A Rocky Road from Disaster to Dialogue and Back Again: Literature Discussion Over Time

By Amy D. Edwards, Fifth Grade, Van Horne Elementary, Vignette 3 of 3

Teachers at our school work collaboratively with our Instructional Coach, Lisa Thomas, in a setting we call the Learning Lab. Classes come to the lab once a week for a lesson and then work on connected areas of study while in their regular classrooms. Kathy Short, a university researcher, participated in the lab one day a week and was part of the interactions with my class.

Our focus this year in the lab has been literature discussion, with our particular goal to teach students how to engage in meaning-centered thoughtful talk about their reading and how to move their discussions between conversation and dialogue. Conversation involves sharing their initial responses and connections and so the talk goes in many directions and is often tentative without careful listening to each other. We know that conversations are an essential part of a discussion because students need to share this wide range of connections to find issues that are tensions that they want to pursue in dialogue. Dialogue requires that students have a focus that they are inquiring about together and that they listen to each other’s ideas and give consideration to those thoughts in their own comments (Short & Harste, 1996). As hard as we try, sometimes teachers struggle to achieve these goals even with their best efforts and support from other professionals.

As a classroom teacher I wanted to move away from teacher-led discussions where students passively waited for my questions. These discussions almost always resulted in conversations that did not go deeply enough or focused on the story elements and not the larger conceptual issues in the text. Conceptual issues enable us to think abstractly and to develop interpretations (Santman, 2005) taking conversations to a deeper level, thus shifting it into dialogue. But first students had to learn how to talk about books in a format that differed from the ones they were used to, such as raising their hands to speak. Teaching, engaging in talk, and debriefing the process of discussion were necessary for this goal to be accomplished (Noe & Johnson, 1999). Literature discussions depend on students’ willingness to talk about the connections and tensions that really matter in their lives and so it was also important to set up a classroom where students felt safe to do so.

A Rough Start

Our first literature circle in August was not a discussion. It was a disaster. In the lab they listened to a story about a practical joke that we thought kids would enjoy and easily make connections to. The students struggled to get started. They began sharing personal stories right away but were talking on top of each other with side conversations going on around the room. It was as if we had never engaged in a literature discussion in our classroom at all. I think that the students’ sense of place and expected behavior was confused between the lab and our classroom.

We reminded them that this was a whole group discussion, not small groups as they had been doing in the classroom. They started again, but the side talk and talking on top of each other continued. Finally one student spoke, saying loudly that she thought they were supposed to be working as a group. Conner tried to facilitate by asking who wanted to go next as they had been coached in class for small group settings. Students were trying to shush each other and suggesting that they take turns.

It was sad and embarrassing that they had to resort to formal procedures in an attempt to have a discussion. They seemed to have learned that procedure matters more than what others were saying. I could see that my firm procedures in the classroom would have to be set aside when it came to literature circles.

Maddy suggested that they take turns and go in ABC order by their names, which they did, using student numbers to determine order of sharing. Students’ comments were limited to retelling the story or memories but they made no connections to each other’s comments. Some students choose to not comment at all. Others forgot what they were going to say by the time it was their turn. Some students just enjoyed the limelight and seemed to be performing for others. When they got through the whole order students began raising their hands to talk. Brody suggested they use the “popcorn” strategy we use in our classroom to choose a new reader where the person who shares chooses the next person to talk from among those who have their hands raised. Students complained that some people had had several turns already. This was not a discussion. Students were having a very controlled conversation that wasn’t even close to becoming a dialogue.

In debriefing with students, it became apparent that they thought that having a conversation with a large group was difficult. They agreed that going in alphabetical order was too hard. Students were frustrated because some people shared three times and others didn’t get to share at all. Lisa asked them what they do at lunch and how they know when to talk. Ashleigh responded that they just talk when there’s room, “The conversations are all around and you just jump in.” The students felt that it was easier when there were fewer people trying to talk with each other. Some students said that at lunch they all talk at the same time like they did today. We asked the kids to research how people talk in different locations and situations before our next meeting.

The next time we met in the lab students listened to The Recess Queen (O’Neill, 2002). As a whole group they started right in with number order again in their sharing. There was lots of talk about the book and about the theme of bullies. There were some connections but many important ideas were just passed by when others made comments that were unrelated as they took turns sharing. When Preston said that you can change people no matter how mean they are, no one picked up on his idea. Each student just made a comment and moved on to the next person’s turn to comment. They seemed to view literature circles as everyone getting a turn to talk but without any responsibility to build from each other’s ideas or to collaboratively think with each other.

