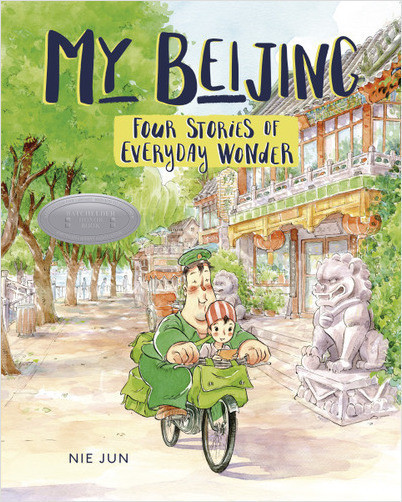

My Beijing: Four Stories of Everyday Wonder

Written and illustrated by Nie Jun

Translated from French by Edward Gauvin

Graphic Universe, 2018, 128 pp

ISBN: 978-1-5415-2642-6

My Beijing is a watercolor graphic novel created by cartoonist Nie Jun. It depicts four scenes of everyday fantasies happening in Hutong, a traditional-style narrow alley commonly seen in residential areas in Beijing. The first story, “Dream” introduces the protagonist Yu’er (“little fish” in Chinese) and her grandfather. Dreaming of becoming a professional swimmer, Yu’er is rejected by the local training center because of her disability. Her grandfather creates a self-training program at home to help “little fish” realize her swimming dream. The second story, “Bug Paradise,” illustrates the grandfather’s dream when he, as a boy, protects Yu’er from bullying and shows her the beauty of insects in nature. With an element of magical realism, the dream is depicted as Yu’er’s real-life adventure. The third part tells a story of “how I met your grandmother” through the time travel of a letter. Grandfather helps Yu’er deliver a letter to commemorate her grandmother, and the letter indeed finds the right recipient. The last story is about a “kid at heart.” Grandpa Pumpkin never had an opportunity to paint in his early years, and so, after retirement, he spends all his time painting to make up for his unfinished dream.

This English version is translated from the French title “Les contes de la ruelle” (literally meaning “The Tale of the Alley”), which is translated by Qingyuan Zhao and Nicolas Grivel from the Chinese version “The Fairy Tale in Hutong.” The “everyday wonder” in the English subtitle touches on the magical power of dreams shared in all the tales. The light warm watercolors in the graphic novel panels add a sense of nostalgia, corresponding to the stories’ transcendence of past, present, and future.

The author and illustrator, Nie Jun is a cartoonist in China. He developed early interests from Lianhuanhua, a type of comic strip popular in China in 1970s and 1980s. After graduating from the China Academy of Art, Jun started working on comics and picturebooks, while teaching fine arts to college students. His drawing style is also influenced by Japanese and French comic creators. Many of his works focus on wonder, dream and children. During his creation of art, Jun says, “I’ve always wanted to draw cartoons with Chinese characteristics, work that represents China. I want my cartoons to look Chinese, not Western or Japanese or South Korean. If people look at my cartoons and say ‘they’re very Chinese’, then I’ll feel like I’ve done a good job” (CCTV, 2005).

A Hutong is the name for the narrow streets and alleys in Beijing that are formed by traditional courtyard homes (siheyuen). It also refers to the neighborhoods connected by it, which nowadays have been protected as historical heritage sites. In the author’s note at the end of the Chinese version, Jun mentioned the nostalgic nature of this book: “As we grow up, the simple happiness we used to have has become rare. Those old-day friends have drifted away. Those little buddies who used to catch bugs in the fields and cut stamps off envelopes for collection have lost contact. No one has the patience to send a hand-written letter anymore. Our life pace is faster, yet we are further away from each other.” During his field research throughout the Hutong, Jun discovered the good old days when neighbors would gather in the summertime under the shade of trees, telling stories of life and the outside world. Despite the rapid changes in life, people in Hutong “are still here, living as they used to, living as who they are, like characters in fairy tales.”

