Mapping Our Understandings of Literature

by Jaquetta Alexander, Second Grade Teacher, Van Horne Elementary School

Reading picture books aloud to my students has always been one of my favorite times of the day. Typically, these read-aloud times include talk about children’s personal connections and interpretations of a book. I have explored other ways of thinking and responding to books, such as sketches, drama, webbing, charting, and graffiti boards. These ways of responding provide time for students to reflect on their thinking about a story in ways that are often more supportive of young children’s thinking instead of only relying on talk to explore interpretations (Short, Kahn, & Kauffman, 2000). Recently I have been intrigued by the ways in which mapping has helped my students organize their thinking and explore relationships between ideas, people, and events in the stories we are reading.

I associate maps with geography and did not consider their potential as a response strategy until we began a conceptual exploration of journeys in the Learning Lab that carried over into my classroom. We used literature to challenge students to go beyond a literal understanding of journeys as trips to a more conceptual or metaphoric understandings. Each time we read a new book, students engaged in a literature discussion and some type of mapping response strategy. Given the connection of maps to journeys, mapping was a natural choice for response and for encouraging the development of conceptual thinking. This strategy gave the students a visual way to think about and organize their responses. By the end of the fall semester, students recognized that a journey could be much more than the physical movement from one place to another.

Moline (1995) argues that maps are used to place information in its spatial context. Maps can enable a learner to highlight spatial relationships, summarize a process, show changes over time, and record the movement of people or ideas. When children create maps, they are forced to organize their ideas and information on paper while paying attention to spatial relationships. They have to prioritize the ideas and information because they can’t include everything on the map. The spatial organization emphasizes the relative importance of particular ideas or events and provides a visual representation of the relationships between these ideas or events. For young children, the maps we created highlighted relationships and helped to make abstract concepts more concrete.

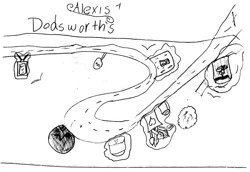

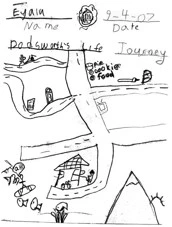

Our focus on journeys began with reading aloud The Pink Refrigerator by Tim Egan (2007). This became a touchstone text for our classroom because the students had a very strong connection to the book and continued to refer to it throughout the entire school year. Dodsworth owns a thrift shop, and each day visits the junkyard to bring back items to sell in his shop. One day he notices a pink refrigerator with a note attached, stating “make pictures,” and inside the refrigerator are paints, brushes, and a sketchbook. Dodsworth intends to sell the art supplies, but instead he uses them. Each day thereafter a new note appears and Dodsworth continues to carry out each exploration. Most students initially recognized this story as a physical journey of moving from one place to another in their maps of his life. Alexis drew a map reflecting her thinking that Dodsworth’s journey was basically linear, while Eyalu depicts Dodsworth's life journey as having pathways separate from his main route.

In our teacher study group, we reflected on the students’ understandings about journeys from this experience. It was apparent that they did not have a conceptual understanding and saw a journey as a physical movement from place to place. We decided to teach what they were on the edge of knowing about journeys—what they were starting to explore but didn’t quite grasp yet. That decision led us to focus on growing up journeys, emotional journeys, and learning journeys in our next experiences with the younger children.

Our next two books, Once There Were Giants by Martin Waddell and Penny Dale (1989) and When I Was Little by Jamie Lee Curtis (1993) presented stories about the changes young children go through as they mature. The students easily labeled this type of journey as a growing up journey. We asked students to create a simple map in which they identified and mapped some of the changes for the main character. We wanted them to explore journeys as changes that are not necessarily a physical change in location. Zach’s map of the little girl’s metamorphosis from When I Was Little is evidence of his understanding of the changes that occur on such a journey.