After giving them a chance to share, Lisa started webbing their ideas about the book and that’s when the discussion became more natural. With some guidance, students shared their stories and connections as Lisa drew out the big ideas behind those stories. This was done to encourage students to dig deeper in order to move their discussions from conversation to dialogue. We knew that they would need to find a larger issue that they could focus on together for the shift to occur and move them beyond sharing stories to discussing issues. This was a start. Now we just needed to lose the number order this class felt compelled to use to get their discussion started.

Developing Tools for Our Journey

In our classroom, I reviewed the discussion methods from Getting Started with Literature Circles (Noe & Johnson, 1999) that had been introduced in August. I had focused on teaching students how to talk with others about books in ways that invited their participation around increasing their understanding of the book. Our class brainstormed ideas on guidelines for conducting a good discussion. Students came up with ones similar to those proposed in the book. This time I wrote the guidelines on poster paper to be hung in the classroom. They included:

- Get started in one minute after moving to your discussion space.

- Be ready to discuss when you come to the group.

- No reading ahead.

- Listen to one another.

- Share your ideas.

Students used these guidelines throughout the week in our small group literature circles in the classroom. I also introduced some response tools (Noe & Johnson, 1999) to help keep a discussion going. These included:

- Using sticky notes to mark important parts of the story.

- Using bookmarks that were large enough to record pages of interest.

- Using literature logs to record wonderings, golden words, and personal connections.

The following week in the lab, the students listened to Be Good to Eddie Lee (Fleming, 1993), about a boy with Downs Syndrome who is being teased. Lisa explained that they were going to work on connecting their responses to big ideas and would use quick writes and small group literature circles so that it would be easier to have a conversation about the book. The quick writes helped students get ready to share, cemented their thinking and gave them something to build on as others shared. The small groups seemed to be more beneficial, because these kids often controlled or monopolized conversation.

The first group that I observed talked almost exclusively about the frog eggs in the story. One child said he didn’t like when the other kid said something mean to Eddie Lee and that it was a nice story. That comment went unacknowledged. The three remaining boys at the table continued their talk about frog eggs.

Another group wondered why Jim Bob didn’t hang out with other kids. They noticed that he was mean to Eddie Lee. One student made a silly comment about naming a kid Jim Bob. This was the kind of comment that gets conversation off track, but luckily the others stayed focused on why the children were mean to Eddie Lee. Taylor wondered, “What’s so different about him?” to which Sydney replied, “Being different is sometimes fun.”

I noticed that kids were using the strategies we learned in class to get the conversation going in their small groups, such as “Who wants to start?” Also when the conversation lagged I heard someone ask if there was anyone else with a comment. Things progressed nicely.

As the students moved the discussion to whole group many more ideas were shared and connections were made. Big ideas that were webbed included:

- Not treating others badly because they are different.

- Standing up for each other.

- Not judging a book by its cover, or a person by their appearance.

- Getting to know someone is sometimes different than what you expect.

- Good for everyone to be different.

- Do not take tadpoles away from their habitat.

Their ideas were still going in multiple directions and were sometimes off topic—a reflection of the fact that they were being typical fifth graders. At least they seemed to be more engaged in talking with each other rather than at each other.

In debriefing, students were asked how their talk helped their thinking. They responded that students kept adding ideas and comments that they might not have thought of on their own. They recognized that when someone commented, it helped them think of something new. They felt that more people needed to get into the conversation because some people did not share at all.

They did a better job of turn taking without formal procedures; however, there were still some problems. They recognized that they went off topic at times. In comparing the small groups to the large group, students said that in the small group there were not as many ideas but it was easier to listen. In the large group, there were more ideas but it was harder to listen. Still, it was the end of September and they were making progress.