On Douban Book, one of the most popular websites of book recommendations and reviews for Chinese readers, people mention the authenticity of Beijing Hutong depicted in this book. For example, the White Stupa Temple and the Yinding stone bridge in the book are real landmarks in Xicheng District, where many Hutong residences are spread out. The tricycle with a cart at the front is a commonly used form of transportation. Other details like the poles with electric lines, the green postbox and the all-green outer wear of the postman, the main door to a courtyard, and the tiled roofs are all accurate details that remind readers of their childhood, filled with “an old Beijing flavor,” which is used to describe something authentic to local Beijing style (Douban, 2016).

As someone who spent most of her life in northern China, the back cover of the Chinese version is déjà vu to me. The view of the street corner without people contains rich details from my childhood: the big green bicycle means there would be a postal worker around; many convenience shops have a bird cage hanging from the roof outside; in front of the shop window, there would be a cooling cart selling yogurt in white ceramic bottles, and most cooling carts or fridges would have a polar bear logo sponsored by the Arctic Ocean soda drink; on the blackboard facing customers, there would be brands of tobaccos with their prices written on it; the white-red electric tricycle was for the milk delivery! The back cover of the English version uses a picture of the bridge, and it works as a background for the short introduction to the book and the author. Another interesting difference is that, at the end of the Chinese version, the “Hutong sketchbook” includes eleven sketches of daily scenes, some with human figures and some without; while the English version includes a short introduction of Hutong with a photo and only keeps five sketches with human figures. These different choices for the back cover and sketchbook pictures might indicate the publishers’ adaptation for the audience.

My Beijing can be paired with the Newbery honor book El Deafo, a graphic novel written and illustrated by Cece Bell (2014). The author depicts the main character as a bunny who is deaf. The choice of the character shows an ironic contrast of having conspicuous ears that cannot hear, which is similar to Yu’er, a little “fish” that cannot swim. Instead of treating disability as a disadvantage or problem to be taken care of, these two stories portray people who have a disability as just one part of who they are, equal to others. In Jun’s words, he wants “to show a peaceful way of getting along in the story. People don’t show a deliberate pity or give preferential treatment to Yu’er. They don’t regard her differently from others” (Kinross, 2018). My Beijing is an engaging read to readers of all ages, with characters and themes that transcend languages and cultures.

Both the French and Chinese versions of My Beijing were published in 2016, with the English translation being made from the French version. Before this work, Jun has published most of his major works in France and received good reviews. In his response to the publisher, Jun mentioned that he incorporated his childhood memories into the book. He also clarified why Yu’er does not use a wheelchair: “a wheelchair is very inconvenient in the old Beijing streets. The gates have high thresholds. There are also many stone steps and no elevators. That’s why Yu’er usually uses a crutch. And the cart she is pushed in is not like the cart we see in supermarkets. In Beijing, we call it ‘Dao Qi Lv’ (riding a donkey in reverse). It’s a common bike with a cart in front of it, and it’s very convenient. This design is more like the rest of what you see in the old streets, and it makes Yu’er’s life not that different from others” (Kinross, 2018).

References

CCTV. (2005, October 17). Cartoonist: Nie Jun. China.org.cn: http://www.china.org.cn/english/NM-e/145548.htm

Douban. (2016, October 1). 老街的童话. Douban: https://book.douban.com/subject/26883964/

Kinross, L. (2018, November 7). ‘Learn from each other’s heart’ is cartoonist’s message. BLOOM: http://bloom-parentingkidswithdisabilities.blogspot.com/2018/11/learn-from-each-others-heart-is-chinese.html/

Xiajie Wang, University of Arizona

© 2021 by Xiajie Wang

WOW Review, Volume XIV, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on work by Xiajie Wang at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/review/xiv-1/10/

Thanks you! What an eye opening review!!!! So well written and dedicated to the truth of representing our daily lives, our first thoughts, our judgements. At 70 I reflect back on my life and realized at a younger age that I unknowingly judged sight, smell, touch, hearing and taste from my surroundings and events! It is so rewarding that at an early age our senses can be richly directed from reading these kind of observed stories. Opening our eyes and hearts to knew horizons!