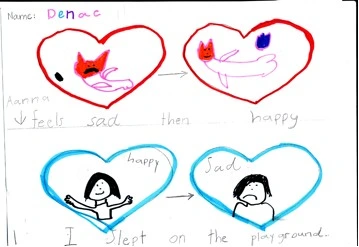

To challenge students to continue developing their conceptual understandings about journeys, we explored emotional journeys. No, I Want Daddy! By Nadine Brun-Cosme (2003) illustrates the many changes in emotion that a young girl experiences. Anna comes home happy, but her mother’s grumpy mood results in her anger and she decides she wants Daddy to do everything with her that evening. After her daddy tucks her in bed she feels as though something is missing until her mother quietly visits her. They are able to mend hurt feelings and Anna is finally able to sleep. We used the visual of a heart to help students map the emotional journeys that Anna goes through in the book. Students had to decide which of her emotional journeys they wanted to depict. Denae’s map reflects Anna’s change in feelings from sad to happy. On this map we also asked students to make a personal connection of a time when they experienced an emotional journey. Denae’s understanding is apparent in her illustration and her writing about her journey as well as Anna’s.

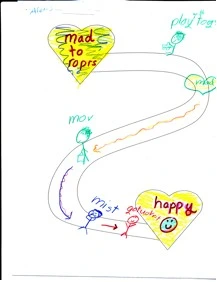

John Steptoe’s (1969) book, Stevie, deepened the students’ understandings of emotional journeys. Robert is angry that his mother is babysitting for another little boy. He is angry because Stevie plays with his toys when he’s at school and leaves dirty footprints on his bed. But when Stevie’s parents decide to move away, Robert is sad and misses him. At this point we recognized that students could see a change occurring in the different types of journeys so we decided to use the maps in a different way to highlight pathways. We wanted students to understand that there is a process that leads to change. Hearts were still used to illustrate the emotional aspect of the journey, but this time students selected an emotional change and illustrated the process of that change over time. Alexis chose to show Robert’s multiple changes in emotions across the book.

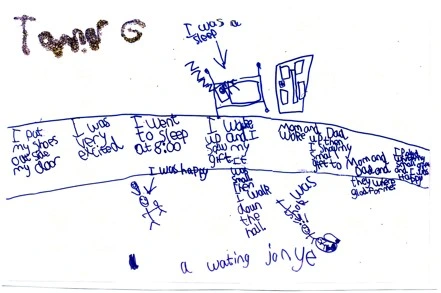

Another journey that students explored was a mind journey, which they also called a learning journey. Sebastian’s Roller Skates (de Deu Prats, 2003) was read aloud to further their conceptual understandings. The book tells a story of a shy young boy who gains confidence by learning to roller skate. As shown in Tanner’s map, Sebastian didn’t know how to skate at the beginning of the story, but learns to do so by the end of the story. This book was significant because not only did the students identify the learning journey, but they also understood that by learning to skate Sebastian gained confidence that helped him to overcome his shyness.

Initially I considered these mapping strategies as examples of students’ understandings about the books and about journeys. It wasn’t until several months after we began our exploration of journeys, that I realized the effect of thinking conceptually on my students as thinkers. We asked the students to look at all of their different maps and reflect with a partner. I realized this opportunity to analyze, make connections between maps, and explain each map to a partner was vital because when my students were asked, “What are some of the big ideas that are true about our world?” they showed a deep understanding of the concept of journeys. This question was posed to see if students could identify big ideas based on our explorations of journeys. I anticipated a retelling of events from the stories, but their responses were evidence that the students had a broad understanding of the concept:

- When you grow up you get to do different things.

- Growing up is like a journey because you start as a baby, then a kid, then a teenager, then an adult, then you’re old.

- When you grow up you have different things.

- You can learn from other people.

- You learn harder things as you get older.

- As you get older you get different kinds of emotions. When you’re younger you’re silly, when you’re older you’re serious.

- Sometimes your emotions change because of other people.

These responses show that the students were better able to see and understand the themes within each book and to form conceptual understandings of journeys at a metaphorical level. Erickson (2002) suggests that using a conceptual lens for a topic of study, as we did with journeys, facilitates and requires deep understanding and allows for the transfer of knowledge to new settings.

