We Speak for the Trees!

Fourth Graders Investigate their Global Relationship with Nature

By Liza M. Carfora

Often when we consider addressing global relationships with our students we select texts that address or introduce cultures from around the world; we focus on the perspectives and lifestyles of people different from our own. Seldom do we consider our global relationship with nature.

Working with a group of twelve fourth-grade English Language Learners in a Saturday morning literacy program gave me the space to consider global relationships with nature with children using children’s literature. In early October, just as the trees were beginning to change colors for the fall season, my co-teacher and I invited our students to take a nature walk. We gave the children sketchbooks and asked them to sketch their observations of nature. Wanting them to have authority over their inquiry, we hoped this walk would elicit possible topics of interest to study over the course of the program. Excited to get outside and out of the classroom, they touched snails, ran under trees, and touched the leaves still damp from the morning air. When we returned to the classroom, we listed all the things we noticed on our walk and charted possible topics for our study. It soon became clear that the majority of the students were curious about trees.

To facilitate our initial conversations we read Fernando’s Gift (Keister, 1995), a bilingual text about a boy living in the rainforest of Costa Rica, and Our Tree Named Steve (Zweibel, 2005), a text about a family’s relationship with the large tree that grew outside their home. In selecting these texts, particularly Fernando’s Gift, we hoped the children would reflect not only on their relationship with nature in New York, but also with how they remember nature in their homeland. Responding to the question, “What is close to your heart in nature?” one child, who emigrated from Honduras, remembered how much he loved the red and white bird that would sit in the tree near his house; another shared that there was a tree like Steve in her family and it was at this very tree where her grandparents met each other. Still another said that his first toy, a wooden duck, was something close to his heart from nature because it was made from the trees in El Salvador.

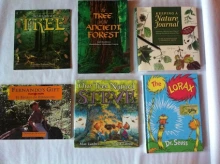

The children each chose a tree to observe over the year and our nature walks became an important part of our program. By connecting our walks to our reading our texts took on new meaning. The Tree in the Ancient Forest (Jones-Reed, 1995), a book about an ancient forest, began to make sense to the children when they noticed a tree with a plaque that read “planted in 2002”. They recognized that this tree was nowhere near the height of full-grown trees that surrounded it. By pairing this book with The Lorax (Geisel, 1971), which invites readers to consider a world without trees, the children explored issues of logging, deforestation and regeneration.

Our discussions flowed from personal perspectives to global perspectives as we introduced texts and literacy engagements to support the children in understanding the interdependence of people, trees and the health of our planet. In The Great Kapok Tree (Cherry, 1990) the tree is referred to as a tree of miracles. Illustrating their developing understanding of some of the ways people are connected to trees they explained that it is a tree of miracles because it provides home for the animals and gives us fruit and products that are derived from trees like medicine, gum, and syrup. Yet, when tracing the connections of animals to trees and negotiating the needs of animals versus the needs of people a them versus us debate ensued. Moving from personal perspectives to global perspectives often paired our reading of rich literature with nonfiction texts. In response prompts like “If your tree could talk what would it say? How is it feeling?” the children had to consider the weather and time of the season by bringing in nonfiction texts to support their personified responses.

As our in-depth study began to conclude we focused on a line from The Lorax, “We speak for the trees.” For our culminating project, the children considered the question, “If you could speak for the trees what would you say?” as they designed brochures. For their brochures they developed a slogan from the perspective of trees and included information to support their position. Some of their slogans included: Use a tree, plant a tree; Plant a tree every time you cut one down; If you cut down a tree, use it wisely, and Trees make us healthy. Sketches and photographs of their trees created during our nature walks were available to add illustration.

Critically thinking with our students about our global relationship with nature and inviting them to respectfully consider different perspectives, listen and offer creative solutions empowered these bilingual learners to find and share their own voices. Teaching for global relationships with nature using rich children’s literature as our primary tool brought the joy of awakening our students to new understandings.

References

Cherry, L. (1990). The great kapok tree. San Diego, CA: Voyager Books/Harcourt.

Geisel, T. S. (1971). The Lorax. New York: Random House.

Jones-Reed, C. (1995). The tree in the ancient forest. Nevada City, CA: Dawn.

Keister, D. (1995). Fernando’s gift: el regalo de Fernando. San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club.

Zweibel, A. (2005). Our tree named Steve. New York: Penguin.

Liza Carfora was a literacy specialist at the Reading/Writing/Learning Clinic at Hofstra University and is now teaching third grade at the Spruce Street School in New York City.

WOW Stories, Volume IV, Issue 3 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/iv3.