2025 Trends in K-12 Global Literature

Each year, we report the annual trends in global literature for young people after updating the annual global recommended reading lists. These lists consist of books published and/or distributed in the U.S. between July 2024 and July 2025. What is interesting this year is that the major trend is the lack of dominant trends in themes, topics, genres and countries.

The updated K-12 global recommended reading lists are published on the Worlds of Words website, organized by grade level bands, K-1, 2-3, 4-5, 6-8, 9-10 and 11-12, with separate fiction and nonfiction lists. The lists are organized around broad themes, including strength through relationships, forced journeys, taking action, locating self in the world, adventures and mysteries and mythological quests. Books that remain in print are kept on the lists each year, while new books from 2024 and 2025 are added.

The books considered for inclusion on the recommended lists are identified by examining the global books sent to the Worlds of Words Center for review purposes, consulting global book award lists and reading book reviews. To be considered, the books must be set in cultures outside the U.S. or involve characters who move between a global community and the U.S. Some of the global books are international books, first published in another country before being translated or adapted for publication or distribution in the U.S. Books are eliminated from the larger set of global literature because of negative reviews or because they are generic and lack a specific global setting or cultural values and traditions. Finally, we carefully examine which books will be of most interest in K-12 classrooms and libraries, based on our backgrounds as educators and interactions with teachers and librarians.

Typically, there are definite trends in the books particularly around themes and countries, but this year the major trend is the range of countries reflected in the books, including Iran, Kenya, Nigeria, Israel, Brazil, Colombia, Lebanon, Morocco, Pakistan and Palestine, along with the European and Asian countries that have dominated global literature for many years. Many of the authors of these books have close connections to the global communities in which their books are set, either living in those communities or writing out of their family heritage or immigration experiences.

In gathering the books, it was immediately clear that there were many more picturebooks than novels with a much smaller number of books to consider for Grades 9-12. Picturebooks are easier to translate and often have more generic settings or focus on animals as main characters, all of which facilitate their use across cultures, but also erases cultural distinctions. The picturebooks on the lists this year include many realistic fiction books, showing everyday life in a specific global community, while fantasy continues to dominate in young adult literature. The fantasy trend is true for young adult literature in general so it's no surprise that this same emphasis held for global literature.

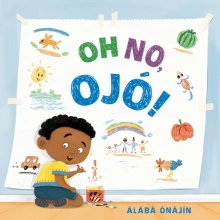

In picturebooks, a continuing positive trend is the portrayal of everyday life in families and communities around the world, such as Oh, No, Ojó by Àlàbá Ònájìn (2025), set in Nigeria, about a young boy who loves to draw so much that he draws in places he shouldn't. Every Wrinkle Tells a Story (David Grossman & Ninamasina, 2024), a translated book from Israel, is a conversation in which a grandfather replies to his grandson's questions about the wrinkles on his face. Another translated book, My Dad is the Best by Eve Pintadera and Joan Turu (2025), is from Spain and focuses on an escalating argument between two boys on whose father is the best and strongest. Honk Honk, Beep Beep, Putter Putt! by Rukhsana Khan and Chaaya Prabhat (2024) goes beyond family to the broader community in Pakistan as a child goes on a noisy rickshaw trip around town.

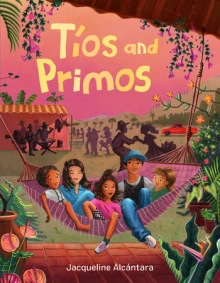

Although books continue to be published that highlight immigration experiences, one interesting set of transnational books focuses on children who are visiting their parents' or grandparents' countries to connect with family and heritage. In Tios and Primos by Jacqueline Alacantara (2025), a girl visiting her father's homeland in Honduras is excited to meet so many new family members but worries about her Spanish, while in Sundays Are for Feast (Leila Boukarim & Ruaida Mannaa, 2025), a young girl visiting family in Lebanon worries she will make a mistake when asked to make hummus for the family Sunday feast. In Hilwa's Gifts (Safa Auleiman & Amail Semirfzhyan, 2025), a boy visits his grandfather in Palestine at the time of the olive harvest, realizing the many ways olives are woven into his family's life. In Nainia's Mountain (Livia Blackburne, 2025), a young girl travels with her grandmother to visit her old home in Taiwan, providing an opportunity to understand her grandmother in new ways. A Second Chance on Earth (Juan Vidal, 2024) is a translated novel in verse from Colombia about a boy who travels to Cartagena to scatter his father's ashes after his sudden death. Uprooted, a graphic novel by Ruth Chan (2024), reverses the typical immigrant journey as a girl feels displaced when her family moves from Toronto to Hong Kong.