Additional evidence of their conceptual thinking occurred when the students voluntarily offered their own labels for journeys in books we were reading in the classroom. For example, one day while reading The Other Side by Jacqueline Woodson (2001), Manny commented that it included a “friendship journey.” In the spring when our concept study had shifted to human rights, my students were learning about how our choices affect our environment when Deana shouted out, “Wow, that’s a thoughtful journey because we have to always be thoughtful about our choices.” The students continued to recognize different types of journeys throughout the entire school year.

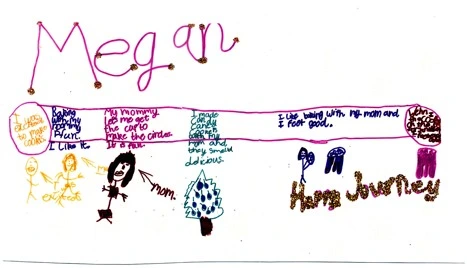

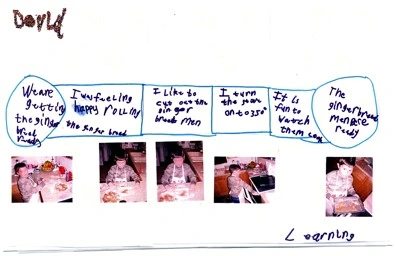

Our Holiday Memory Maps evolved from our involvement with the study of journeys. We asked the first and second-grade students to discuss their holiday traditions with their parents. Students were then asked to identify one of their favorite holiday memories and to map it using a pathway of their choice. After the map was created, the students labeled the kind of journey they experienced during that particular memory. Many students used familiar labels, such as emotional and learning journeys, and some created new labels. David’s learning journey, Megan’s happy journey, and Tanner’s waiting journey reflect some of the thinking that students engaged in around their memories.

A broad concept serves as an umbrella that students and teachers can use to encompass a wide range of topics, themes, and ideas. It does not limit the possibilities for class and student inquiries, but provides a point of connection across those inquiries (Short, et al., 1996). My students’ thinking grew from simple and concrete understandings that a journey represented physical movement from one place to another to the conceptual idea that a journey is a pathway of changes that involve growing up, emotions, and learning. Even more significant to me was the students’ ability to apply this conceptual knowledge in other areas, as they did with the Holiday Memory Map.

The mapping response strategies played a key role in supporting students in making this shift from literal to conceptual understandings and in applying their understandings in new contexts. Mapping provided a concrete way for them to visually show change over time through pathways and to understand the process of change. They could see the connections and relationships in ways that would have not been apparent if we had only used talk or writing to respond to the books. Mapping is a strategy that both extends and transforms students’ thinking and supports them in making the abstract concrete.

References

- Brun-Cosme, N. (2002). No, I want daddy! New York: Clarion.

- Curtis, J.L. (1993). When I was little. New York: HarperCollins.

- de Deu Prats, J. (2003). Sebastian’s roller skates. La Jolla, CA: Kane/Miller.

- Egan, T. (2007). The pink refrigerator. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Erickson, H. (2002). Concept-based curriculum and instruction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

- Moline, S. (1995). I see what you mean: Children at work with visual information. York, ME: Stenhouse.

- Short, K. G., Kauffman, G., & Kahn, L. (2000). “I just need to draw”: Responding to literature across multiple sign systems. The Reading Teacher, 54, 160-171.

- Short, K. Schroeder, J., Laird, J., Kauffman, G., Ferguson, M., & Crawford, K. (1996). Learning together through inquiry. York, ME: Stenhouse.

- Steptoe, J. (1969). Stevie. New York: HarperCollins.

- Waddell, M. (1989). Once there were giants. Ill. P. Dale. New York: Delacorte.

Woodson, J. (2001). On the other side. Ill. E.B. Lewis. New York: Putnam.

