Indigenous Own Voices after Sherman Alexie

I grew up on a steady diet of Island of the Blue Dolphins, Little House on the Prairie, Walk Two Moons, Julie of the Wolves, et cetera, stories with native content written by non-native authors. Before The Absolutely True Diary of a Part Time Indian, I hadn't read Cynthia Leitich Smith's or Joseph Bruchac's novels. But I had read Michael Dorris' and Lousie Erdrich's work for children, thanks to my love affair with Erdrich's novels for adults. I hadn't read any Indigenous Canadian authors writing for youth. Before The Absolutely True Diary of a Part Time Indian, I offered my students and my children solely historical fiction about Indigenous identities and stories. Nothing contemporary, and so very little, sadly, Indigenous Own Voices.

When my (Hopi/Tewa/Sioux) daughter first read The Absolutely True Diary, it was the summer between sixth and seventh grades. She told me she had never seen herself in a book before and I scoffed. From my non-Indigenous perspective, I gave her all the books I could find with Indigenous content. I was aware of the importance of cultural representation in literature. I actively sought high-quality Indigenous literature for her. But I hadn't noticed the enormous gap in my choices. I gave her traditional and historical stories, so Alexie's novel resonated with her like nothing she had ever experienced. I was embarrassed. But, also, I was activated. I have worked, since that day, to increase awareness of Indigenous #ownvoices literature for youth, to advocate for Indigenous youth whose school curricula woefully lack in cultural representation and to help support the educations of a new generation of potential Indigenous #ownvoices authors and illustrators.

When I taught English at a reservation high school, we read two whole class novels, The Absolutely True Diary by Sherman Alexie and The Round House by Louise Erdrich. The rest of our reading menu was populated by a long list of primarily Indigenous authors, thanks to two very successful Donors' Choose fundraising drives. My students loved Joseph Bruchac, Erica Wurth, Richard Van Camp, Ruby Slipperjack, Beatrice Mosionier, Cynthia Leitich Smith, Tim Tingle and others. They had access to an array of North American Indigenous authors. I made sure there was no single story of Indigeneity in my classroom.

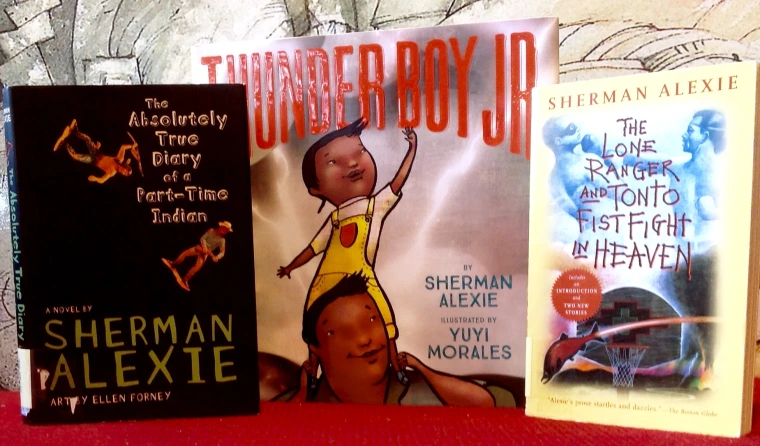

However, when a group of students convened in March in preparation for a panel about Indigenous young adult literature at the Tucson Festival of Books, I asked them if they had a favorite book. One student said Blasphemy, another The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven, the next student said The Absolutely True Diary of a Part Time Indian, another student said Reservation Blues. Each of these books was written by Sherman Alexie.

This conversation occurred just a few weeks after Alexie addressed the sexual misconduct accusations levied against him by a number of women and just a week after some of these women came forward telling their stories. "There are women telling the truth," Alexie said in a statement. My students hadn't heard the accusations yet; they hadn't heard the women's stories. So I told them, and I asked how they felt about this information. "What should we do, now?" I asked.

They discussed separating the art from the artist, one of the common reactions to the #metoo stories circulating around the creative world. My immediate reaction was to defend those who were removing Alexie's books from their shelves, removing his name from their scholarships and awards, turning to other Indigenous authors instead. Why support Alexie financially by purchasing his books when a large part of the stories surfacing has to do with him stifling the careers of Indigenous women writers, using his power to manipulate them, harming their careers?

Yet, here is where I am stuck. These students were exposed to many other Indigenous writers, and yet Alexie remained their favorite. Why? They said over and over that they related to the characters, the situations, the humor. They felt a kind of ownership of Alexie's stories that they did not feel with other writers. Perhaps this is because most of them were introduced to Indigenous fiction first through Alexie, either The Absolutely True Diary of a Part Time Indian or the film Smoke Signals. Perhaps this initial love affair with a kind of fictional storytelling that they relate to is too strong to give up on. So much is taken away from Native youth. I can't take this away, too.

But many are adamant about the importance of removing Alexie from reading lists. I worry about what might happen if teachers and districts have The Absolutely True Diary of a Part Time Indian in their class sets. I worry that there aren't other class sets of #ownvoices Native authors currently on those school shelves and that the funding and/or motivation isn't there for replacement. I worry that, aside from Alexie, Indigenous content is solely traditional and historical, only for Thanksgiving units, only the racism of the Little House series, only written by white authors. I worry that if we remove Alexie from these district and class sets, then there will not be a strong enough push to replace this one view of contemporary Native youth with any other texts, and any stories about contemporary Native youth will disappear into the mists of the history textbook. If Alexie is currently the (unfortunately) single story of Indigenous youth in many schools, what happens if we subtract his works from the classroom and the single story becomes no story at all? Where will the Indigenous young people in those classrooms see themselves reflected in the literature? Where will the non-Indigenous kids learn vital stories to combat the negative and inaccurate information about Native America they have been subject to all along?

That being said, a better version of this problem is that teachers and librarians and curriculum creators and parents and the youth themselves seek out a diversity of Indigenous authors. This is possible, but it is something we must fight for, fundraise for and advocate for.

In the coming weeks of WOW Currents, I focus on exploring Indigenous literature for children and young adults.

Journey through Worlds of Words during our open reading hours: Monday-Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturday, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m.

I believe young people are wise enough to appreciate quality literature. Shame is Alexis is banned from the classroom; as you suggest, many more authors plus himself should make up the bibliography list for these youngsters.

As a white teacher of literature, I always have this discussion with my classes when we read anything by Alexie. With seven years to reflect, do you still teach his work?