Extending Thinking: Literature Response through Art

By Amy D. Edwards, Fifth Grade, Van Horne Elementary, Vignette 1 of 3

As a teacher, I am always looking for new ways to encourage my fifth graders to extend their thinking and to further explore what they have learned. It is important to me that they be responsible for their learning and not dependent on me to challenge their thinking. Response to literature can effectively do this through the arts, including visual art, music, drama, and language. Responding through art allows students to think symbolically about what they have read by representing their thinking in a whole new sign system (Peirce, 1966). By moving from language to art, music, or drama, they create new connections and meanings, open new lines of communication, and are encouraged to question their understandings (Siegel, 1995).

One way to facilitate thinking is by having students do a Sketch to Stretch, which is a reader-based response where students are asked to create a quick graphic or symbolic drawing of what the story means to them or of connections that they see as significant related to the book. This sketch is not meant to be an illustration of the story but rather focuses on the meaning constructed in the reader’s mind. Students then share their sketches in small groups letting others comment on the meanings they see in the sketch before sharing their own interpretations (Short & Harste, 1996).

I chose to introduce the Sketch to Stretch strategy for specific reasons. This strategy encourages students to deepen thoughts about ideas in literature and to respond in symbolic ways. I wanted my students to think about the themes and concepts in the books rather than simply tell their personal stories related to the book and to be able to think at a symbolic level. I chose the short chapter book Seedfolks (Fleischman, 1997) as a read aloud because it has a variety of topics and broad concepts that students can respond to. Each chapter is told from a different character’s point of view and is about a decaying neighborhood in which a garden brings all of the characters together despite many differences. The book is full of rich concepts reflecting difficult life issues, including immigration, poverty, love, death, teenage pregnancy, and caring for others. Each day a chapter was read aloud and students responded in their literature logs made especially for Seedfolks. This was done by stapling blank paper into a folded 9 x 12 piece of construction paper to serve as a cover.

After each chapter was read aloud, students recorded their connections and ideas. Students responded in any way they chose and responses varied greatly, sometimes in the form of a quick write and at other times a drawing or a web. If symbols were chosen to represent meaning, students were encouraged to show importance by making drawings larger if they represented something more important and smaller for things less significant. It was evident that some students gained more meaning through these multiple opportunities to respond visually. The drawings seemed to stimulate new thoughts and understandings.

In looking through the students’ literature logs I noticed connections and ideas that may not have come up in a routine question and answer situation. Their responses were more thoughtful and seemed to build meaning in a new way for each student. Ashleigh responded to the chapter about Leona, a woman raised by Granny and her Goldenrod tea, who showed tremendous patience and perseverance in getting the city to clean up the “vacant” lot. She wanted to plant goldenrod tea but couldn’t stand the trash dumped in the lot by others who thought they wouldn’t care because they were such slobs down in that neighborhood. She knew others would want to plant too, but not until the lot had been cleared. She called everyone in city hall that she could think of, and when that didn’t work, brought a bag of the vile smelling stuff to city hall to prove her point. It worked. Men in jumpsuits sent from the jail cleared the lot. Leona never gave up hope. Ashleigh’s sketch shows the road to happiness. The message she wrote is that hope takes you great distances. The garden in the story gave many of the characters great hope.

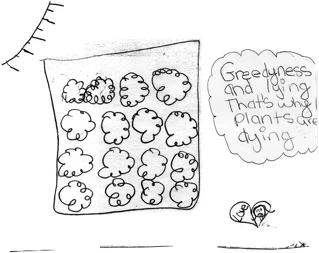

In the chapter about Virgil, a fifth-grade boy tells of his father’s greed. Virgil’s dad drove a cab and had cooked up a scheme to get rich by growing baby leaf lettuce and selling it to fancy restaurants. The two dig up a plot of land four times bigger than anyone else’s and plant the tiny seeds only to have the crop fail due to hot weather. When Virgil’s teacher asks why they have taken up so much land, Virgil’s dad says it is for the extended family. Virgil knows he is lying. Ashleigh’s sketch shows that greed and deceit were the reason the plants died.

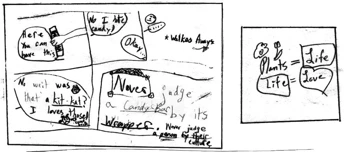

Rachel created a sketch to reveal what she learned about Amir. Amir, an Indian who is uncomfortable living among so many strangers in America, believes the garden’s greatest gift is the ability to see one’s neighbors. His eggplant’s unique color allows his neighbors to break the rules about avoiding others and invites them to start a conversation. He talks about his immigrant neighbors and the stereotypes he had come to believe about each group. His conversations with his new friends dispel his false beliefs. Amir is a shrewd businessman, trained to give away nothing, to always make a profit. The garden encourages him to break that rule by sharing the harvest. He recalls an Italian woman who admired his eggplants and told him how to cook them. As they share stories about their families, he suddenly realizes that she is the same woman who accused him of giving her the wrong change at his store the year before. She called him “a dirty foreigner” even though she also has a strong accent. He reminds her of the incident, and she apologizes, saying, “Back then, I didn’t know it was you.”

