Enhancing Critical Visual Literacy through Illustrations in a Picturebook

Hee Young Kim and Angelica Serrano

Picturebooks are a primary tool for teachers in classrooms. A picturebook consists of verbal text and visual images in illustrations. Many research studies have explored the importance of illustrations in picturebooks and in visual literacy instruction (Nikolajeva, 2012, 2013; Painter, Martin & Unsworth, 2014; Serafini, 2010; Sipe, 1998a, 1998b). Illustrations are not just an extension of the text that reinforce the meaning of words, but are necessary for comprehension and understanding–reading illustrations is essential to make meaning of picturebooks (Galda & Short, 1993). Nikolajeva and Scott (2006) explored how verbal and visual text interplay and posit that the tensions between these two sets of signs create unlimited possibilities for word-image interaction. Salisbury and Styles (2012) explored the various aspects of visual images in picturebooks as a unique art form of visual literature. In this vein, the ability of reading images is essential. Visual literacy refers to the ability to construct meaning from visual images (Giorgis, et al., 1999). According to Bamford (2003), to be visually literate, a person should be able to interpret images to gain meaning and to analyze the syntax of images. Bang (2000) explored how the visual elements affect emotional response and developed principles of emotionally charged arrangements of shapes on a page to build powerful visual statements.

Illustrations and visual literacy have been studied as a way of going beyond print-focused literacy practices in reading picturebooks; however, incorporating visual literacy in developing culturally conscious understanding and critical pedagogy is often overlooked in classrooms. Critical visual literacy is the ability to investigate the sociocultural contexts of visual texts to illuminate power relations. Chung (2013) posits that critical visual literacy aims at encouraging students to critically negotiate meanings with visual (mis)representations by placing the text in a sociopolitical context. Our inquiry explored the way in which students engage in reading illustrations and examined how students interpret illustrations as a cultural text. The broader aim of this project was to build a critical visual literacy curriculum.

This inquiry specifically explored: (1) how explicit teaching and learning of the visual elements facilitates students’ engagement in responding to picturebooks; (2) how students negotiate their meaning making through the illustrations of picturebooks; and (3) how students investigate the embedded discourses in the illustrations of picturebooks through reading visual elements.

Research Context and Procedure

Hee Young Kim and Angelica Serrano are doctoral students who collaborated on this project. Angelica was teaching a combined classroom of third and fourth grade students at a local elementary school during the time of the study. The elementary school is located in the southwest of the U.S. Eighty nine percent of the students were Latino, four percent were Indigenous, four percent were White, and two percent were African American. Seventy nine percent of the students participated in a free or reduced lunch program. Hee Young visited Angelica’s classroom once a week for sixteen weeks.

This action research study combined critical visual literacy and reader response to create a semiotic approach to visual literacy instruction. The semiotic approach confronts the question of how images make meanings as signifying practice (Rose, 2016). Signifying practices refer to the meaning making behaviors in which people engage in following specific conventions or rules of construction and interpretation (Chandler, 2002). Just as with verbal signs, to be able to make meaning, knowledge of the basic grammar of syntax and semantics in visual signs is needed. According to Bamford (2003), the syntax of image refers to the pictorial structure and organization of visual elements (e.g. shapes, lines, colors). Visual semantics refers to the way images have meanings in the cultural process of communication.

After the instruction on visual elements, we read aloud a multicultural picturebook and students responded to the book. We examined how students used their learning of visual elements in their meaning making of this multicultural picturebook. We designed these experiences with the intention of deconstructing the notion of visual images as a creative art work and of providing an opportunity to see visual images as a meaning-making sign.

Instruction of Visual Elements

Art instruction in classrooms traditionally has focused on creative artistic ability, rather than approaching visual elements as signifiers. We designed visual art instruction based on three basic elements of visual image: color, shape, and comparison, and taught each element in one of the three sessions. We read picturebooks about the elements (Table 1) and discussed how each element represents emotions and ideas.

