda and motivation of those with and without power in our society. Consequently, students from all backgrounds can regain their voice, reconnect to school, and transform their identities into engaged, curious, and critical learners (Busching, 1999; Edelsky, 1999).

The Context: The Participants

During the 2009-2010 school year my fourth grade students varied in both ethnic backgrounds and socioeconomic status. Of the forty-three students enrolled in my three sections, twenty-one were White, eighteen were African American, eight were Hispanic, and one student was Asian. Forty-eight percent were classified as low socio-economic status and seven percent were Limited English Proficient. In addition, approximately ten students struggled on a variety of reading assessments, indicating that most of the ten were in danger of failing the state reading assessments.

Although many of the students needed differentiated instruction, critical literacy allowed students to make the connection between school literacy practices and individual power. In prior years, some of my most reluctant readers had reconnected to classroom discussions and texts through critical literacy activities. Eagerly sharing their knowledge, they realized their life experiences were valued and relevant to our readings. These connections transformed some of my students into active, engaged, and curious learners. Thus, I incorporated the tenets of critical literacy often during our whole group discussions due to the multitude of benefits for a wide variety of students.

Blending Theory and Practice

One of the biggest hurdles to fostering a critical curriculum is how to bridge theory into practice. Adapting materials and topics, yet following the mandated curriculum, has been an on-going challenge. Fortunately, this fall I stumbled upon two books full of examples and ideas, Making Justice Our Project edited by Edelsky (1999) and Creating Critical Classrooms by Lewison, Leland, and Harste (2008).

Making Justice Our Project (Edelsky, 1999) provides a description and examples of how to view texts through a critical lens while utilizing the tenets of whole language. Thus, a primary goal is to analyze underlying power relationships both in and outside of the classroom and how these relationships affect both personal and larger social issues relevant to the student. In order to move in this direction, the curriculum is centered upon, “books dealing with justice and injustice, social issues, and usually muted or absent voices,” (Edelsky, 1999, p.19). Thus, multicultural texts with themes of injustice are a natural curriculum choice. In addition, students can act to change these injustices.

Creating Critical Classrooms (Lewison, et al. 2008) provides lessons and themes to encourage students to question and consider multiple viewpoints in order to develop a critical stance. A practical model of critical literacy based on the work of Shannon (1995), Janks (2002), and Lewison, Flint, & Van Sluys (2002) is provided in the beginning chapters. In this model, students move between the social and the personal dimensions allowing the possibility “to create powerful, transformative curricula” (Lewison, et al., 2008, p. xxvii). Thus, students draw upon their personal resources and interests to drive the curricula and create opportunities for education that are relevant and powerful. I found that by using a combination of this model and guiding questions like, “Whose voice is heard? Whose voice is not heard?” my students responded with critical and deep conversations.

Thus, armed with these two resources and a wonderful classroom library, I began searching for multicultural texts that could provide the impetus for these types of discussions and subsequent actions.

Jumping In

The Holocaust is viewed as a topic typically for older children. I offered five multicultural titles related to our six-week theme: Hiroshima by Lawrence Yep (1996), Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes by Eleanor Coer (2004), Harvesting Hope: The Story of Cesar Chavez by Kathleen Krull (2003) In the Year of the Boar and Jackie Robinson by Bette Bao Lord (1986), and Survivors: Stories of Children from the Holocaust (Zullo & Bovsun, 2004). The students voted overwhelmingly for Survivors. Several reasons made this text a good choice. First, the students chose the text and took ownership of the topic. Second, my principal wanted more non-fiction incorporated into the reading curriculum. Third, according to our district’s curriculum planning guide for reading during the last six weeks, students should be reading texts in the basal reader on the theme of “Survival.” Therefore, this supplemental text connected to and would build upon their prior knowledge from our whole group readings. Lastly and most importantly, I knew that this particular book choice would inspire the students to question the Nazi government and allow for some deep, critical conversations about larger social systems.

Survivors: Stories of Children from the Holocaust contains a collection of narrative essays describing the personal accounts of children’s experiences during the Holocaust. We jumped right in with the first story, which describes the experience of Luncia, an eight-year-old Jewish girl living in Lvov, Poland. The least violent of all the accounts, Luncia lived in hiding with a German family until she was reunited with her parents and hidden in another home until the war was over. As Luncia describes an incident where she is nearly discovered by Nazi sympathizers, the students held their breaths and then let out a sigh of relief when she escaped. Soon students complained whenever I ended our daily readings. “Why can’t we read more?” was the constant request everyday. The students were hooked and so was I; we had to read more.

