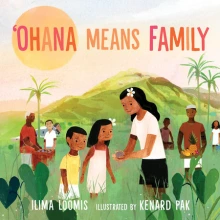

'Ohana Means Family

Written by Ilima Loomis

Illustrated by Kenard Pak

Holiday House, 2020, 32 pp

ISBN: 978-0823451180

Written in the cumulative style of The House that Jack Built, award-winning author Ilima Loomis and illustrator Kenard Pak skillfully demonstrate Hawaiian cultural practices that connect humans to the environment through preparations for a lū'au (Hawaiian feast). The book opens with a picture of poi (a staple food of the Hawaiian people, pounded into a smooth paste from the taro plant) in an 'umeke (wooden calabash) and states, "This is the poi for our 'ohana's lū'au.” This illustration and statement, although seemingly understated, says much. Poi is made from kalo (also known as taro), 'ohana means family or relative and suggests the importance of this food for the family, and at lū’au people commonly come together to eat in Hawai’i.. According to Hawaiian cultural practitioner, Roxane Stewart, "the poi (in how the author later traces the pathway from land to bowl) feeds the 'ohana nutritionally but also feeds the 'ohana spiritually, emotionally, physically, etc. in the practices that lend to that poi-filled 'umeke (wooden calabash)” (personal communication, March 15, 2022). This illustration and text introduces the significance of this particular food in the Hawaiian culture and how it connects ʻohana with the natural world, and each other. It is an honor to feast and celebrate these relationships and connections. At the end of the book, a note on kalo and poi from Noho'ana Farm on Maui by Hōkūao Pellegrino supports the cultural authenticity of the cultural and farming practices. In the author's note, she explains her purpose and intention focused on the idea that "food connects us."

The story starts with poi, but as the narrative builds, it shows how everything in nature is interconnected and plays an important role in the outcome of the harvest--from the mud where the taro grows to the clear and cold water, which needs to cover the mud so the kalo can flourish. In the text, the sun "warms the wind" that "lifts the rain," that "feeds the stream," that "floods the land." Each action builds on the next, carefully emphasizing the interdependence that each element has with one another and the cyclical patterns in nature. It underscores the scientific knowledge needed to sustain growth and weaves in cultural beliefs and practices related to growth, preparation and consumption of kalo. Hawaiian cultural practitioner, Stewart further comments, "this interconnectivity is at the core of how Hawaiians see & understand their environment & their role in it - holistically (vs linearly)."

'Ohana Means Family is the title of the story and is also part of a popular quote from the 2002 Disney movie, Lilo and Stitch; however, a number of other implicit cultural nuances can be found in the text and illustrations. For example, the cultural significance of passing on generational knowledge is depicted through the text, "work the hands so wise and old" along with the illustration which shows an elderly person harvesting kalo in the field, giving it to a child, while another watches. There is reference to "lands that's never been sold," which presumably refers to Hawaiian perspectives on being caretakers rather than owners of the land. Stewart points out the meaning of 'āina (often translated as land) is more than land, "being that which feeds," drawing the nutritional cycle between land, poi an, ‘umeke.

The deep relationship and reciprocal exchange between human and nature is beautifully depicted through the poetic text and illustrations. For example, the cover and most of the pictures in the story show people either interacting with each other (giving and receiving something) or working the land. Methods for learning and teaching are emphasized in some pictures where youth are shown learning by closely observing the young adults and the older generation working. On other pages, the children are "learning by doing" and participate in the work alongside the adults. The aerial view of the kalo fields shows that many hands work together to feed the family, which highlights the collective aspect of the Hawaiian worldview. Finally, an emphasis on gratitude for nature is suggested with the line, "This is the 'ohana, the loved ones we hold, who give thanks" for the sun, wind, rain, stream, land, and water.

This text can be paired with picturebooks Naupaka by Nona Beamer and Caren Ke'ala Lobel-Fried (2008) or The Fish and Their Gifts by Joshua Kaipohohea Stender (2004), which show the Hawaiian worldview perspective on the reciprocal relationship between human and nature.

The author Ilima Loomis was born and raised in Hawai'i and specializes in writing about healthcare, science and Hawai'i. She has published several other children's books: Eclipse Chaser: Science in the Moon's Shadow (2019), and Ka'imi's First Round Up (2008). More about her and her work can be found on her website.

Illustrator Kenard Pak has illustrated picturebooks such as Have You Heard the Nesting Bird (2014) and authored and illustrated a series of books on seasons: Goodbye Summer, Hello Autumn (2016), Goodbye Autumn, Hello Winter (2017), and Goodbye Winter, Hello Spring (2020). His official website is: https://www.pandagun.com/.

Michele Ebersole, University of Hawaii-Hilo

© 2022 by Michele Ebersole

WOW Review, Volume XV, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on work by Michele Ebersole at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/review/xv-1/7.

WOW review: reading across cultures

ISSN 2577-0527