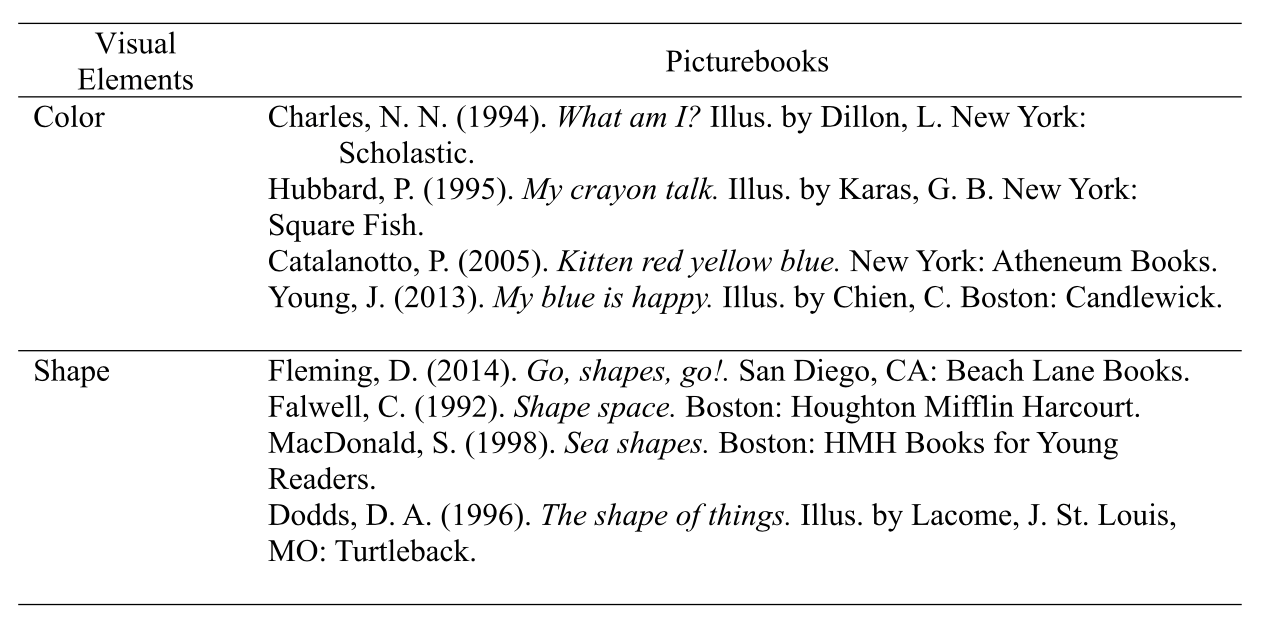

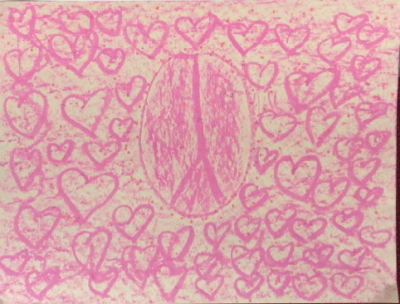

After reading these books, students explored their new learning. In one lesson, students chose one color to associate with meaning and drew pictures, Peggy (all names are pseudonyms) chose pink and drew images of hearts and peace. Ben chose blue and drew a scene of rain over the sea (Figure 1).

