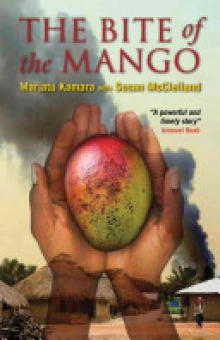

The Bite of the Mango

Written by Mariatu Karnara and Susan McClelland

Annick Press, 2008, 216 pp.

ISBN: 978-1554511587

Mariatu Kamara begins her memoir by recounting everyday village life in Sierra Leone. It is an arduous agrarian existence; food is scarce and families are too poor to school their children. Female circumcision and polygamy are traditional, as is communal living where everyone helps each other. But Mariatu’s life changes irrevocably when a brutal civil war rips through the country. Armed rebels, many no older than twelve-year-old Mariatu, rape, maim, or murder villagers. After forcing her to witness these atrocities, the rebels chop off her hands, jeering that she will not be able to vote for “the President.” Mariatu does not even know what a president is or does. Mariatu takes the reader on a haunting journey through the war-torn bush to a rudimentary hospital and then on to a refugee camp in Freetown. While at the refugee camp, she encounters other youth, who in the face of dire adversity, cling to hope, courage and life itself. Together they beg, share food and even start up a drama company as a means to speak out about the horrors of war and the need for reconciliation. Interviewed by journalists, Mariatu’s story spreads and eventually leads to asylum and formal education in Canada. Her powerfully understated narrative is alive with courage, hope and advocacy for social change. “I may not have hands, but I have a voice,” declares Mariatu.

The book’s title and cover illustration depicting hands offering a mango, echo a pivotal scene from the story where a man, caught in the crossfire, takes pity on the near-dying Mariatu. He gives her a mango, directs her to the hospital and encourages her to look forward rather than back, saying, “It’s the only place to go, my sweet child.” Mariatu’s real-life disorientation is mirrored at times by tangible gaps in the narrative, particularly concerning her sexual assault and bewildering relocation in Canada. These gaps in the memoir also suggest that co-writer Susan McClelland has carefully avoided the major pitfalls of ghost writing— those of intrusion into and interpretation of another person’s story. This book is testament to the truth that we live at a time when we depend upon each other to uphold each other’s stories, especially during times of conflict. Major themes in this book are war and its impact on children and women, community dislocation, disability and resilience, and friendship and advocacy.

End notes include historical and contemporary information about Sierra Leone and the civil war that raged from 1991- 2002 as well as information about both authors. Susan McClelland is a journalist who writes predominantly about children’s and women’s issues, and was the recipient of the 2005 Amnesty International Media Award. Mariatu Kamara has worked with several NGOs (non governmental organizations) and became UNICEF Canada’s Special Representative for Children in Armed Conflict. She established the Mariatu Foundation (http://www.mariatufoundation.com), which seeks to provide shelter and healing to women and children in Sierra Leone. Kamara has also been the recipient of several awards including the 2009 Voices of Courage Award in honor of her advocacy work. She is currently studying to be a counselor at George Brown College in Toronto. For further information about her work with UNICEF visit http://www.unicef.org. A lesson plan written by both authors to aid discussion about the book and civil war is available at www.annickpress.com.

This disturbing memoir, devoid of self-pity, is suitable for older adolescent readers, aged 14 and over. Its brilliance lies in simultaneously revealing the shocking brutality of war and the immense will and courage of youth to rise up for justice. To extend thinking about the civil war in Sierra Leone and for a male perspective on the complex causes that compel children to take up as well as put down arms, a natural companion to this book is A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier (Ishmael Beah, 2007). Beah’s graphic descriptions highlight how hunger, fear and ignorance work in unison to undermine the humanity in many other regions in Sierra Leone. Memoirs by Kamara and Beah could also be paired with Secrets in the Fire (Henning Mankell, 2003), which retells the story of the spirited Sofia in Mozambique as she tries to build a new future for herself in the aftermath of genocide, and in a landscape littered with landmines. Parallel experiences of war and the power of young people to resist hatred to become seeds for peace can also be found in: Thurma’s Diary: My life in Wartime Iraq (Thura Al- Windawi, 2004), Out of War: True Stories from the Front Lines of the Children’s Movement for Peace in Columbia (Sara Cameron, 2001), and Bamboo People (Mitali Perkins, 2010).

Chloë Hughes, Western Oregon University, Monmouth, OR

WOW Review, Volume III, Issue 4 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/review/reviewiii4.