Bringing Global Themes into a “Local” Classroom Discussion

By Amy Gaddes

By the end of May, I was wrapping up a year of instruction with a group of fifth graders in my K-6 elementary setting in a suburban school district just outside of New York City. As a fifth-grade English as a Second Language (ESL) teacher and literacy specialist, I spent the year with a unique group of six English Language Learners (ELLs) and seven native English speaking, or mainstream students, who had been identified as ‘struggling readers’ by their scores on standardized and local assessments. Because of the unusual configuration of the class, I was careful to create community-building opportunities for these literacy learners who came from very diverse linguistic, cultural, and academic backgrounds. Prior to this year’s assignment, these same six ELL students came to my class in a pull-out model of instruction. Now, they were placed with their native English-speaking peers for ELA instruction beyond that sheltered environment.

As an ESL teacher, I believe that in addition to meeting district and state standard-driven mandates, my primary goal is to help maintain and nurture the academic and language learning confidence of my English Language Learners. Over the school year, we worked hard as a group to foster an understanding of our unique backgrounds. The class was very cohesive and supportive of each other as learners. Friendships were fostered that the ELLs may not have had the opportunity to develop when isolated from their peers in a pull-out program. We were unified as a learning community, but I still felt the need to help the mainstream students develop a deeper understanding of the immigrant experience of their peers and their families.

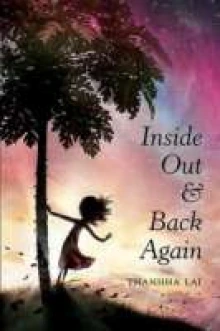

I selected Inside Out & Back Again, by Thanhha Lai (2011) as a text that might create that understanding. This sensitive text holds many opportunities to frame the deeper discussions I longed to have with my students. The group demonstrated a developmental and emotional readiness to go deeper into our shared experiences. The text’s linguistic nuances and geographic and historic aspects may have been lost to the students without my support, so I chose to read this poetic novel aloud. The story is narrated by Hà, a young Vietnamese girl who, with her family, immigrates to the United States during the height of the Vietnam conflict. Hà painfully articulates her language and cultural loss and the arduous task of learning English with its ‘hissing sounds’ and ‘confusing grammar rules.’ This protagonist became a spokeswoman, a voice, to help my young English Language Learners begin a dialogue with their peers about their own losses and challenging gains. At the same time, the native speakers identified similar experiences within their own families.

I invited the students to engage in written conversations by ‘talking’ to the protagonist about her experiences. One student, who emigrated from Mexico at a young age, told the protagonist in a script that he too felt like everyone was staring at him when he was arriving at the airport. This memory, from several years back, was unearthed and explored through the student’s meaningful connection.

After dialoguing with the protagonist, the students were ready to talk to each other. I created question cards with starting ideas to help frame the dialogue between partners, one English Language Learner and one mainstreamed learner. These cards supported the conversation about the specific immigration stories the ELLs carried. Questions offered to the mainstream students to begin a dialogue with their ELL peer included:

- What did your family tell you about learning English?

- Tell me about your house in your country compared to your first house here in America.

- What were your first English words?

- What did you think about American food?

- How does it feel to know 2 languages?

Questions that the ELLs could start asking their mainstream partner included:

- What is it like when a new ELL student comes to your class?

- Why does Hà talk about loneliness in her poem, "Out the Too-High Window?"

- Why do you think Hà's mother told her children that they must master English?

- Why do you think the sponsor’s wife insisted the Vietnamese children keep out of her neighbor's sight?

- Why do you think Hà has to practice 'hissing like a snake' in order to speak English?

The children were invited to choose a card. By offering these questions, I tried to support students’ comfort levels in dialoguing about the character's experience as well as help them establish their own perspectives based on their own experiences.

A student from Pakistan described having to leave her new bike and all her toys when she came to the United States. A boy from the Philippines poignantly wrote about parting from his mother and baby brother. One mainstream student sadly shared his experience moving from Georgia and missing a family funeral. As the students shared what was left behind in their young lives, they connected personally to each other as well as to the text’s protagonist.

Lai’s Inside Out & Back Again provided a tool to talk about the diversity of perspectives and experiences in the world around us. By creating opportunities for the students to explore their experiences through written dialogue, a space was created that validated each child.

References

Lai, T. (2011). Inside out & back again. New York: HarperCollins.

Amy Gaddes is an ESL teacher at the Gotham Avenue School in Elmont, New York.

WOW Stories, Volume IV, Issue 3 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/iv3.