Figure 1a: Color

Figure 1b: Color

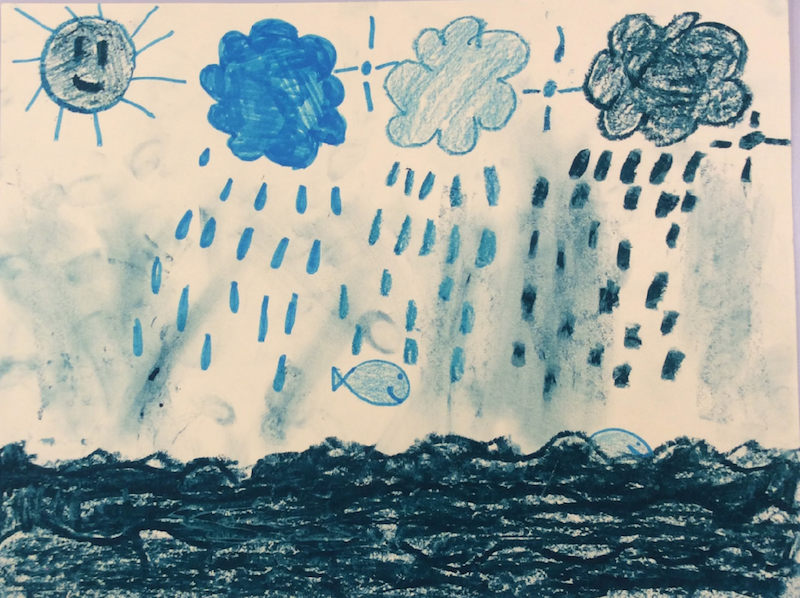

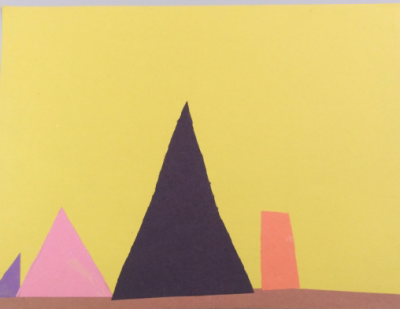

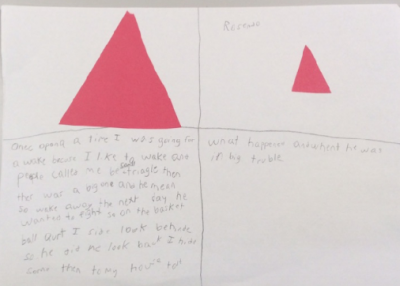

In the second lesson, we provided students with construction paper and scissors. Students cut various simple shapes of triangles, squares, and circles, and made a picture with those cut shapes (Figure 2).

Figure 2a: Shape

Figure 2b: Shape

In the third lesson students learned about comparison. Drawing on Bang’s (2000) book, Picture This, we showed students the comparison of big and small triangles and asked whom these two different size triangles can be associated. Students drew a T-chart and wrote descriptions of whom the two triangles might represent. Some students associated this comparison with a bully and a person being bullied. Others associated it with older and younger brother relationships. They associated the different sizes with power disparity (Figure 3).

Figure 3a

Figure 3b

Next, we showed them another example of comparison using sharp pointed lines and rounded lines. We asked students how these lines felt different. They said that the pointy line was scary and the rounded line was calm and smooth. After our discussion, they drew a T-chart and made an image using sharp and rounded lines along with writing a description (Figure 4).

Figure 4a: Comparison of Line

Figure 4b: Comparison of Line

During this lesson, we primarily used construction paper rather than drawing or painting. We hoped that through these activities students would gain an analytical stance toward visual images.

Response to a Multicultural Picturebook

After learning about visual elements, we read aloud Smoky Night written by Eve Bunting and illustrated by David Diaz (1994). Daniel, an African American boy, lives with his mother in Los Angeles during the racially charged 1992 riots. In his community, Mrs. Kim, a Korean American, runs a grocery store. Daniel’s family and Mrs. Kim do not get along with each other, however, they come to think that they should know each other when they observe their pet cats putting their differences aside.

We selected Smoky Night for this study for its socio-historical portrayal of the Los Angeles Riots in 1992, given that this study uses a critical approach to explore the historical, cultural, and ideological lines of authority that underlie social conditions (Sensoy & DiAngelo, 2011). Secondly, this book was awarded the Caldecott Medal in 1995, which can be regarded as verification of the quality of the illustrations.

Sociohistorical Context of Smoky Night

Smoky Night is set during the L.A. Riots, when a jury acquitted four L.A. police officers in the beating of Rodney King during his arrest for a traffic violation in 1991. A video of King, an African American, being beaten by four white L.A. policemen circulated throughout the media. The video, along with the LAPD’s history of brutality and racial injustice fueled six days of rioting that left 63 people dead, 2383 people injured and an estimated $1 billion dollars in property damages in areas including Koreatown, where 90% of the facilities were ruined (Lee, 2015).

A few weeks after the King incident, while the video of King’s beating was widely being broadcasted and African Americans were protesting police brutality, Latasha Harlins, an African American girl, was shot by a Korean American grocery store owner, Soon Ja Du, during an altercation in the store. Du claimed self-defense and gave security video to the LAPD, hoping that the security video would vindicate her claim. The LAPD announced they were pursing Du’s actions as “Murder One”, and released the videotape to the media. The media edited the video to show only the scene of Du shooting an unarmed African American girl, leading some to believe that the LAPD wanted to replace the brutal imagery of the Rodney King beating with the image of a Korean American merchant killing an African American girl (Romero, 2012).

This shooting by a Korean American merchant was not forgotten during the riots a few weeks later and many businesses in Koreatown were the target of looting and vandalism. Witnesses to the riots claim that the LAPD did not defend Korean-American business owners and allowed their businesses to burn (Lah, 2017).

This history informed our decision to explore a critical reading of the book through the visual images with students. We read aloud Smoky Night to students and showed each illustration so they could appreciate Diaz’s artwork along with verbal text. On page four, we read aloud only the verbal text and did not show students the illustration. Instead, we asked students to draw their own illustration for the verbal text.

