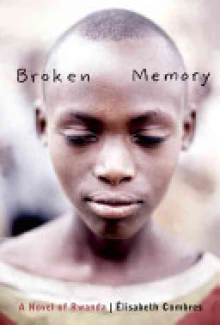

Broken Memory: A Novel of Rwanda

Written by Élisabeth Combres

Translated by Shelley Tanaka

Groundwood Books, 2009, 139 pp.

ISBN: 978-0888998927

Slide behind there, close your eyes, put your hands over your ears. Do not make the slightest move, not the slightest noise. Tell yourself that you are not in this room, that you see nothing, hear nothing, and that everything will soon be over. You must not die. (p.17)

This historical fiction novel focuses on the life of a young survivor of the Rwanda genocide in 1994. Emma was five years old when she lost her mom at home, a supposedly safe and happy place. Emma barely survives by hiding herself behind the door. Even though Emma doesn’t "see" the event, but the rest of her senses vividly witness her mother being murdered. Even though her mom says "everything will soon be over", ironically her nightmare just begins and haunts Emma until her memory of her home and mother grows weak and even broken. Luckily an old Hutu peasant woman, Mukecru, takes Emma in, risking her own life to hide her. Nine years later, those who were responsible for the massacre in Emma's village are brought to trial. Emma unavoidably faces them in town. The journey to recovery for Emma starts when she must recall what happened. She has to look back in order to look ahead.

Emma’s ways of taking action are personal but necessary for social change. Often taking action for social change is assumed to be some kind of resistance to fight against injustice. This isn’t the case for genocide survivors like Emma. Emma’s actions start from the small but universal requirement--courage. How can a young child change society when masses of people have already been killed because of who they are? How can a young child take action for a social change when that child is the only surviving member of her family, yet her life can be extinguished at any time? Broken Memory seeks the meaning of taking action in such devastating conditions. Hope is a luxury for the surviving children of the Rwanda genocide. The meaning of taking action for Emma is to have courage to face the internal pain and trauma in her memory.

It takes a long time until Emma is ready for taking her first critical step toward social change. Emma’s story begins with the voice of a young five-year-old child and ends with that of a 24-year-old woman. She suffered so much that her focus is on her own security, but her gradual yet incomplete recovery affords room for others. The small but powerful form of taking an action is reaching out to another young Tutsi victim, Ndoli, who is accused of the deaths of his relatives. They grow together as friends and companions.

Broken Memory shows what it takes to overcome trauma yet not remain defeated by it. Also, the book emphasizes the survivors’ hope for social change in the epilogue. For instance, Emma couldn’t read well when she was younger and she becomes a teacher who is “now at peace with her past and looks to the future with confidence” (p.131). The old man who helped Emma works for children who have become orphans because of AIDS.

Emma’s story reflects the voices from massive massacres, but at a deeper level it shows the tragedy of human classification. The author’s note provides historical contexts of Rwanda and is informative to a young audience. Rwanda genocides were the consequence of the Hutu government’s anti-Tutsi discrimination practices, which eventually led to the genocide of the Tutsis by Hutu in 1994. It is sad to learn that the trigger of such tragedy originated from the colonizers’ policy of human classification.

The author, Combres, is a former journalist and current reporter in France, Latin America, and Africa. She conducted research around the Rwanda genocide from a wide range of sources—interviewing genocide survivors, psychologists, and humanitarian aid workers who work with child survivors suffering from trauma. That may explain how the portrayed tensions and fear against other human relationships differentiates this book from typical depictions of war victims as an innocent group. A collection of different stories from genocide survivors is reflected throughout the story. The narrative style—telling such a sad story in a matter-of-fact manner—provides strong realism.

Broken Memory was originally published in France, and then Shelley Tanaka translated it into English. Tanaka has a long history of working in the publishing business and has edited numerous books for authors, such as Deborah Ellis. She is also a writer and illustrator. Several of Tanaka’s nationally recognized, award-winning books are nonfiction books.

This novel can be read alongside Speak (Laurie Halse Anderson, 2001), The Killers Tears (Anne-Laure Bondoux, 2003) and Our Stories and Our Songs: African Children’s Talk about AIDS (Deborah Ellis, 2005). Protagonists in Speak and The Killers Tears both experience traumatic events and their journeys to face their pain are the door of overcoming their difficulties through relationships. In Our Stories and Our Songs, every day is painful and traumatic for children who lose their family members to AIDS and will soon be victims of AIDS themselves. However, their courage and hope for social changes resemble other characters in Speak, The Killer Tears and Broken Memory. These books may open a powerful discussion about the meaning of taking action and questioning what you can do when there seems to be no hope.

Yoo Kyung Sung, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM

WOW Review, Volume III, Issue 4 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/review/reviewiii4.