- Christian: It’s choices of where you’re going. Things you need to do. Life is a path. Choosing the wrong path can mean trouble for a while, and then you go back and fix it.

- Michael: Maybe going to other countries, trying new things, learning new things.

- Cole: Step by step. Just like in life.

- Ryan: Like a cartoon, picture by picture moving along on a road, pictures or visual images in our heads. It’s like watching a video.

- Sheshna: Step by step, everyday something different is going to happen. The past is going with you. Everything you do will stay with you.

- Cole: Life is a puzzle and you are the pieces.

- Sheshna: Everyday you are adding a piece of the puzzle. You are putting yourself together. Hey world, here I am!

- Michael: This is related to what Cole and Sheshna said. Sheshna said because we make the life journey, we might not remember everything. But we can remember by our journey maps. It may not seem important then, but later, it seems important.

- Christian: Life is a journey and an iceberg. It starts off small and builds as you go along. Sometimes bad things happen to it like the Titanic hitting it and causing it to be damaged. You never know what will happen in your life.

- Beginnings and Endings

- Dreams and Wishes

- Pain and Healing

- Spiritual and Emotional

- People and Relationships

- Growing and Learning

- Movement and Competition

- Connect

- Question/wonder

- Predict

- Determine importance

- Visualize

- Infer

- Synthesize

- Justina: Owen’s mother breathes fire to teach him a lesson. It’s a mental journey or maybe a spiritual journey from hurrying to relaxation? Mom goes from stressed out to relaxed. It’s mental because the mind had to slow down and relax.

- Andres: Pain is a journey. We had 5 books that were sad. I thought about death and how it changes your life. You’re going along one way and it makes you take a left turn. It’s a spiritual journey as well. If someone in your family dies, you will be sad. You go from happy to sad.

- Lisa: How is it a Spiritual Journey and not Emotional?

- Justina: A Mental category needs to be added. Emotional? Under Change, let’s add Death.

- Christian: I can back up Justina’s comment. I have lost someone. It changes your life right away. At first is a physical change, but after a while, it’s more spiritual. After 2-3 years you get used to the way it is. It’s really hard on the family. One person brings it up and everyone gets sad. Then it becomes…when you mention them once in a while. I didn’t read in Kinder and failed. I didn’t read because I did that with my dad and I didn’t want to share that with others. So I think Death should be added to the category of Mental Journeys. It connects from Emotional and then, Death.

- Things made of glass: Vase, light bulb, marble, and magnifier

- Things that were solid and not hollow: hammer, spoon, screwdriver, and plastic disk

- Things made of plastic: cup, spoon, pen, calculator, CD, basket, dice, thread spool

- Artistic/creative: brush, pen, paper, thread, game, dice, cards

- Hard or metal: (moved solid into this category)

- Stuff that made things work: battery makes toys work, key makes car work, calculator makes math.

- Hammer and screwdriver didn’t fit.

1. Sort all of the books into categories and label the categories with a sticky note.

2. Explain your categories to a teacher to make sure they make sense.

3. Record on the sheet how the books were sorted and the titles.

4. Start again by putting all the books in one pile and resort them into new categories.

Competition and Movement1st Sort: Sports, Practice, Relationships, and Conflict

2nd Sort: Power, Feelings, and Competition

3rd Sort: Children, Serious

4th Sort: Pain, Loving, Sharing/Not Sharing, Growing

Spiritual and Emotional1st: War/Conflict, culture, Trust, Metaphor/Symbols

2nd: Religion, Change, Family Culture, Death, and Elderly teaching

3rd: Cultural, Betrayal, Courage

4th: Family Trust, Anger, and Tragedy

Beginnings and Endings1st: Traveling, Cycles, Changes, Typical Day

2nd: Moving, Life, Ends where it Begins (circular)