Through our content analysis of the book, we thought that this illustration was problematic. The verbal text describes the scene of rioting at Mrs. Kim’s market, along with descriptions of the difficult relationship between Daniel’s family and Mrs. Kim. In the illustration, Mrs. Kim is drawn in the center in a large size, holding her hands up. Rioters are visible with only part of their bodies, hands and nose and mouth, at the edge of the illustration. Mrs. Kim, in contrast, is depicted as a scary angry person. Her arms are depicted disproportionately large. Contextually, the rioters are African American and Mrs. Kim is Korean American. However, interestingly, only Mrs. Kim is depicted with thick black hair, while the African Americans characters in the previous pages such as the rioters, Daniel, and his mother, have brown hair. Mrs. Kim has red eyes, which are never Korean racial traits. According to Omi and Winant (2016), who acknowledge the instability and socially constructed characteristics of race, there is a crucial corporeal dimension to the race-concept. Race is ocular in an irreducible way and is a concept that signifies and symbolizes social conflicts and interests by referring to different types of human bodies. In Smoky Night, this way of depicting phenotypes seems arbitrary. Mrs. Kim is portrayed with physical characteristics which are exploited to make her appear scarier than the rioters and protestors.

After students drew their own pictures, each student showed his/her picture to the whole class. For this whole group sharing we used a response engagement “Save the Last Word for Me” (Short, Harste & Burke, 1996), which aims to facilitate readers’ active reading by encouraging multiple interpretations of a particular visual image. An active stance in reading is facilitated by asking questions and looking for points of agreement or disagreement with other interpretations (Short, Harste, & Burke, 1996). Each student showed his/her drawing without commenting while other students stated what they thought that student’s picture signified. After listening to other students’ interpretations, the student who drew the picture said what each visual element in his/her drawing meant.

After students had shared their drawings, we showed them the illustration from page four of the book. Students were surprised by the illustration. Students discussed and wrote about how their understanding changed before and after they saw the illustration. After we finished reading the remainder of the book, we discussed the whole story. In addition, some of the students participated in interviews. We examined students’ pictures and comments to explore the ways in which they were using visual elements to consider meaning.

Use Visual Elements as Signs for Meaning Making

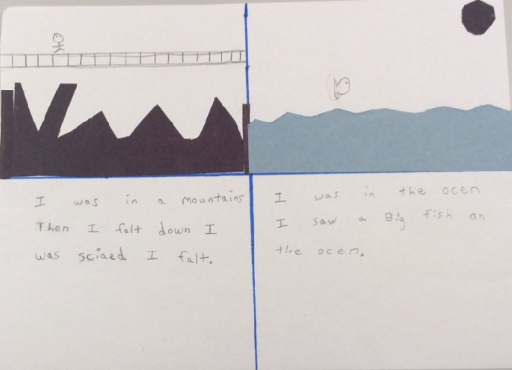

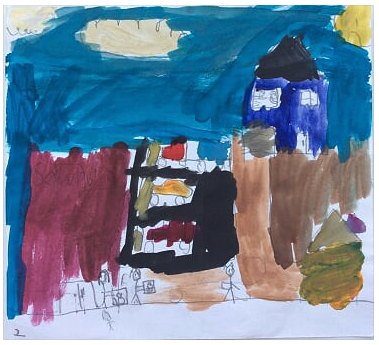

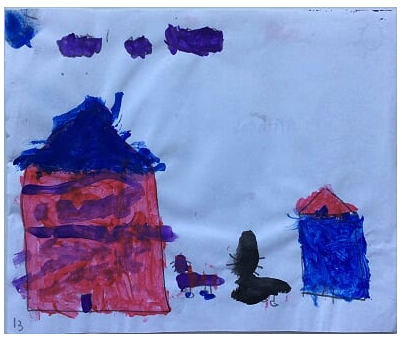

More than half of the students drew illustrations in a realistic style. They drew visual images that were similar to real objects (Figure 5). Seven out of eighteen students represented their interpretation of the verbal text in semiotic ways using simple shapes and color. Students who used simple shapes in their drawings provided clear explanations about what their visual signs signified. Ben drew two big black triangles, which are as big as a three-story building (Figure 6). Ben said the triangles were stealers. He said that they were bad and scary people so he used black and drew them as big pointed triangles. Andy drew two houses with red and blue shapes of a triangle and a square (Figure 7). Andy stated that he used primary colors to show that Mrs. Kim and Daniel’s family do not get along with each other. While Andy was drawing, I asked him whether he liked drawing. He said that he was not good at drawing, so he did not enjoy drawing, but he could draw at least triangles and squares so now it was fun.

