Conceptualization as a Way of Thinking in Schools

by Lisa Thomas, Instructional Coach, Van Horne Elementary School

Learners need to think conceptually to develop insights into their world through the stories that they read. They need to be able to go beyond the specific story events, context and characters to dig deeply into broader issues and ideas. Dewey (1938) argues that without this type of reflection, their thinking is not taken to a higher level to become an organized part of how that learner approaches and thinks about future experiences.

The teachers at Van Horne have worked to support elementary students in recognizing and accessing their ability to think conceptually. Our struggles with supporting this type of thinking have led us to realize that conceptualization is a broad umbrella of thought that grows out of the complex integration of different types of thinking. We want the adults and children at our school to be conceptual thinkers, and we have worked to encourage this thinking in a variety of ways. We know that people, young and old, naturally think conceptually. This kind of thinking is required to learn and function in our world. Our challenge has not been in teaching and learning how to think conceptually, but instead in understanding this thinking in a way that allows us to recognize and access it to support our learning in the school setting where it is often underutilized.

We didn’t want to emphasize isolated elements of thinking (spending one week on synthesis, another on symbolic thinking) in a way that would move us away from the flexible coordination and collaboration of real thought. Nor did we want learners to be challenged occasionally and randomly in “higher order thinking” through a series of pre-crafted, teacher created questions. We wanted this type of thinking to be connected, continuous, meaningful, and natural.

Much of our reflection and planning time during the past school year was spent gathering and creating engagements that highlight and define conceptual thought. We chose response engagements that encourage particular types of thinking within the broader context of a unit of inquiry and then reflected as a group on the kind of thinking that occurred. This allowed the learners the chance to be more aware of their thinking so that they could pull from it as a resource as needed. The context of experiences throughout the inquiry unit allowed learners to see the role of the specific type of thinking within the whole of conceptual thought.

As I reflected on our experiences in the Learning Lab and in study group this year, and analyzed the way that each influenced the development of conceptual understanding, two types of engagements emerged:

• Engagements that encouraged broad conceptualization

• Engagements that encouraged deep conceptualization

Before we began our work with the students, we engaged as teachers in two critical processes that set the stage for the rest of our semester. This work pushed us to think conceptually ourselves, which positioned us to support students’ movement toward conceptualization. These processes involved deciding to work from a broad concept as an organizer across our school and meeting in a retreat to develop our own conceptual understandings of that broad concept.

We began in August with teachers sharing their curricular plans for specific units of study and reflecting on why they saw those units as significant for students. After thinking about the units of study across the grade levels and considering the work we planned to do within the lab, we chose a school-wide broad concept that would connect these contexts. This focus made it possible for us to connect our work within the Learning Lab curriculum across grade levels and for teachers to connect their classroom studies with the work in the Learning Lab. It also provided a way for our arts specialist and counselor to integrate their work with classrooms across the school in more meaningful ways.

The concept of Journey became our “organizing idea; a mental construct that was timeless, universal, abstract and broad” (Erickson, 2002, p. 52). Throughout the semester, teachers and students engaged in experiences intended to help us conceptualize journey as a framework of thought to develop insights into our lives and our world. To support students in viewing journeys conceptually, we believed that we first had to develop an understanding as teachers and so met together in a retreat. Erickson (2002) asserts that “unless teachers consciously identify these understandings, they focus on the fact-based content as the endpoint in instruction, and the conceptual level of understanding is usually not addressed” (p. 49). Teachers must have opportunities to construct these meanings themselves to understand the processes necessary to support students’ explorations. Our hope was that, as teachers, our interactions with students would shift as a result of our conceptual understanding.

Developing Broad Conceptualization

Our broad explorations of journey supported us in recognizing the concept in a wide range of situations and allowed us to identify many types of literal and metaphorical journeys. We were able to see the presence of journey in our world, and to begin to develop mental definitions of journey. We did this through a number of carefully designed engagements, each building on the one before, each challenging existing understanding. Our study group time was spent reviewing the notes we had taken in the lab and analyzing student work to determine what was understood and what seemed to be missing from students’ understandings, leading us to consider what should come next--what were we (teachers and students) on the edge of understanding?