Crossing Fences and Bridges

A turning point in making real progress with literature discussion occurred as students responded to The Other Side, by Jacqueline Woodson (2001) in the lab during October. This book is about the developing friendship between two girls, one black and one white, while sitting on a fence that racially separates their town. During the discussions of this book, students made the transition from conversation to dialogue, meaning that students were thinking more deeply and in conceptual ways about issues that were genuine inquiries, rather than just sharing comments on topics. This didn’t happen overnight, but evolved slowly over October and into November. Our goal was to help students be able to sustain and focus their talk as they inquired around one issue rather than just naming topics or ideas in the texts. We supported students’ thinking with quick writes, consensus boards, webbing their wonderings, and revisiting the text several times. We also arranged a wide reading opportunity for students to explore a text set of picture books dealing with black/white relationships throughout American history because they had some confusion about this history to sort out. The consensus boards were large sheets of paper with spaces where students could individually draw or write about their personal connections and a large center circle where they could write their continuing tensions or questions after sharing their connections.

During their discussion of The Other Side, the class concluded that the fence was a symbol of what separates people. In the following weeks students used the term “fence” while discussing other texts that they thought included divisions between people. This was an important shift in thinking for my class. They were so interested in this concept that we put together a text set of picture books with all types of symbolic “fences” that students had a chance to read and discuss to broaden their conception of the issues that divide people. This concept of a symbolic fence gave the students a framework for their thinking and showed that their connections reached way beyond the book itself. This was definitely progress.

Throughout the year in our classroom there were four literature circle groups with each group reading a different book related to our class focus. The structure for discussion was for all of the groups to meet at the same time while I visited each group as an observer and facilitator. I would journal about what the students were talking about and how the discussions were going as I visited each group. Students had to agree on the number of pages to read each week, could not read ahead, and were to develop a response tool to support their discussion, such as sticky notes, bookmarks, or logs. Occasionally I set up a tape recorder so that I could later listen to whole conversations. I usually started the session with a reminder of the discussion guidelines and ended with a debriefing session.

By the end of November, the literature circles in the classroom were running smoothly with a few interruptions from students who had a hard time focusing on the task at hand. We read books that integrated the social studies curriculum with the reading curriculum, and so our books were novels about the Revolutionary War in the U.S. The students were adept at keeping the discussion going and making connections. At times it was like watching adults discuss in a literary book club. At other times, it was a challenge to keep certain kids from playing with the tape recorder. Overall, these groups were running smoothly and the discussion strategies that they were displaying in class were carrying over into the discussions in the lab. Students were taking turns in a natural way, building on each other’s ideas, and finding symbolic meanings that transcended texts.

In late November our team decided to do a read aloud using Seedfolks, a short chapter book by Paul Fleishman (1997). We chose this book because it had a variety of significant social issues, including love, loss, death, sickness, learning to speak English, immigration, teen pregnancy, friendship, and caring for others. Each chapter is told from a different character’s point of view about their work in an urban garden in a crumbling neighborhood. The garden brings all of the characters together despite differences. Each day in my classroom, I read aloud a chapter and students responded in their literature logs using sketch to stretch, webs, or quick writes.

The first discussion was held in the lab and went well considering that this was a new book and they had only heard the first chapter. This chapter focused on Kim, a young girl who misses her father, who died before she was born. Kim reveals that her dad had been a farmer and she decides to plant six lima beans that the family had saved to connect to him in some way. The students had a lot to say and were curious about how Kim’s father died. Interestingly, since Kim was from Vietnam, they thought her father might have been killed in the war. They had a hard time with the chronology of historical events, but they were trying. They immediately identified the “fence” in this chapter as death. They saw the connection between planting and Kim’s father, and kept trying to make sense of the six seeds and to attach significance to the number six.

In December discussions continued as we tried to avoid the fact that the holidays and winter break were approaching. The students were on a roll and I was determined not to let anything interfere with the progress they were making.

One particular discussion that stood out was about the chapter on Maricela, a pregnant sixteen-year-old girl who did not want her baby. They identified with Maricela wanting to have fun but could not believe that she wanted her baby to die. I was concerned about discussing the issues in this chapter as this topic was not one kids were used to addressing in a school setting. I was amazed at how remarkably mature ten- and eleven-year-old kids could be when you least expect it. I got a sense that they were surprised we were talking about such issues in school, but they took the challenge head-on and their tension about Marciela’s attitude toward her baby moved them into dialogue.