Growing and Learning1st: Working, School Learning, Emotion, Adventures

2nd: Africa, Animals, Asia, USA

People and Relationships1st: Friendship, Relatives, And Not True Friends

2nd: Family, Trouble, Weekend, and Decisions

3rd: Not a Good Life, Caring, Funny, Helping, and Visiting

Dreams and Wishes1st: Animals, Funny, Countries, and Serious

2nd: Weird, Certain Time Period, Fantasy, Realistic Fiction, and Happy Endings

3rd: Magic, Your Own Thing, Far from Home, Trouble

Pain and Healing1st: Happy, Sad, Healing, Mad/Anger, Death

2nd: Pain/Tough Life, Racial, Jail/Caged, Meeting New People, Disabled

3rd: Different Country, Friendship

4th: War, Animals, Left Out, Different Life

- Justina: Power is something you want but don’t need. You have to go and get it. You have to push others to get it. Not with your hands, but if you want something, by demanding and telling them to give it to you.

- Ryan: Sometimes you have power and don’t know it.

- Christian: I think people need power. Look what’s happening in Iraq. Our president was power hungry. Other presidents wouldn’t have started was, but after 9-11.

- Ryan: We are there to free people not to control them. Hitler had bad power. Teachers have power. You can make us be quiet, tell us what to do, and leave when you want. If we don’t listen, it takes away power. Because you have power, you are responsible.

- Maya: Gender is an issue. Girls don’t have as much power.

- Michael: People who are famous have power. They can tell us what to do.

- Maya: Popularity. Some girls say you have to do what I say. They think they have power. We have power if we have determination to get power.

- Justina: The president has power. He can make people do anything.

- Lisa: How does he get power?

- Michael: Everyone can get power if they try. There are many ways to get power but sometimes it doesn’t always work.

Text Set:

Beginnings and Endings

(Marshall, Queta, Kaleb, Shawn)

Big Idea: Adventure

This group used a game board format because it represented an adventure. Adventures provide learning experiences.

Marshall: It is important to kids so they can share what they learn through life.

Text Set:

Dreams and Wishes

(Justina, Alex, Kynshyla, and Maya)

Big Idea: Hard work pays off.

This group used puzzle pieces to show connections between the texts and stars to show what was magic in each book.

Kynshyla: You had to work your way through stuff. Nothing is given to you. Work to earn your reward.

Justina: Be patient. It (the reward) is not always going to come to you right away.

Kynshyla: You don’t always get what you work for, but you get something in return.

Alex: You have to work but then wait for the reward.

Text Set:

Pain and Healing

(Ryan, DG, Nicolas, and Andres)

Big Idea: Andres: Pain causes or leads to healing.

DG: We noticed that it was connected in some way.

Text Set:

Spiritual and Emotion

(Christian, Austin, and Cole)

Big Idea: Change Ex. Family, Separation, Death, Moving, Cause of War all had something to do with change.

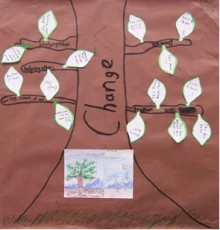

This group used a creative way to display the information on a tree where the branches were the big ideas and the books were the leaves on each branch. The most significant thing for this group was the concept of “Changing of things through Life. Spiritual/Emotional changes can affect our inner selves. Change can help and hurt us.”

Image

Text Set:

People and Relationships

(Maycee, Mary, Sarena C., Serina T.)

Big Idea: Family relationships.

How families make their decisions, connected to books and how they care for each other.

Text Set:

Growing and Learning

(Madison, Sheshna, Susana)

Big Idea: Challenges

Challenges can be good and bad. Something you don’t want to do but have to. You can learn from it or challenges can push you backwards.

Text Set:

Movement and Competition

(Michael, Joey, Angel, Jordan)

Big Idea: Competition

The way people treat each other during competition. The use of insults, not true statements, intimidation. Treating each other as if one was better than the other. It matters how they treat each other.

Image

- Beaugrande, R. (1980). Text, discourse, and process. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

- Erickson, H.L. (2002). Concept-based curriculum and instruction: Teaching beyond the facts. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

- Pink, D. (2005). A whole new mind: Why right-brainers will rule the future. New York: Berkley.