Establishing a Touchstone Text

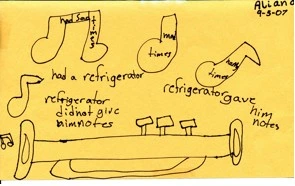

We chose The Pink Refrigerator by Tim Egan (2007) as a touchstone text, a text that we could revisit multiple times and that could serve as a common point of reference within each community of readers and across the school. We read it for the first time to introduce the idea of journey, but returned to it throughout the study and revisited it to conclude our work. The Pink Refrigerator is about a mole named Dodsworth whose life is fairly monotonous until he encounters a magical refrigerator that inspires him to try new things and take on a life of inquiry. This book explores both literal and metaphorical journeys and can be interpreted at many levels, making it appropriate across grade levels and worth revisiting throughout our study.

After discussing the book, we asked the children to map Dodsworth’s life journey from the story. This response allowed them to reflect on the story and served as a warm up for creating their own Life Journey Maps.

Connecting to Our Own Lives

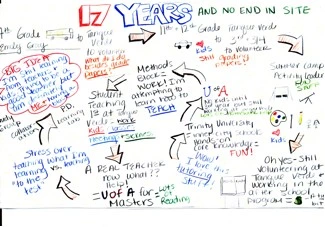

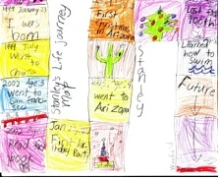

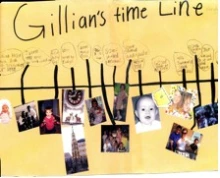

For learning to take place, we need to make connections between new experiences and what we have already experienced and understood about our world (Short, 1993). Real meaning arises when we are able to structure these connections ourselves, to interpret ideas in light of personal experiences (Peterson & Eeds, 1990). Before we could think broadly about journeys we needed to reflect on journeys within our own lives. Teachers and students engaged in mapping a personal journey. During the retreat before we began our study in the Learning Lab, teachers used the concept of journey to frame a life experience by creating professional journey maps.

Within the lab, students were asked to work with their families to create maps showing their life journeys. Both teachers and students were encouraged to be creative in representing their journeys. Some chose sequential structures like timelines and game boards, while others used structures that represented events or people in their lives as part of a whole like a puzzle piece or a heart. One student used a graph format to merge the events and the emotions in his life journey.

Exploring Metaphor

We needed to think beyond the literal definition of journey to apply a broad concept to world experiences. Students knew and understood literal journeys as vacations or trips from one place to another, but they needed to be encouraged to think metaphorically and symbolically. We also needed shared language that we could use to talk together about these new types of journeys. The term “metaphor” was introduced to children using a picture book, Once There Were Giants (Waddell, 1989), the story about a baby who grows to become a young woman with children of her own. The story begins, “Once there were Giants in our house. There were Mom and Dad and Jill and John and Uncle Tom. The small one on the rug is me.” It ends, “Then we had a baby girl and things changed. There are Giants in our house again! There is my husband, Don, and Jill and John, my mom and my dad and Uncle Tom and one of the Giants is....ME!”

It was easy for children of all ages to see that that there weren’t really giants in the story. They understood that the author was using the word “giant” to emphasize the difference in the size between the adults and the babies. This book gave us a chance to explore metaphor, an understanding critical to conceptual thinking, and helped us begin to develop a shared language as a learning community. Shared words like metaphor were needed so that we could describe, reflect on, and explain our thinking throughout this process.

Gathering and Sorting Our Understandings

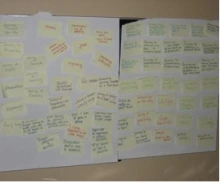

Gathering examples of journeys across a large collection of books pushed us to think beyond our own experiences--to consider journeys literally and symbolically across many contexts. Kathy Short, a researcher from the University of Arizona, and I brought dozens of books to the teacher retreat where we identified multiple journeys in the stories. Some were obvious and literal, while others were more subtle and metaphorical. We individually browsed the collection, recording journeys that we noticed on sticky notes. When we came together we grouped our individual examples into broader categories. The labels for the categories didn’t exist at this point. We simply put our examples on charts next to the ideas of our colleagues if we saw a connection. When we were through, four broad categories and two sub-categories emerged: Types of Journeys (mental and physical), Pathways of Journeys, Milestones, and Results.