Conner said that he got a true sense of how Maricela was feeling right from the start when she introduced herself and said, “Just shoot me.” He noted, “She thinks her life is over.” Other comments flowed as students shared their thoughts and connections. Taylor shared that her parents told her she would ruin her life if she had a baby before she was 25. Brody thought that Maricela’s parents must be mad at her. Natali talked about high schools where girls could put their babies in the day care center so they could finish school, but wondered how she would go to college with a baby. Christopher thought that maybe she would put the baby up for adoption. Clearly these issues that had been discussed at home with their parents.

Maricela worked in the garden as part of a teen motherhood program. At first she was uninterested in the garden but soon realized the connection between nurturing the plants and keeping her baby. Evan recognized that learning to care about plants made her want the baby more. Ashleigh shared that at first Maricela thought that the baby would ruin everything, then later after working in the garden, realized that her situation wasn’t so bad after all. Esperanza noticed that Maricela was upset and angry about the baby, but that growing the plants gave Maricela faith to have her baby and made her think about playing with it and watching it grow up.

As the students talked about the change in Marciela’s attitude, they commented on the connection that the garden had on the other characters as well. Conner noted that so far everyone in the story was connected by the garden, saying “The garden made everyone feel better and they all had problems to ‘plant.’ As they watched the plants grow, their problems seemed to be worked out somehow.” Evan noticed that in each chapter there was someone who was angry about something. He suggested that the garden was an antidote for problems. Kaitlynn commented that all of the characters were of different nationalities and skin colors and that the garden brought them all together. Brody argued they were separated by their cultures. He said that maybe in the end they would realize they were not really different. Students recognized many “fences” in the story and Conner took this metaphor further when he said that the garden was a “bridge” for everyone, saying, “The garden connected them all because the plants made a bridge to help them solve the problems that they had in their lives.”

A Curve in the Road

The discussion seemed to be developing well around these issues, but as students became more excited, things started to fall apart. As we were brainstorming ideas for responding to the book through art, students started to talk on top of one another. They had trouble waiting to push into the conversation and being heard was difficult as the kids struggled for control. Lisa stopped the group and discussed the problems they were having. They were talking on top of each other, not listening to each other, and they were thinking of what they were going to say when they did get a turn instead of connecting to others’ ideas. We noticed that some students dropped out of the conversation and others kept pushing in to get their way. Kathy commented that it felt like a competition.

The kids discussed some possible solutions. For some reason, they suggested turn-taking procedures like they had done at the beginning of the year. Kathy indicated that they needed other ways to solve the problem because those procedures didn’t fit the kind of discussion we were engaging in around books. We kept brainstorming and listed suggestions from both kids and adults in the room:

- Leaving a silence before the next person talks.

- Look at the person who is talking, so you know when they are done talking.

- When someone has an idea and others have the same idea, connect the two by saying, “My comment connects to so and so’s.”

We moved to the art response and hoped that the breakdown in their ability to discuss meaningfully with each other would not be a problem in the future. It was frustrating to see this happen to students who obviously had many great ideas and wonderings and who had been engaging in productive discussions for months. I guess we had to admit that it was time for winter break.

When we returned from winter break in January, I noticed that students were still having a hard time staying on task. I reviewed our guidelines for a good discussion and appropriate ways to respond and encouraged students to use response strategies that had been successful in the past, such as sketch to stretch and graffiti boards. The first semester the students loved using graffiti boards, a shared piece of paper to record pictures and words about their “in process” ideas and thoughts on a book. They also had earlier made powerful use of sketch to stretch, a reader-based response in which students create a graphic or symbolic drawing of what the story means to them. This is not meant to be an illustration of the story but rather the meaning they are constructing for the book. Students then share their sketches in small groups, letting others comment on the meanings they see in a particular sketch before the person who created the sketch shares the meaning he/she had been thinking about (Short & Harste, 1996). Even with these response strategies, their discussions remained loud and unfocused in our classroom.

A Change of Scenery

In January, we started a study of culture in the lab and engaged students in exploring their own cultural identities. We felt that for students to understand other cultures, they must first understand the significance of their own cultures in their lives. In January and February, discussion of literature was not a big part of this process and students completed other activities to work toward our goal of intercultural understanding.

