Childhood & Politics: Children's Historical Fiction set in the Soviet Union

“President Putin."

“The Cold War.”

“James Bond, 007!”

“Gymnastics.”

These are response from my students when asked what they know about Russia. Their knowledge about Russia is based on recent events with typical historical Hollywood representations: James Bond, ever loyal to the crown, outwits Russian villains whose language is mostly understood through film subtitles. Because they were born in the late 80’s and early 90’s in the U. S., their images of Russia are much different from my recollections. Let's look at, then, some historical fiction that depicts children’s physical and emotional resilience during Stalin’s ideological and tyrannical rule.

Let me preface the discussion, first, with my own literary connections. When I was in school, basic and simple information was taught as “common knowledge.” For instance, Columbus was a remarkably great explorer whose biographies were “must reads.” The Soviet Union was instrumental in the division of Korea and was actively involved in the North’s adoption of communism. Historically, Russia has been critically involved with Korea, often in negative ways as participants in the Chinese and Russian War in 1658, the war between Russia and Japan in 1904 and 1905, and the siding with North Korea in the early 1950’s. While frequently referred to in Korean history, there was seldom much chance to read U. S. children’s literature about Russian history and the communist revolution. As my students’ noted Russia was, for Hollywood, the official U. S. foil and global villain (sometimes, North Korea played that role as well), it didn’t appear that way in children’s literature. In comparison, Germany's brush with ideological rigidity in the Hitler Youth, the SS (Schutzstaffel), and the Holocaust have been much more literarily accessible. Often, Russia appears as an ancillary topic in these texts much like Canada does in Underground Railway stories.

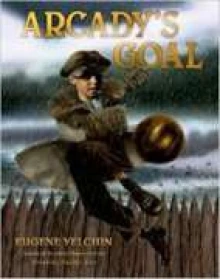

Between Shades of Gray (Sepetys, 2011) has earned major recognition since its publication. The story is told from the perspective of a Lithuanian girl in 1941 who was deported to a Siberian work camp with its extreme deprivations. The camp served as a literary metaphor for the harshness of the Stalin regime. The overall familiarity that readers have with WWII served as a natural bridge for this story with a different setting. After Between Shades of Gray came Breaking Stalin’s Nose (Yelchin, 2011) and Arcady’s Goal (Yelchin, 2014). Breaking Stalin’s Nose has the same "feel" as Red Scarf Girl by Ji-li Jiang (1998), but for younger audiences. Red Scarf Girl was set during the Chinese Cultural Revolution and, in that sense, parallels Eugene Yelchin’s two books set during Stalin’s reign of terror. As a sub theme, I want to focus on childhood under communism.

In Breaking Stalin’s Nose, the protagonist, Sasha wants to join the Soviet Young Pioneers. Sasha’s father is a well-respected party member and Sasha reveres Stalin as almost god-like. When Sasha’s father is arrested as an enemy of the people, Sasha’s social status in school is also jeopardized. Yet, he never doubts that Stalin will rescue him and restore their families standing in the party, “Tomorrow everything will be better. Tomorrow Stalin will rescue my dad. Tomorrow I will be a Pioneer” (p. 45). Just to complicate matters, Sasha accidentally breaks the nose off of a statue of Stalin. Concerned about being punished for “breaking Stalin’s nose,” Sasha stands silently while others are accused and deported to prison. When one of his Jewish peers is deported he gradually realizes that what he sees and believes about Stalin and the Soviet State may not be true.

In Breaking Stalin’s Nose, young readers experience the terror of total state control, allowing ideological rigidity to rationalize injustices and sufferings. Reflecting back on my childhood, it seems possible that the way communism was portrayed allowed children to easily categorize people into either enemies or heroes. It would be very believable for children, in that environment, to wait for their political heroes to emerge victorious. Sasha says, “The State Security is our secret police, and their job is to unmask the disguised enemies infiltrating our borders” (p.10). Stalin’s words morph into hope as a certainty: “Stalin says that sharing our living space teaches us to think as communist “WE” instead of capitalist “(p.8).

Bullying, too, is used as a tool to control children, maximizing the fear of being labeled an “enemy of the people.” “Four-Eyes is Borka Finkelstein, the only Jewish kid in our class. His parents were arrested at the beginning of the year and now he lives with his relatives. We call him Four-Eyes because he wears eyeglasses. Anybody who’s not a worker or a peasant and reads a lot we call Four-Eyes.” (p.49). It continues in Arcady’s Goal (Yelchin, 2014), a story about an adopted orphan whose new father encourages him to play soccer. Arcady is a talented soccer player and he supports Arcady by creating a soccer team. However, other soccer team members resist playing with Arcady because he is from an orphanage that accepts many children whose parents were enemies of the people, i.e. German fascists. Arcady, of course, is frustrated with it all, “I am not interested in politics, so I walk away. Politics has nothing to do with me. I came here to play soccer “(p.116).

These two books invite readers to move past prejudicial communist contexts and look at the detailed dynamics of children’s peer cultures. Despite the pervasiveness of propaganda and the focus on nationalism in these stories, the innocence and naiveté of childhood was also present. Despite the best attempts of the Communist system to manipulate every aspect of childhood, these stories show the resilience children possess, even when what they believed so fiercely evaporates with reality.

Next week, I will continue with a Russian picture book which emanated from and was improved by the propaganda movement. I will also look at the birth of the Soviet state regime with Candace Fleming’s Family Romanov (2014).

Journey through Worlds of Words during our open reading hours: Monday-Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit archival stream.

After reading this blog, I looked back my book list. "Breaking Stalin’s Nose" was one of the books included in my list under the theme of "power and dominance and political persecution". I found that I had included "Red scarf girl" under the theme too. When I was reading "Breaking Stalin’s Nose", I also had the "feelings" that I got when reading "red scarf girl", in terms of peer relationship and culture, how they survive at school and community, and their family relationships etc.

Russia is the country that I don't really know about. In Japan, I learned a little about their history and long historical relationship with Japan. When I was thinking about Russia, I came up with Hitler and enemy of America.... I found that I don't know very well about the country and contemporary life styles of Russian people..