As we sorted, we were able to see multiple examples of journeys side by side, noticing what they had in common. These commonalities helped us begin to define the concept of journey. We started to think past the specifics of individual examples and to ask ourselves “What can we say is true about all journeys?”

Later we challenged students to think broadly about journey in a similar fashion. Their gathering was done from their life journey maps. After they shared their maps and identified the similarities and differences in small groups, we came together to share their observations. Children made comments, such as:

• We were in Disneyland at the same time.

• We all had some sort of animal.

• Our group organized from being a baby until now.

• Me and Jose had no photos, just sketches and words.

• We were all born in 1997 or 1998.

Their comments indicated that they were thinking only about the events and the different ways those events were shown on the maps.

To push them to view their lives through a Journey lens, we asked, “How is your life like a journey?” The responses of the older children indicated their ability to generalize journey characteristics across the examples:

- We go from one thing to being able to do another thing.

- Lots of exciting things happen, sometimes good and some bad.

- If you try something new, you are experiencing things.

- You see new places and learn new things every day.

- You learn new things even if you don’t know it.

- You explore new things and keep learning and never stop learning.

- You can hurt and move into recovery. Recovery is a journey.

- Your life is a path that you choose.

- Your life is step by step.

- Pieces of a puzzle are your life. Everyday you put the pieces of the puzzle together.

Though there was some attempt to generalize, the younger children’s responses tended to be more literal and indicated that they didn’t understand what we were asking:

- We go on trips and come back.

- I caught my first fish when I went on a trip to go camping.

- We go on a trip.

- First Christmas.

Webbing and Categorizing Our Understandings

Webbing encourages conceptualization through the creation of categories and subcategories and making visible the connections between the ideas within a concept. We frequently created webs as teachers and students in the study group and lab and students often chose to use webs as a strategy for making sense of ideas on their own.

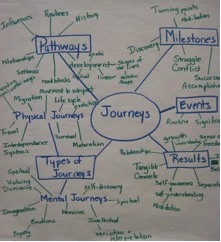

When teachers completed the charts of examples of journeys gathered from the text sets, we worked together to create a web of journeys. The broad labels from our sorting experience naturally became the main categories on our web. As we added our individual ideas to the broad categories, we thought of other examples, ideas we had not found in the books and added them to our web. Because some of the new ideas didn’t fit well into the existing categories, we had to add new categories. The webbing process helped us expand, organize, define, and better understand the concept of journey broadly.

The older students were asked to work in small groups to create a web of the kinds of journeys that they saw on their life journey maps. To accomplish this, they need to think across their Life Journey Maps and create categories and connections.

Pulling Our Thinking Together through Defining

After we had taken the time to gather, sort and web types of journeys, the teachers worked in small groups to write a broad definition of journey. We developed four definitions:

- A journey is a movement along a physical, emotional, intellectual, social or spiritual pathway.

- A journey is a series of events that have a defined beginning and end that results in physical, intellectual, emotional, or spiritual change.

- A journey is movement made of connected events.

- An individual’s path created by mental, physical, and spiritual events that often become milestones, producing a blanket of life (results).

The process of creating these definitions allowed us to bring together the ideas that we had gathered so far. While each definition is unique, they share common characteristics and demonstrated a shared conceptualization. The elements shared by these definitions reemerged frequently throughout our study and many became big ideas about journey that we explicitly explored with our first and second graders to support their symbolic and conceptual thinking.

Mapping to Conceptualize

When we began using the term journey as a label for a range of events in the world, the older children easily grasped journey as a concept and could apply it abstractly. The younger children were eager to use the term, but called everything (the desk, their teacher) a journey, indicating that they weren’t yet thinking conceptually and needed more explicit support.