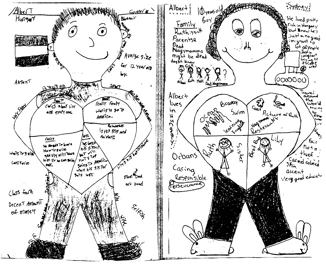

Cultural X-Rays are pictorial representations of who we are culturally. Because culture is multifaceted, it is hard for students to understand the many characteristics of our cultural identities. This strategy demonstrates culture to students in a visual way so that students can build an understanding of culture as they are completing the X-Ray. Using a simple outline of a person’s body, showing a large heart in the center, students draw pictures or write words outside the body to tell what we are. We listed possible characteristics so that students had a sense of the nuances of some of the influences on culture, such as language, family structure, age, race, gender, nationality, education, country, state, city, area of the city, religion, social class, family heritage, and the kind of neighborhood you live in. Inside the heart students show things they value and why they value those things using pictures or words. Things that are most significant are shown larger than others. Finally, students decorate the body outline to look like themselves, showing hair, facial features, and clothing. This strategy was helpful in teaching students about culture in a way they could construct for themselves. Once they had represented themselves, they used this strategy to explore characters in texts they were reading.

In the short discussions we did have, students had a tough time listening to each other. I wondered how a group who had it so together in making discussions meaningful earlier in the year could fall apart when they had support in both the classroom and the lab. They had made such strides that this downward spiral was disappointing.

Are We There Yet?

In March students started an inquiry study in the lab. Students researched an aspect of Korean culture in which they were interested, as well as participated in read alouds around a historical fiction novel, When My Name Was Keoko, by Linda Sue Park (2002). They had the opportunity to meet a young Korean woman to interview her about contemporary Korean culture and to learn a bit about Hangul, the written language. They also listened to her read Korean books so they could get an idea of how the language sounded. Later, she came back and answered questions about everyday life in Korea.

In the lab, students did wide reading of many picture books about Korea, both in English and Korean. After browsing these books students shared the things they noticed:

- Korean children were entertained differently. Here we used a lot of violence for entertainment, there they used people and animals.

- They had royalty.

- Illustrations in the books were different, more abstract and creative.

- They kneeled and ate at small tables.

- Clothing seemed mostly the same.

- Even if the books were written in Korean, they could tell what was happening.

- Family structures were similar.

- Children in Korea wanted to do the same work as their parents or grandparents.

In the discussion it was obvious that the kids were excited about the books. They talked about the bigger ideas and didn’t just focus on the details; however, certain kids still dominated the talk and a lot of them pushed to get into the discussion by talking the loudest. It was competitive. As this happened others sat back, and so not as many students were involved in the discussion. As adults we wondered why this was happening. Part of the problem was likely due to the unpredictability and social dynamics of eleven-year-old kids about to be promoted to middle school. Another factor was that this group of students was particularly bright and perhaps not used to having to think with peers about issues because they always knew the answers on their own. We were asking them to unlearn habits they had developed in six years of school and to change their perspectives about each other’s contributions to their thinking. We found ourselves starting each discussion in the lab reminding students to listen to each other and build from the comments of others.

The Korean inquiry was carried over to the classroom where students were gathering information to complete a collage demonstrating what they had learned from their individual research. At this time, students engaged in whole group discussion as I read aloud Keoko. The book contains two voices, a brother and sister, thus giving both the male and female perspective on the Japanese occupation of Korea right before WWII. The chapters alternated between Sun-hee and Tae-Yul and so we read two chapters a day to include both perspectives of the same events.

Still Off-Track

When we attempted a whole group literature circle in the lab about two of the chapters, the discussion was so disastrous that we had to stop and talk about the frustrations. Students came up with ways to solve the problem, including:

- Save the discussion for the classroom because they need more time to talk.

- Avoid using outside (loud) voices.

- Make sure you connect your thinking to that of others.

- Don’t try to be funny to entertain and make others misbehave.

- Make time for everyone to speak.

- Pause before rushing in on someone else’s talking.

- Share one person at a time.

- Don’t talk loudly so others will back down.

- Pick someone to start.

- Write thoughts in class, and then discuss them in the lab.

Students knew how to conduct a discussion. It was so frustrating to see this happening. I strongly felt that part of the problem was that the students felt a time constraint in the lab. We also had some bright students with strong personalities who did, when pressed, identify themselves as tending to dominate the discussions. I later spoke privately with these students and asked them to be considerate of the others in sharing the talk time. I also believe that some students were trying to show off for Lisa and Kathy. We kept trying though, and eventually it paid off.