Questions followed about Jewish religion and culture. Most of my students knew little about Jewish culture and even less about World War II or the Holocaust. Most students only knew that Hitler was a “bad guy.” We started discussing what we knew as a group about Judaism, which was minimal. Fortunately, one Jewish student volunteered to describe many of his religious beliefs and traditions, allowing students to see how their lives connected to Jewish peoples. Because one of the most well liked students in the class was Jewish, the Nazi’s actions appeared even more atrocious. We also researched famous contemporary Jews and many students were surprised that many of their idols were Jewish. Although these beginning connections to Jewish culture and religion were important, I wanted the students to analyze the larger political and social systems that supported the mass genocide of Jews and apply this analysis to circumstances in their own world.

Recording Their Responses

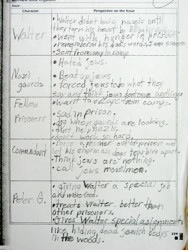

In an effort to extend the discussions, I asked the students to record their responses to our readings. Creating Critical Classrooms (Lewison, et al., 2008, p.229) provides concrete examples on how to guide students through this process. In the student samples below, I used the “Character Analysis” form to encourage students to consider all the different views of the main people in the story. Initially, students primarily described the characters’ actions and not their perspectives. In the box for the Nazi guard’s point of view (Figure 1), one student wrote, “They forced them to do what they say. beat the Jews.” These comments demonstrated literal knowledge and primarily described actions.

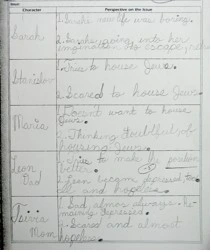

In an attempt to push beyond the surface, I had the students use tableau to “dig deeper into texts” (Lewison, et al., 2008, p.164). This drama activity took several class periods, but everyone was able to participate, including some of the children considered the most severely learning disabled. In groups of four, students chose one scene to depict from the book with each student portraying one character. The class as a whole tried to guess the scene from the book. Afterward the students explained who they were in the scene and their perspectives during the event. The students’ responses after the tableaux reflected a deeper analysis of their characters. For example, the second student in Figure 2 made statements like, “Scared to house the Jews" , and, “Scared and almost hopeless” . Thus through the group dramatization of pivotal moments in the text, the students were better able to explore and connect to the characters’ feelings and perspectives. Moreover, the students enjoyed this activity so much that they continually requested to use tableaux after all our readings.

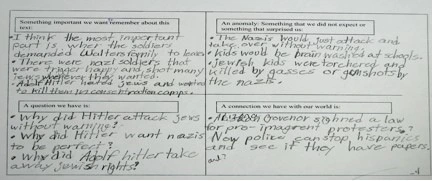

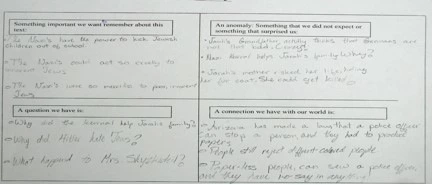

We also used a “Critical Reading” form from Lee Heffernan’s, Critical Literacy and Writer’s Workshop (2004) with critical questions that required students to describe what surprised them, share questions they still had about the text, and explain what events they thought were most memorable. Most students easily answered three of the four questions. However, when I first asked students about their connections to the events in the chapter, most of them could not name any. Nazi treatment of the Jews seemed isolated and disconnected to personal or governmental behavior they had experienced, but the combination of the events in the second chapter and a highly publicized current event changed all that.

Pivotal Moment: A Clear Connection

The second chapter describes Herbert Karliner’s experience in “Is There No Country in the Entire World That Will Take Us?” (Zullo & Bovsun, 2004). In 1938, terrorized by both soldiers and neighbors, Herbert’s family and many other Jewish families decide to flee Germany for Cuba on the S.S. St. Louis. When the ship docks in Cuba, the Cuban government refuses to allow entry to any passengers. Desperate and afraid, many consider jumping ship and entering illegally. Immediately, one student, Ignacio, interjected that his Dad did the same thing when he climbed through a barbed wire fence to cross the border from Mexico into the United States. Elan, an Ethiopian American student, declared that her uncle, who was caught in the war between Ethiopia and Eritrea, also had to escape to the United States to survive. Many of the students from recently immigrated families made personal connections that they had never shared.

Unfortunately, Herbert was not as lucky as my students’ families and the ship was forced to leave Cuba. The captain, a Jewish sympathizer, sent out a plea to every surrounding country to accept the passengers. In fact, a telegraph was sent to the First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt begging her to allow the children onboard into the U.S. Unfortunately, the American government denied the request, as well as the neighboring countries, forcing the Karliners and the other Jewish families to return to Europe. Students were shocked to discover that the United States had refused to take in the children.