We designed response maps that used common symbols to encourage key conceptual aspects of journey and asked the children to use these maps to show their thinking in response to read alouds. The picture books were carefully chosen, making sure in the beginning that the books didn’t have examples of literal journeys in which characters moved from place to place. The journeys were symbolic with one type of journey highlighted so that children could more easily explore this type of journey together.

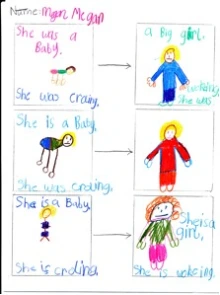

In analyzing the young children’s initial discussions of journeys, we noted that they seemed to be on the edge of recognizing growing up as a metaphorical journey. We read aloud a picture book about the change that occurs as we grow older and created a map that showed two boxes with an arrow in between. Our hope was that students would realize that journeys are not simply movement from place to place; that journeys can be events that involve change in what someone thinks and does. After reading and briefly discussing When I Was Little: A Four-Year Old's Memoir of Her Youth by Jamie Lee Curtis (1993), students showed the growing journeys within the story on their maps.

We read No, I Want Daddy! by Nadine Brun-Cosme (2004) and changed the shape of the box on the response map to a heart to symbolically highlight emotional journeys. The response map for Stevie by John Steptoe (1987) showed two heads connected by a pathway to highlight the process of change within a mental journey. Each map was designed to push the young children to think more flexibly and symbolically about journeys.

The mapping responses were open-ended, providing space for children to explore their own interpretations and thinking about the books, but they were more focused than what we would typically have used within the lab, in that they directed children’s attention to particular themes within the book. In this case, the responses were designed to expand and develop students’ conceptualizations about journeys. After several experiences with maps, we opened up the mapping responses so that children could show their thinking on their own and asked them to choose two books to compare through creating a map that made sense to them. These responses showed evidence of the concepts that they were exploring:

The older students needed less support in moving to conceptual thinking about journeys. They were able to develop a mapping structure that fit their thinking and talk about their maps conceptually. We did not engage in these same mapping responses with them, but could move immediately to deeper conceptualization through text sets. They created maps to show their life journeys and to show their broad thinking about our touchstone text, The Pink Refrigerator, before moving to more in-depth considerations of journeys through text sets.

Developing Deep Conceptualization

After having multiple opportunities to think broadly about journeys, we spent time thinking in depth about issues related to journeys. The older students moved into this thinking earlier in work than did the younger children but all of the students gradually moved from engagements that encouraged them to broaden their conceptualizations of journeys toward more focused inquiry into conceptual issues around journeys.

Symbolic Thinking

Sketch to Stretch (Short, Harste, Burke, 1996) was one engagement we used to deepen students’ understanding through thinking symbolically. Sketch to Stretch is a graphic representation of the meaning of a text. The reader identifies an idea or concept he or she considers important from within a story, and then, using color, shapes, pictures, equations, or words communicates that understanding or connection symbolically.

Sketch to Stretch is challenging for children and often more so for adults, who frequently draw an illustration of the story rather than a connection to their thinking about that story. We found that it is helpful to show examples. I shared a Sketch to Stretch that I had created in response to a book that we had read in a previous session. I talked about how I thought about an important idea from within the story and then sketched images to represent the idea. I intentionally left my sketch unfinished and invited the students to suggest ideas that might make my sketch clearer. When they seemed to grasp that they could use color, shape, design, symbols, words or equations to represent the meanings of a text, I read a new story and asked everyone to show their thinking about the meaning of that story using Sketch to Stretch.

Changing the Scope of Thinking

We needed to recognize the big ideas within our thinking about a story and then consider the issues associated with those ideas in order to deepen our thinking. We started by working together to identify the big ideas in large group. After reading and talking about a book we asked children to identify the big ideas within the story and within their discussion of that story. Many of our older students and teachers had previously spent a great deal of time on identifying the main idea within stories and so we needed to open up their thinking to books exploring multiple big ideas.