- Santman, D. (2005). Shades of meaning. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Short, K.G. (1993). Making connections across literature and life. In Holland, K., Hungerford, R. & Ernst, S. eds. Journeying: Children responding to literature. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Short, K.G. & Harste, J. (1996). Creating classrooms for authors and inquirers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Bartoletti, S. (2005) Hitler youth. New York: Scholastic.

- Bunting, E. (1991). Fly away home. New York: Clarion.

- Diakite, P. (2006). I lost my tooth in Africa. New York: Scholastic.

- Egan, T. (2007). The pink refrigerator. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

- Garland, S. (1993). The lotus seed. San Diego: Harcourt Brace.

- Lauture, D. (1996). Running the road to ABC. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Leonard, M. (2002). Tibili. La Jolla, CA: Kane/Miller Book Publishers.

- Lionni, L. (1960). Inch by inch. New York: Harper.

- Lowry, L. (1989). Number the stars. New York: Yearling.

- Propp, B. (1999). When the soldiers were gone. New York: Putnam.

- Sciesza, J. (1995). Math curse. New York: Viking.

- Sherpa, A.Z. (1997). Zangbu’s Story. Seattle: Storytellers Ink.

- Shin, S.U. (2004). Cooper’s lesson. San Francisco: Children’s Book Press.

- Teckenrup, B. (2007). How big is the world? New York: Boxer.

- Waddell, M. (1989). Once there were giants. New York: Delacorte.

- Yolen, J. (1988). The devil’s arithmetic. New York: Viking.

- D’Adamo, F. (2001). Iqbal. New York: Aladdin.

- Morrison, T. (2002). The big box. New York: Hyperion/Jump at the Sun.

- Perez, L.K. (2002). First day in grapes. New York: Lee & Low.

- Pin, I. (2006). When I grow up, I will win the Nobel Peace Prize. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

- Ryan, P.M. (2000). Esperanza rising. New York: Scholastic.

- Short, K., Harste, J. & Burke, B. (1996). Creating classrooms for authors and inquirers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Whitin, P. (1994). Opening potential: Visual response to literature. Language Arts, 71, 101-107.

- Wiles, D. (2001). Freedom summer. New York: Atheneum.

• Journeys can be hard.

• Sometimes you have to leave things that are important behind.

• Journeys can take you to an unexpected place→ good or bad (you don’t always get to where you wanted to go).

• Journeys can be easy.

• You face challenges in journeys.

• Things that are important to you change along the way (one of the hard parts of being a refugee).

• Find out their lifestyle.

• Get more money.

• Learn a new language.

• Find a new school - Make new friends as school.

• Leave things behind.

- Sarvnaz: You need to be brave and smart when you go to a new place.

- Aden: Physical journeys can be challenging.

- Thomas: Journeys can change peoples’ lives.

- Conner: If you are a refugee you will have to leave some of your most important things behind.

- Applegate, K. (2007). Home of the brave. Minneapolis, MN: Fiewel & Friends.

- Bunting, E. (2005). Gleam and glow. Ill. P. Sylvada. New York: Voyager.

- Egan, T. (2007). The pink refrigerator. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Harvey, S. & Goudvis, A. (2000). Strategies that work. York, ME: Stenhouse.

- Keene, E. & Zimmermann, S. (1997). Mosaic of thought. Portsmouth, NH: Heinmann.

- Lofthouse, L. (2007). Ziba came on a boat. Ill. R. Ingpen. La Jolla, CA: Kane/Miller.

- Ryan, P.M. (2002). Esperanza rising. New York: Scholastic.

- Feelings, T. (1995). The middle passage. New York: Dial.

- Paterson, K. (1996). Jip. New York: Scholastic.

- Rappaport, D. (1991). Escape from slavery: Five journeys to freedom. New York: Harper.

- Ruby, L. (1994). Steal away home. New York: Aladdin.

