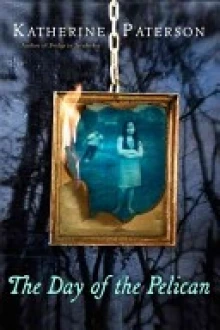

The Day of the Pelican

Written by Katherine Paterson

Clarion, 2009, 160 pp.

ISBN: 9780547181882

This book focuses on the political and religious conflicts and struggles in the Eastern European regions of Serbia, Bosnia and Kosovo at the brink of the 21st century. It also includes the immigrant experiences of Muslims. The story revolves around a coming-of-age theme through portraying the struggles for survival of a young girl, Meli Lleshi, an eleven-year-old, who has to grow up fast due to unrest in her country of Kosovo. She is ethnically an Albanian Muslim who is living in Kosovo.

Meli is portrayed as a quiet thoughtful child who does what is required of her in taking care of her three younger siblings and doing her housework and schoolwork. Her father is presented as a person who wants to live peacefully, rather than wasting time in hating fellow human beings, including Serbs. The story unfolds through the thoughts of the protagonist, who struggles to make sense of her life as she goes through the tumultuous events triggered when she is caught drawing a caricature of her teacher in school. The family of seven, consisting of parents and five siblings, are a Muslim family from rural upbringing. They are targeted by Kosovars and Serbians alike because of their humble background and their alliance to the freedom fighters struggling for the rights of the Albanian Kosovars against Serbian oppressors known as the KLA (Kosovo Liberation Army). The major role in this story seems to be shared by Meli and her brother, thirteen-year-old Mehmet.

Their peaceful, albeit oppressed, existence is shattered when Mehmet is taken away (as are other Muslims) by the Serb police and is tortured and left to die. The KLA saves him and he comes back home full of hatred for Serbs, who are no longer an abstract enemy but a real one because of his experience. The family is forced to flee their home and take refuge in the mountains; camping with other Kosovars trying to escape the tyranny of Serbians. There they have the KLA keeping an eye on their welfare, but their position is given away and they are forced to move to their family home on the farm, along with their extensive extended family. A group of Serbs burn their home and take away everything of value, forcing them to cross the border into Macedonia, where they live within the confines of a refugee camp. Their father finds what he sees as the only way out of their present condition, due to his concern about his son’s constant admiration and connection to the KLA, by applying for asylum in the U.S. After they move to the U.S. they are grateful to the Christian groups that sponsor them and appreciate their own hybrid existence as free citizens. In the willingness to assimilate they try to learn English and celebrate Christmas. The mother is shown as influencing the family’s decisions and as busy taking care of the home and the younger children. The events of September 11th 2001 put the family again in the position of being labeled and profiled.

Family and family unity are of the utmost importance in this book as are the themes of kindness and forgiveness of oppressors even when the family goes through so much negativity in relation to ethnic prejudice and cleansing within Kosovo as well as in their new adopted country. This is one of the few refugee books that show the negative as well as positive aspects of their immigrant experiences in the U.S. The U.S. is not portrayed as a golden land of opportunity without critique, as found in most books.

The dialogue and bantering exchanges between the characters emphasize the struggles of this ethnic group and their hatred of Christians and Serbs. On the second page of the novel, Meli’s questioning and discerning thoughts are articulated by the words, “Why do Serbs hate us so?” and she counters with, “though to be honest, most Albanians hated Serbs just as fiercely…she could never understand hate like that” (p. 2). The family members experience hate firsthand in this book. Meli recognizes that all people involved have to take responsibility for their feelings and interpretations of other groups in order to work towards peace. Hate and mistrust are part of life and something we each have to recognize as being within us and to take responsibility for instead of just blaming others. The story is not dated but very much portrays the present through the existence of amenities, such as television, cars, and airplanes.

The Albanians in Kosovo are portrayed as if living only for the immediate present. As long as their family is all right and their day passes without any negative incident, all is well in their lives, a common characteristic of people in crisis and at great danger. They do not question or try to find out the reason behind anything, even a range of Alps being named; “the Cursed Mountains” (p. 2). They are presented as people who mind their own business. When Christians sponsor them in the U.S., they are confused by the contrast in Christian behavior. The father allays their fears by saying that, “at one time all of us were Christians…until the Turks came, we Albanians were Christians” (p. 95). His comments show the difference in world-views; not to judge one or the other but to make readers aware of the difference in those views.

One concern is that the story comes through more as a representation of the many faces of Christians than as representative of diversity in Muslims living in Eastern European countries who underwent ethnic and religious cleansing because of their religious beliefs. Christians as oppressors and then as saviors again seems to cancel out the discourse that represents them as a negative religious group, through the events within those regions. The story underplays Islam as a religion and the Muslim experiences by choosing to represent a family who are non-practicing and thus disconnected from their religion. Meli after 9/11 repeats twice as if in her defense, “I am not a religious person…but if I have to choose Christian or Muslim, then okay, I am Muslim” (p.127). The story makes light of Muslims eating pork by portraying it as acceptable. “The welcomers came with gifts: warm socks, gloves…and a ham for their Christmas dinner…they hadn’t eaten pork in Kosovo--it was against Muslim custom-but somehow in this land of strangeness it felt fitting” (p. 114). It is forbidden to eat pork in Islam. The behavior of this Christian group seems dubious as to their intention, although the presentation of the incident can be viewed as a critique of Americans who don’t bother to educate themselves and understand a world-view beyond their own.

I had a strong connection to this story as it dealt with the forced fleeing of a family. My own experiences with just such an incident when I was a young girl in the Eastern part of Pakistan in 1971 (presently Bangladesh), made it come alive through this story. I further appreciated some of the significant points brought forth in this story; for example, issues of immigration for religious groups; the role of the U.S. in stopping, albeit late, the ethnic and religious genocide in the regions; the helplessness of the Kosovars to defend themselves due to a lack of unity, training, and funds; the oppression of the Muslims by the Serbs; and ethnic prejudice and labeling of Muslims by Americans in the aftermath of 9/11.

Katherine Patterson was inspired to write this story through her contact with the Haxhiu family, who came to the U.S. through the sponsorship of a church in Vermont as well as Mark Orfila who lived in Kosovo during the troubling period of their history. She herself has not visited Kosovo. The book also contains extensive historical notes. She provides an almost dispassionate and calm account of the horrendous events which may have been due to her deep research on the subject so much so that the spontaneous storytelling that she excels in is minimized. She does not address the extent of the actual brutality that occurred by portraying that the family was allowed to leave without being beaten, raped, and/or mutilated by Serbs.

The story touches on aspects of Albanian/Kosovar culture that might be true in some instances but cannot be taken as representative of the whole of the society. Variations of some of the same thematic threads can be found in another novel: The Story of My Life: An Afghan Girl on the Other Side of the Sky (2005) by Farah Ahmedi. Ask Me No Questions (2007) by Marina Budhos portrays Muslim experiences in the U.S. after 9/11. Other novels that focus on and portray the religion of Islam as an integral part of the characters living in the Western countries are: From Somalia with Love (2009) by Na’ima B. Robert set in England, Ten Things I Hate about Me, (2009) and Does My Head Look Big in This? (2008) by Randa Abdul Fatah, both set in Australia.

Seemi Aziz, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, Oklahoma

WOW Review, Volume II, Issue 3 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/review/reviewii3.