The support of the large group in developing understanding seemed critical at this point. Individuals who were more confident spoke up, while those less sure were able to listen and learn from their peers. Within the large group, there were always a few who could identify at least one big idea within a story. We collected and discussed these examples, noticing that they were universal in the sense of carrying across many books and in students’ life experiences. From the examples and the talk around the examples, those who were initially less confident began to understand and identify big ideas themselves.

Complex thought is difficult to explain and almost impossible to explicitly teach. The group dynamics are powerful in helping learners to understand these nebulous ideas. Demonstrating and talking about the approximations made by some children provides pieces of meaning that we can all use to construct understanding. Over time, students and teachers were more comfortable identifying big ideas within the stories that we read.

The older students had several sessions where they browsed a large set of books that we had gathered around journeys. The books were not organized into any categories or themes so we asked students to work in small groups to web the big ideas that they found within these books. During study group, the teachers examined these webs across grade levels and identified some common reoccurring themes.

- Beginnings and Endings

- Dreams and Wishes

- Pain and Healing

- Spiritual and Emotional

- People and Relationships

- Growing and Learning

- Movement and Competition

We reorganized the books into text sets to encourage students to think in more depth about these themes or big ideas. Students selected a text set that was of most interest to them and spent several sessions in small groups reading and discussing the books around their theme. However, we wanted them to go beyond the idea or theme to the issues of most significance to them within that theme. We knew this shift in focus would be difficult for many.

We used a big idea that was represented across the webs from the different intermediate classes to demonstrate how to identify the issues around a big idea. Power was a big idea that many students identified in their reading. I wrote power in the center of a piece of chart paper and asked the kids to help me think about the issues that we encounter in our world related to power. I told them that when I think about issues in our world, I am often thinking about what is good, bad, fair and unfair about that idea. We all deal with issues related to power in our lives. Children have lived with and have strong feelings about the issues related to power as well. We webbed their responses about what they saw as good, bad, fair and unfair about power.

Students then went back to their text sets and chose one of the big ideas that they had identified from their text set. They discussed the idea and webbed the issues they saw as related to that idea.

Imaginative Thinking

Imagination is essential for students to be able to think critically about events and people outside their own experience. Empathy is a form of imagination. We require empathy to place ourselves within the story world in a real way, to see what the characters see, to know what they know, to feel what they feel. Otherwise, our tendency is to judge the characters’ experiences and ways of thinking based only on our perspectives of the world as the norm.

Toward the end of the semester we shifted as a group to look at forced journeys--journeys that people have no choice but to take. The older students looked at refugees, specifically people forced to flee their homes because of violence or natural disaster, while the younger students explored moving to a new town; a decision often made by parents without the input of children. Issues related to forced journeys had repeatedly emerged across different groups of students and we wanted to give students an opportunity to examine this issue in greater depth.

We engaged all the children in a simulation over the next few weeks. The older students were told that war was at their doorstep and they would need to flee within the next several weeks to a country that was willing to take refugees. Seven countries were willing to take a certain number of refugees and students could select only from those where there was space. The younger children were told that their parents had decided to move to New York City, clear across the country. We asked them to imagine what it would be like, how they would feel, what decisions they would make, and what they would need to do to prepare and adjust to their new homes if they were suddenly forced to move.

We used books to help students better understand these issues and to imagine ways of living beyond their own current lives. We gathered text sets about moving and picture books about refugees for read aloud discussions. We also had text sets for them to browse to help them explore the geography and cultures of their new homes and to help them imagine the differences and necessary adjustments to their lives and world views. Packing a suitcase or backpack for the journey forced them to further consider what was of most value to them in their current lives and in what ways their lives might change in another place.

Integrating Thinking through Synthesis

Synthesis is “a merging o f new information with existing knowledge to create an original idea, see a new perspective, or form a new line of thinking to achieve insight” (Harvey & Goudvis, 2000, p. 143). Intermediate students engaged in two experiences that required synthesis. While both were forms of assessment, it was clear that students continued to revise their understanding throughout these engagements.