Coincidentally, the same week we were reading about the Karliners, Jan Brewer, the governor of Arizona, signed the Arizona SB 1070 immigration law. During our weekly character classroom meeting, many of the Hispanic students heatedly discussed the injustice of this new law. Other students from diverse backgrounds agreed. How could policemen target Hispanics and request residency documents from them and not from others? Two African American students brought up the Rodney King beatings that we had discussed earlier in the year. What if the policemen starting acting like that? Students were outraged. At this critical moment, I asked the class if this event reminded them of anything else. After a short pause, hands quickly flew up and some excitedly shouted out the Nazis and the Jews. While students discussed some of the similarities, I offered the many differences between the German government and the U.S. government and laws. This conversation led to the perfect opportunity to discuss the protection of individual rights. We went back at the prologue and the last two chapters and discovered that the German government slowly took away the rights of Jews, beginning with the random stopping of Jews for identification. Although the students didn’t think that the intent of the Arizona governor was to hurt undocumented immigrants, they wondered how our own government could act so unfairly. Writing with intensity, the students wrote down their thoughts, this time with many connections. For example in Figures 3 and 4, the students comment in the connection box that police in Arizona can stop people who look Hispanic to check to see if they have papers.

Conclusion

This collection of responses was only the beginning. For our end of year research project many students chose topics related to the Holocaust. In addition, I brought up the creation of Japanese internment camps in the United States during the 1940’s. This led to a whole new unit of study. One of our primary texts was So Far from the Sea by Eve Bunting (1998). This fiction book describes the life of a Japanese American child in an internment camp. By this time, the students’ responses were much deeper and more sophisticated. Students wondered why the American government took away the rights of Japanese American citizens. In Figure 5, a student stated, “I learned it is important to remember important events even if they are not the most wonderful subject in the world. Sometimes you have to face the past and what has happened in the past.”

These conversations continued until the end of the year. At the beginning, I was unsure whether students would relate to the narratives or where we would end up on this journey. However, given the outstanding multicultural texts, student choice, and the guiding questions by Lewison, Leland & Harste (2008) and Heffernan (2004), the students moved from a superficial understanding of cultures and historical events to a deeper knowledge. Furthermore, learners analyzed these events critically and made many personal connections. Although in the end we did not act upon these injustices, I hope these students will have a heightened sensitivity to the protection of individual rights and the boundaries of the government, even if we never satisfactorily answered their questions about hatred between groups of people.

References

Allington, R. L. (2007). Intervention all day long: New hope for struggling readers. Voices from the Middle, 14(4), 7-14.

Brice-Heath, S. (1983). Ways with words: Language, life, and work in communities and classrooms. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Bunting, E. (1998). So far from the sea. Boston, Mass: Sandpiper.

Busching, B. (1999). Third class is more than a cruise-ship ticket. In C. Edelsky (Ed.), Making justice our project: Teachers working toward critical whole language practice (pp. 191-208). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Coer, E. (2004). Sadako and the thousand paper cranes. New York: Puffin.

Compton-Lilly, C. (2003). Reading families: The literate lives of urban children. New York: Teachers College Press.

Delpit, L. (2002). The skin that we speak. New York: The New Press.

Edelsky, C. (1999). On critical whole language practice. In C. Edelsky (Ed.), Making justice our project (pp.7-36). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Freire, P. & Macedo, D. (1987). Literacy: Reading the word and the world. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey.

Heffernan, L. (2004). Critical literacy and writer's workshop: Bringing purpose and passion to student writing. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Janks, H. (2002, November). Critical literacy: Deconstruction and reconstruction. Paper presented at the National Council of Teachers of English Annual Conference, Atlanta, GA.

Krull, K. (2003). Harvesting hope: The story of Cesar Chavez. Orlando, FL: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Lewison, M., Flint, A. S. & Van Sluys, K. (2002) Taking on critical literacy: The journey of newcomers and novices, Language Arts, (79), 382–392.

Lewison, M., Leland, C. & Harste, J. (2008). Creating critical classrooms: K-8 reading and writing with an edge. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Lord, B. (1986). In the year of the boar and Jackie Robinson. New York: Harper Trophy.

Shannon, P. (1995). Text, lies, & videotape: Stories about life, literacy, & learning. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Shor, I. (1992). Empowering education: Critical teaching for social change. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Stanovich, K. E. (2004). Matthew effects in reading: Some consequences of individual differences in the acquisition of literacy. In R. U. Ruddell, (Ed.), Theoretical models and processes of reading (Fifth ed., pp 454- 511). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Yep, L. (1996). Hiroshima. New York: Scholastic.

Zullo, A. & Bovsun, M. (2004). Survivors: True stories of children in the Holocaust. New York: Scholastic.

Courtney Bauer is a fourth grade reading and language arts teacher in Dallas, Texas. She is also a doctoral student at the University of North Texas.

WOW Stories, Volume III, Issue 2 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesiii2.