Through our explicit instruction about visual elements, students took a new perspective on visual images as a meaning signifying process and so more actively engaged in learning and meaning making. Isabella drew two cats (Figure 7). She depicted two cats with profiles, confronting each other. While most students drew pictures to show what happened, she focused on the theme of difference and conflict relationships. She represented the theme by drawing the cat’s faces with different colors and placing them in a confrontational position.

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Negotiation of Meaning Making through Illustration

Nikolajeva and Scott (2000) delineated the various interplays between verbal and visual texts in picturebooks, arguing that counterpoint interaction of verbal text and illustrations can provide alternative information and contradiction between text and image. Through this characteristic, readers can be introduced to different interpretations of the event narrated by verbal text. This was the case when we showed students the illustration on page four of Smoky Night after they drew their own pictures. Students discussed and wrote the reason for their astonishment, comparing their meaning making before and after they saw the illustration.

Social Context vs. Personalization

After listening to the verbal text, but before he saw the illustration, Luke said that he thought about the event of stealing. He was making meaning about the place where the rioting happened and drew the background of place. However, when we showed the illustration, he was astonished by what he saw and started to think about Mrs. Kim. This switch of attention to Mrs. Kim was not only the case for Luke, but for most students. After we collected students’ drawings, we categorized them according to the theme they represented. Eight students drew about the background of place by drawing rows of stores, roads, cars, and small sized people. Five students focused more on the act of stealing. For example, one showed two big people carrying big bags, presumably filled with items from looting. Four students focused on conflict by drawing the confrontation between the two cats. Students’ visual interpretations of the verbal text were about where the event happened, what the event was, and how the relationship between characters developed. Conversely, the illustration in the book focuses on Mrs. Kim by positioning her whole body in a large size at the center of the page. None of students focused on Mrs. Kim. No one interpreted the verbal text as indicating the importance of Mrs. Kim. After students saw the illustration, they came to think about who Mrs. Kim was and how she looked.

Being Scared vs. Being a Scary Person

When we showed the illustration, most said that they were astonished. When we asked why they were astonished, students said that it was because Mrs. Kim looked very scary, commenting that they had not considered Mrs. Kim to be a scary person. Sarah wrote about her changed interpretation of Mrs. Kim before and after she saw the illustration.

Before: I thought Mrs. Kim was going to be sad and do nothing but yell.

After: She is big tall scary looking and angry. Her arms are up. She yelling and she look a lot different.

Sarah explicitly stated that the reason why she changed her interpretation of Mrs. Kim was because of Mrs. Kim’s visual posture in the illustration. Jasmine also wrote that “because Mrs. Kim was [should be] inside. She is sad, not angry just sad.” Jasmine said the reason that Mrs. Kim is inside was because she was scared of rioters, so she must have stayed inside the building. After Jasmin saw the illustration, she changed interpretation to “she looks mad, angry.”

Critical Examination of Racialization

After the close reading session of the text and the visual image on page four, we read aloud the rest of book. Students used their developing ability of looking at visual elements as they responded to the rest of the book. This analytic ability encouraged students to look at the illustrations from a critical stance. They started to make inferences about the embedded racialization in the depiction of Mrs. Kim in the illustrations.

Students pointed at the color used in the depiction of Mrs. Kim and associated it with racial injustice. Many students pointed out that Mrs. Kim’s skin and hair color was dark. Sandy said that Mrs. Kim’s “black puffy hair looks scary”, and “It will be calm. If Mrs. Kim was white, she won’t be that scary.” Students also pointed out that on page four when Mrs. Kim got angry and mad, her skin color was black, but at the end of the book when all the conflicts are resolved, her skin color turns to be whiter than any other characters’ skin. Students clarified that the black color of the skin was associated with anger and madness, while the white skin color was associated with peace and happiness. We could see that students noticed that the factors that made Mrs. Kim appear scary were mainly connected to how the physical characteristics of Mrs. Kim were illustrated. Through being visually literate, students could clearly state the racialized discourse in which corporal traits associated with emotions of anger and scariness, which are naturalized and embedded, but were scarcely being discussed.