After the intermediate students had a chance to think deeply about the issues explored within their journey text sets, we asked them to create a map or visual chart representing how the big ideas and issues each group had identified played out across the texts. We helped them envision this map by showing them a range of possibilities created by students from another school. In discussing the examples we told the students that their maps needed to communicate the important ideas and issues across the texts, they needed to have a title that communicated their focus to others, and that the structure of the map needed to fit the ideas they were trying to show.

As the students created their maps, the energy and depth of thought in each class was palpable. The maps became more that just a refection of what they already understood. The process of creating the map, deciding on a focus and a structure, selecting something worth communicating and collaborating in representing that idea pushed their understanding to new levels. What was exciting was seeing that students were aware that they were thinking in new ways. The process demanded synthesis.

The maps were an opportunity for group synthesis. At the end of our journey unit we asked the intermediate students to show their thinking in individual essays. Developing and supporting a thesis statement would require students to synthesize ideas that were most significant to each of them. We reviewed our learning by showing the students photographs of them during various engagements throughout the semester. We reminded them of the read alouds and posted their group charts and webs. Then we worked as a group to create a web of what each class felt they knew about journeys.

To push students to move to synthesis, I demonstrated how I might choose an idea to develop in an essay. I took a “wide angle” look at the web and asked myself, “What do I most want to say about journeys?” I shared an idea that occurred to me and demonstrated writing multiple thesis statements to address this idea.

Students were asked to engage in this same process of thinking. They were encouraged to write multiple thesis statements and share their thinking with others at their tables.

- When in a new place, you can have difficulties meeting people.

- Different people value different things.

- Journeys can be a new and learning experience.

- Moving causes a lot of changes making it usually hard or sad.

- Journeys cause you to leave things behind.

- Leaving people and things can be an emotional journey.

Once each student decided on a thesis statement, they individually wrote their essays. For all of the students this was a first experience writing an essay. Alex chose to explore the emotions that a refugee might face when forced to leave his home. He wrote:

When you do leave, it can leave you with mixed emotions. You may have left a lot behind but it was better for your safety. On the other hand, in the eyes of the refugee, what just happened was devastating. The journey ahead is just a guess. How long is it? How will you eat or drink? How will you get away?

German moved to our school from Mexico earlier in the year. His essay was an opportunity for him to share his personal experiences with adapting to a new home:

Friends here speak another language and they play different. Where I am from we do a lot of things in nature, such as fishing, walking and climbing trees. Here many kids play just sports and are much more competitive. This makes it hard for me to play with them.

Each student wrote about what was personally significant. As a result the essays were quite different than the reports that they were used to writing. They were interesting, original and personal and demonstrated remarkable understanding of the issues that we explored during our inquiry.

Conclusion

The thinking that learners can achieve is influenced by the experiences in which they engage, not through the type of questions to which teachers ask them to respond. If we continuously engage students in learning that requires complex thinking they will demonstrate and develop their existing thinking capacities within the school setting. Teachers also need to challenge their own thinking in order to recognize and support complex thought in their students. Analysis of student work further challenges teachers to identify different types of thinking in order to push themselves and their students to continue developing their thinking to new levels. As we continue to push for conceptual understanding in our students and ourselves we are amazed by the thinking that occurs. This thinking supports us in making sense of the important issues that we encounter in literature and that exist in our world.

References

- Brune-Cosme, N. (2004). No, I want daddy. New York: Clarion.

- Curtis, J. (1995). When I was little. New York: HarperCollins.

- de Deu Prats, J. (2005). Sebastian’s roller skates. La Jolla, CA: Kane/Miller.

- Egan, P. (2007). The pink refrigerator. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

- Erickson, H.L. (2002). Concept-based curriculum and instruction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

- Harvey, S. & Goudvis, A. (2000). Strategies that work. York, MA: Stenhouse.

- Short, K., Harste, J., Burke, C., (1996). Creating classrooms for authors and inquirers, Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Steptoe, J. (1987). Stevie. New York: HarperCollins.

- Waddell (1997). Once there were giants. New York: Candlewick.

WOW Stories, Volume I, Issue 2 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesi2.