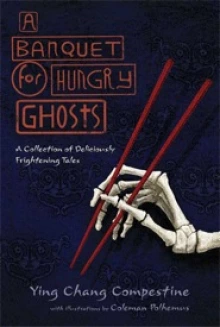

A Banquet for Hungry Ghosts

Written by Ying Chang Compestine

Illustrated by Coleman Polhemus

Holt, 2009, 180 pp.

ISBN: 9780805082081

According to Chinese tradition, those who die hungry or are treated unjustly return as ghosts to haunt the living. Some are appeased by food and so families take a traditional Chinese banquet to the graveyard twice a year—but not all ghosts are successfully placated. Compestine serves up an eight course banquet of appetizers, main courses, and desserts in the form of ghost stories set in different time periods and parts of China. From the building of the Great Wall to the modern day, hungry ghosts torment those who have wronged them. The book is arranged in eight chilling stories, each named after the dish that is incorporated into the story. Following each ghost story is a recipe and a note that describes the historical, cultural, and political context of the issue at the center of that story. The unique structure of the book and the multi-genre nature of the stories, recipes, and informational notes provide for an engaging—and unsettling—read. The occasional black-and-white illustrations create a spooky air through the contrast of beautiful and gruesome images depicting the ghosts and their victims.

Compestine (2010) states that she was asked to write a sequel to her award-winning book, Revolution is Not a Dinner Party (2007), but was not interested in writing more about the Cultural Revolution. She was struck by the inequality and corruption in modern China during one of her many trips back to visit family and decided that she wanted to write about these social problems. Her experiences as a child during the Cultural Revolution had taught her not to express her opinions openly. Instead of criticizing Chinese society and the government directly, she decided to use food as a metaphor to target modern social problems and ghosts as a weapon for justice to exact revenge and right wrongs. The disparity between rich and poor, the corruption of monks in Buddhist temples, the mistreatment of mental patients, organ harvesting from prisoners, bribery by officials and doctors, the killing of endangered species, and a rigged legal system all fed Compestine’s imagination and storytelling. People get chopped up, buried alive, and grabbed by skeletons reaching up from their graves in these chilling and gory ghost stories that serve up both entertainment and subtle social commentary. Compestine even finds a way to comment on the harsh university exams that she remembers well from her own childhood and their use to determine who will have an opportunity for a good life or a life of hard labor.

Compestine grew up in Wuhan, central China, during the time of the Cultural Revolution and became interested in writing as a child with the encouragement of a teacher. Her father was a surgeon and she spent a great deal of time in a hospital compound, an experience that is integrated into this book. She left China to attend the University of Colorado as a graduate student and now lives in northern California with her husband and son. She states that she began writing as a way to stay close to the country she loves. Although she has now lived in the U.S. for over 20 years, she frequently returns to China to visit her family and to tour in different regions of the country in her quest to understand the diversity of her own culture in greater depth. Many of these different areas of China have been used as the settings within the ghost stories. Compestine has also written cookbooks, hosted her own television cooking show, and worked as a food editor for magazines, and so draws from this knowledge base to provide the food metaphors within the stories. Her web site, http://www.yingc.com, provides articles and interviews in which she talks about her life and the experiences behind her books. Compestine begins this book with an Author’s Note that introduces her motivation for writing this book and the role of ghosts and food within Chinese culture. The placement of this note at the beginning of the book establishes a strong cultural context for the stories and makes a more effective framing for the book than when these notes are hidden at the end of a book and overlooked by most readers. The integration of a short historical note after each ghost story gradually builds a deeper understanding of Chinese culture than if these notes were included in an afterward as is typical in children’s books.

This book could be paired with Compestine’s other books in which she explores Chinese culture, particularly Revolution is Not a Dinner Party (Holt, 2007), Boy Dumplings (Holiday House, 2009), and The Runaway Rice Cake (Simon & Schuster, 2001), along with her cookbooks, especially Secrets from a Healthy Asian Kitchen (Penguin, 2002). Another interesting pairing is other ghost stories that provide a social commentary, in particular The Dark-Thirty: Southern Tales of the Supernatural (Patricia McKissack, 1992), which are rooted in African American history and preceded by a short introduction explaining the historical incident or custom in which each story is based, as well as From Another World (Ana Maria Machado, 2005), a Brazilian ghost story about slavery and mass murder. Finally, readers could explore other books that connect stories with recipes and culture, such as Salsa Stories (Lulu Delacre, 2000), Everything on a Waffle (Polly Horvath, 2001), La fiesta de las tortillas/The Festival of the Tortillas (Jorge Argueta, 2006), and Saturday Sancocho (Leyla Torres, 1995).

Compestine, Ying Chang (2010). Presentation at the University of Arizona, March 11, 2010.

Kathy G. Short, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona

WOW Review, Volume II, Issue 3 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/review/reviewii3.