Reading visual elements was a useful tool for students to explore the embedded discourses of the book. Students made their own inferences and provided evidence for their inference by stating their visual analysis. Robin said during the interview;

“[I am] kind of sad, but it’s being mean to Mrs. Kim, because they are putting, look, because in this picture, I can really see. Look. Kim, because they are putting all of these people with one color and she’s in the back (pointing to another page). She has different color. That’s being mean to Mrs. Kim. Just because she is different color doesn’t mean that you have to treat her that way. They didn’t like Mrs. Kim because she has another color. In this story, they treat her bad.”

By exploring the illustration based on their knowledge of visual elements with strong agency and critical discourses, students adopted critical and active stances in responding to the book. Although who “they” are was not clearly stated during his interview, we could see that Robin was taking an active critical stance to the way Mrs. Kim was depicted by the illustrator and/or treated by other characters.

Conclusion

Picturebooks bring together two different sign systems–verbal text and visual images. Consequently, the ability to read illustrations is crucial to understanding any picturebook. In this study, instruction in meaning-making through visual elements facilitated students’ engagement in responding to picturebooks and students came to understand reading visual images as a meaning making practice. They represented their responses to the verbal text with visual images and clearly stated the meaning of each visual element. Visual literacy was a useful approach to help students take a critical stance in understanding picturebooks. Visual literacy enabled students to provide explicit reasoning for their understandings and interpretations so that they were able to have agency in their meaning making strategies.

References

Bamford, A. (2003). The visual literacy white paper. Retrieved from http://wwwimages.adobe.com/content/dam/Adobe/en/education/pdfs/visual-literacy-wp.pdf

Bang, M. (2000). Picture this: How pictures work. San Francisco: Chronicle.

Bunting, E. (1994). Smoky night. Ill. D. Diaz. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Chandler, D. (2002). Semiotics the basics. New York: Rutledge.

Chung, S. K. (2013). Critical visual literacy. The International Journal of Arts Education, 2013, 1-21.

Galda, L., & Short, K. G. (1993). Visual literacy: Exploring art and illustration in children’s books. The Reading Teacher, 46(6), 506-516.

Giorgis, C., Johnson, N. J., Bonomo, A., Colbert, C., Conner, A., Kauffman, G., & Kulesza, D. (1999). Visual literacy. The Reading Teacher, 43(2), 146-53.

Lah, K. (2017, April 29). The LA riots were a rude awakening for Korean-Americans. CNN. Retrieved from http://www.cnn.com/2017/04/28/us/la-riots-korean-americans/

Lee, S. (2015). Asian Americans and the 1992 Los Angeles riots/uprising. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History. Retrieved from http://americanhistory.oxfordre.com

Nikolajeva, M., & Scott, C. (2006). How picturebooks work. New York: Rutledge

Nikolajeva, M. (2012). Reading other people’s minds through word and image. Children’s Literature in Education, 43, 273–291.

Nikolajeva, M. (2013). Picturebooks and emotional literacy. The Reading Teacher, 67(4), 249–254.

Painter, C., Martin, J., & Unsworth, L. (2014). Reading visual narratives. Bristol, UK: Equinox.

Romero, D. (2012, April 26). L.A. riots: LAPD tried to displace its racism problem and ‘put it on a Korean merchant’, says former Times reporter John Lee. LA Weekly News. Retrieved from http://www.laweekly.com/news/la-riots-lapd-tried-to-displace-its-racism-problem-and-put-it-on-a-korean-merchant-says-former-times-reporter-john-lee-2391941

Rose, G. (2016). Visual methodologies (4th ed.). London: Sage.

Salisbury, M., & Styles, M. (2012). Children’s picturebooks. London: Laurence King.

Sensoy, O., & DiAngelo, R. (2011). Is everyone really equal? New York: Teachers College Press.

Serafini, F. (2010). Reading multimodal texts: Perceptual, structural, and ideological perspectives. Children’s Literature in Education, 41, 85-104.

Short, K. G., Harste J. C., & Burke, C. (1996). Creating classrooms for authors and inquirers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Sipe, L. (1998a). How picturebooks work: A semiotically framed theory of text-picture relationship. Children’s Literature in Education, 29(2), 97-108.

Sipe, L. (1998b). Learning the language of picturebooks. Journal of Children’s Literature, 24(2), 66-75.

Hee Young Kim is a doctoral student at the University of Arizona in Tucson, Arizona and a former classroom teacher from Korea.

Angelica Serrano is a doctoral student in the department of Teaching, Learning and Sociocultural Studies at the University of Arizona and a classroom teacher in Tucson, Arizona.

WOW Stories, Volume V, Issue 3 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at http://wowlit.org/wow-stories-volume-v-issue-3/.