Rachel drew a picture of someone being offered a candy bar. The person declines, saying, “No, I hate candy!” Then they reconsider saying, “Was that a Kit Kat bar?? I love those!” She ends with the message, “Never judge a candy bar by its wrapper. Never judge a person by its culture.” She adds a picture on the next page showing a mathematical equation that says, “Plants =Life, Life=Love.” This student clearly had gotten deep meaning from this story and was able to show her understanding through words and symbols in a way that is both clever and surprising.

After completing the book we worked on artistic responses using watercolor. Students created a sketch to stretch that represented the central meaning of the story for them. As a whole group, students brainstormed messages from the book. Many students looked through their literature logs for reminders. Some of the meanings students came up with were:

- The garden is a symbolic friend.

- Love solves all.

- Caring for the Earth and its people is like a chain reaction.

- When you set a good example, good things happen.

- Planting is life, planting gives life.

- Working together despite our differences.

I showed students four ways to visually represent the meaning of Seedfolks in their watercolors. They could demonstrate a personal connection, create an abstract image, use a mathematical equation or develop a thematic depiction to demonstrate what the book meant to them. They were asked to accompany their artwork with a message or to choose a quote from the book to put alongside the artwork. We then shared these watercolor sketches in small groups using Save the Last Word (Short & Harste, 1996) before all pieces were displayed in the hallway as a gallery collection.

Matthews’s watercolor shows the garden as a symbolic friend through a plot of ground shaped like a person with plants growing all over the body. The garden’s hair is represented by asparagus; its ears are ears of corn, and a carrot serves as its nose. The “garden” is holding hands with two friends. His message says that the garden is like a symbolic friend who helps other friends with the troubles they have. His sketch is bright and beautiful and conveys Matthew’s thoughts in a way that expressed his understanding.

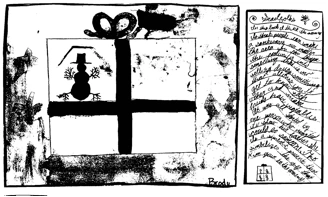

Brody beautifully painted a picture of a wrapped gift or present. He saw the meaning of Seedfolks as a symbolic present that the first character, Kim, who planted the six seeds, gave to the community. Kim planted the seeds in memory of her father, who was a farmer. Brody says in his message that the garden allowed people to shape the community into something positive and not as a place for selling drugs or for crime. The garden allowed the neighbors to get to know each other, make friends, and share their vegetables. He calls the garden a sanctuary for the residents to shape into something good. Creating this sketch enabled Brody to understand more fully the meaning of the text. He was able to create meaning through art that may not have been captured through language.

Kaitlynn’s watercolor shows colorful flowers surrounding a red flower in the shape of a heart. The flowers are all different shapes and sizes representing different types of people in the world. The green wash of color surrounding the flowers represents life. She says the flowers are all unique, a lot like people. The heart shaped flower in the middle represents “Love”, because love can do a lot for the world. This illustration goes beyond a literal understanding of the text. Kaitlynn used transmediation (Eco, 1976) to recast her understanding of the text by moving from the understanding she made in one sign system and transferring it into another, in this case from language to art.

When the gallery was complete, students took a gallery walk to see the work of their classmates. We sat in the hallway to get a chance to explore and let students share their thoughts with each other. It was the best culminating activity I had ever had a chance to experience with my students. Their watercolors were a great way to sum up the learning that occurred. Doing the gallery walk was very special and made the students feel like real artists. The students were proud of their work and felt valued, knowing that everyone appreciated their unique perspective. There were no right or wrong responses.

Response to literature starts with negotiation and conversation that leads to dialogue. Students need to engage in discussion with others to gain meaning through building on others’ ideas and interpretations. Talking about the text facilitates meaning making with the goal of creating and critiquing their understandings, not with coming up with the same interpretations (Short & Kauffman, 2004). Art as a response supports readers in showing what they know in another sign system and in a way that others may not have considered. Thinking through different sign systems to make and share meaning is an important facet of literature response and part of what makes us uniquely human.

References

Eco, U. (1976). A theory of semiotics. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Fleishman, P. (1997) Seedfolks. New York: HarperCollins.

Pierce, C. S. (1966). Collected papers. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Short, K. G. & Harste, J. (1996). Creating classrooms for authors and inquirers. Portsmouth, NH: Heineman.

Short, K. G. & Kauffman, G. (2004). Examining prejudice through children’s responses to literature and the arts. Democracy & Education, 15(3-4), 49-53.

Siegel, M. (1995). More than words: The Generative power of transmediation for learning. Canadian Journal of Education, 20, 455-475.

WOW Stories, Volume I, Issue 1 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesi1.