Meanwhile students continued with small group literature circles on Civil War historical fiction novels in our classroom. While conducting these discussions things had returned to a productive status as groups discussed Shades of Gray (Reader, 1989), Numbering All the Bones (Rinaldi, 2005), Bull Run (Fleischman, 1993), and Lincoln: A Photobiography (Freedman, 1988). Student were doing a good job of taking turns, connecting comments and gaining a lot from what others had to say about these books. In an effort to keep the discussions fruitful, I pointed out whenever the process was working well for them.

On the Road to Success

A breakthrough came at the end of March when discussing My Freedom Trip (Park & Park, 1998) in the lab. It was a story about a girl and her father who escape from North to South Korea but are separated from the mother who is never able to make it across the border. The separation of the girl from her mother caused real tension for the students because they expected a happy ending. They made connections with other texts and to each other, allowing some new voices to be heard. Students who had previously dominated, only shared once. It was a relief to see that they were taking to heart all of the work we had done to get to this point. I knew that this group was smart enough and had made some brilliant connections with symbolic language and meanings earlier in the year, but was frustrated with the lack of consistency in their ability to consistently manage a constructive discussion. Things were definitely looking up.

As we continued the discussions throughout the remainder of Keoko, the students continued to thoughtfully approach their responses. Literature logs showed deep thinking about the issues in the story. Students made many connections to other books we had read that were set in the same time period, such as Lily’s Crossing (Giff, 1997). And because of the work they had done with their own Cultural X-Rays, they had a better understanding of the culture in which the book takes place.

The research projects that they completed were detailed and thoughtful. Students gained new understandings about Korean culture and continued to have more questions that interested them. Students who researched the same topics shared in small group settings and gathered even more information before sharing with the whole group. All of this information assisted in understanding Keoko and the Korean culture. It enabled students to not only understand the similarities and differences in our cultures, but they recognized that different cultures weren’t strange and started understanding the concept of different perspectives. When a student commented that something was weird, Ashleigh piped right up saying, “That’s not weird from their perspective. They probably think what we do is weird.” That was when I knew that they were becoming aware of not making judgments from their own cultural perspective. Our study in cultural understanding of Korea was successful. Discussions were back on track and students were gleaning deeper understandings of our world as whole. My faith in this group had been restored, and we ended the year on a high note. It was a long bumpy road, but so worth it.

Literature circles should actively involve students in critically considering their differing interpretations of a book and in working through their personal transactions with literature (Rosenblatt, 1978). The heart of why writers write and readers read is to actively engage in thinking about issues that matter in their lives and world. Encouraging readers to discuss their ideas with others deepens understanding and opens new thought processes in ways that solitary reading cannot begin to promote. Having conversations about books where students share initial responses and connections is necessary to a successful discussion but conversation alone is not sufficient. Students need to move from conversation to dialogue where they focus on thinking together about issues and tensions that have significance for them. Through dialogue, they engage in critical thinking that is transformative, taking them beyond their current selves to new understandings and perspectives, both of themselves and of the world.

Resources

Fleishman, P. (1993). Bull Run. New York: HarperCollins

Fleishman, P. (1997). Seedfolks. New York: HarperCollins.

Fleming, V. (1993). Be nice to Eddie Lee. New York: Putnam.

Freedman, R. (1988). Lincoln: A photobiography. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Giff, P.R. (1997) Lily’s crossing. New York: Scholastic.

Noe , K.S. & Johnson, N. (1999). Getting started with literature circles. Norwood, MA: Christopher-Gordon.

Park, F. & Park, G. (1998). My freedom trip. Honesdale, PA: Highlights.

Park, L.S. (2002). When my name was Keoko. New York: Yearling.

O’Neill, A. (2002). The recess queen. New York: Scholastic.

Reader, C. (1989). Shades of gray. New York: Simon & Shuster.

Rinaldi, A. (2005). Numbering all the bones. New York: Hyperion.

Rosenblatt, L. (1978). The reader, the text, and the poem: The transactional theory of the literary work. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Santman, D. (2005). Shades of meaning. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Short, K. G. & Harste, J. (1996). Creating classrooms for authors and inquirers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Woodson, J. (2001). The other side. New York: Putnam.

WOW Stories, Volume I, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesi1.