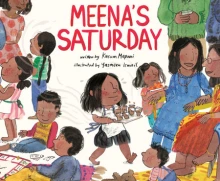

Another interesting set of books is around activism, particularly the depiction of many different forms of activism, from subtle acts of everyday activism to organized protests. Meena's Saturday (Kusum Mepani & Yasmeen Ismail, 2024) is an excellent example of everyday activism as Meena and her Gujarati family prepare for a large family gathering of immigrants from India. Meena notices that while the women and girls do all of the work preparing food, the men are seated at the too small table to eat first. Recognizing the need for change, Meena quietly pulls up a chair next to her father, who puts his arm around her, welcoming her to the table. In a bilingual picturebook, Hokusai's Daughter/Hokusai no Musume (Sunny Seki, 2024), the daughter of the famous Japanese artist, refuses to believe that only men can create great works of art and keeps showing up to share her art. Another example of everyday resistance is evident in picturebooks where children eventually speak up when their names are mispronounced or changed. In Call Me Gebyanesh (Arlene Schenker & Chiara Fedele, 2025), a girl who moves from Ethiopia to Israel gathers the courage to challenge her name being changed to something easier to pronounce. Another type of everyday resistance occurs in Adi of Boutanga (Alain Dzitop & Marc Daniau, 2025) in which Adi is unable to publicly resist her uncle's decision that she must marry at 13. Set in Cameroon and translated from French, Adi's parents find a way for her to escape to a safe place to live and learn.

More organized forms of resistance are depicted in books, such as Save Our Forest by Nora Gasnes (2024), translated from Norwegian, in which a Vietnamese Norwegian girl organizes with friends to lead a protest against a forest being turned into a parking lot at their school. Birds on the Brain (Uma Krishaswami, 2024) involves similar organizing and protests to advocate that the students' city in India participate in a global bird count to document threats to birds.

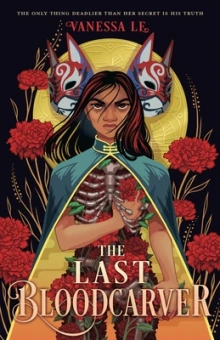

Dark fantasy and horror are having a moment in young adult literature so it's not a surprise that this same trend is happening in global literature as well. Fledgling by S.K. Ali (2024) is a dystopia in an Islamic and Arabic setting that is a fractured world on the brink where the main character must decide whether to trade love for peace. The duology, The Last Bloodcarver (2024) and His Mortal Demise (2025), by Vanessa Le is a Vietnamese-inspired dark fantasy about a teen who struggles with her identity in a high-stakes political drama embedded in a medically based magic system. Finally, A Drop of Venom by Sajini Patel (2024) retells the legend of Medusa as a feminist tale in an Indian mythological world that follows a survivor of sexual assault.

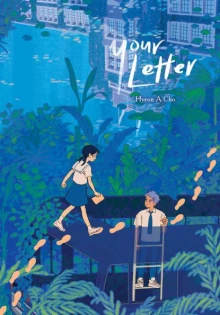

Even though young adult literature is dominated by fantasy and horror, realistic fiction is available, especially in translated books. One of the best examples is Your Letter by Hyeon A. Cho (2024), a graphic novel translated from Korean in which a teen is forced to change schools when she experiences extreme bullying after standing up for another student. On her first day at the new school, she finds an anonymous letter under her desk, giving her helpful information on the school and engaging her in a scavenger hunt that brings back hope into her life. This book is an excellent example of a novel within a specific cultural setting that raises issues that cross global contexts.

We invite you to spend time with the updated K-12 recommended global book lists to locate books that connect to your interests and needs. Each book includes a short annotation to describe the plot and indicates the country or culture within which the book is set. In addition, all of these books are published in the U.S. and so should be available through various sources. If you visit Tucson, come to Worlds of Words Center to browse through the actual books. Read the world!

WOW Currents is a space to talk about forward-thinking trends in global children’s and adolescent literature and how we use that literature with students. "Currents" is a play on words for trends and timeliness and the way we talk about social media. We encourage you to participate by leaving comments and sharing this post with your peers. To view our complete offerings of WOW Currents, please visit its archival stream.