- Short, K., & Harste, J. with Burke, C. (1996). Creating classrooms for authors and inquirers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Short, K., Kauffman, G., & Kahn, L. (2000). “I just need to draw”: Responding to literature across multiple sign systems. The Reading Teacher, 54(2), 160-171.

- Wilson, G.P. (2003) Supporting young children’s thinking through tableau. Language Arts, 80(1), 375-383.

- Yates, E. (1950). Amos Fortune, free man. New York: Dutton.

Owl Moon

(Yolen,1987)

When I was Young in the Mountains (Rylant, 1982)

Christmas in the Country (Rylant, 2005)

Going Home (Bunting, 1998)

Mim’s Christmas Jam (Pinkney, 2001)

Christmas Tree Memories (Aliki, 1994)

The Wednesday Surprise (Bunting, 1989)

My Mama Had a Dancing Heart (Gray, 1999)

Just the Two of Us (Smith, 2005)

Chanukah Lights Everywhere (Rosen, 2001)

The Trees of Dancing Goats (Polacco, 1996)

• It was about her memories.

• The author was in the story.

• It was about having family together.

• I wonder if she still lives in the mountains.

• It reminds me of when my brother was a little boy because she was little.

• I felt bad for her she didn’t have a bath and stuff.

• It makes me feel cold.

• I reminded me of Christmas. She was scared and so was I when I went to the mountains.

• I got it I can see what they all have.

• They all have family and love.

• No they all have memories.

• All the books go together.

- Aliki. (1994). Christmas tree memories. New York: Harper-Trophy.

- Bunting, E. (1998). Going home. Ill. D. Diaz. New York: Harper Trophy.

- Bunting, E. (1989) The Wednesday surprise. Ill. D. Carrick. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Gray, L. (1999). My mama had a dancing heart. Ill. R. Colon. New York: Orchard.

- Pinkney, A. (2001). Mim’s Christmas jam. Ill. B. Pinkney. New York: Gulliver.

- Polacco, P. (1996). The trees of dancing goats. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Rosen, M. (2001). Chanukah lights everywhere. New York: Gulliver.

- Rylant, C. (1982). When I was young in the mountains. Ill. D. Goode. New York: Dutton.

- Rylant, C. (2005). Christmas in the country. Ill. D. Goode. New York: Scholastic.

- Short, K.G & Harste, J. (1996). Creating classrooms for authors and inquirers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Short, K.G. (1993). Making connections across literature and life. In Holland, K., Hungerford, R & Ernst, S., eds. Journeys among children: Responding to literature. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Smith, W. (2005). Just the two of us. Ill. K. Nelson. New York: Scholastic.

- Yolen, J. (2002). Owl moon. Ill. J. Schoenherr. New York: Philomel.

What types of journeys are occurring?

What makes it a journey?

Nick:

You go through challenges that are hard.

James: In life things are sometimes hard and sometimes not.

Brittney: You are getting through easy, fun, and hard stuff.

Kaitlynn: Obstacles are bumps in your journey. Challenges are like a bump. Challenges are like when you turn too fast.

Elana: There are lots of events in both.

• wanting to do new things

• doing new things

• physical journeys (Dodsworth going to the ocean and going to the junk yard everyday)

• life journeys

• maturity journeys

• following interests

• time journeys

• history journeys

• friendship journeys

• pet journeys (getting used to a new pet)

• sports journeys

• medical journeys (surgeries)

• growing up (birthdays)

• first-time journeys (first day of school)

• adventurous journeys

• school journeys (field trips)

• moving journeys

• Animals working together:

No, I Want Daddy!

,

Koala Lou

,

Anansi

,

Fox• People working together: Baseball Saved Us, Stevie

• Things that make the characters try new things: The Pink Refrigerator, Sebastian’s Roller Skates

• Changes because of getting older: Once There Were Giants, Wilford Gordon MacDonald Partridge

• Problems with mothers:

Koala Lu

,

No, I Want Daddy!• Being trapped: Anansi, Fox

• Going to School: Once There Were Giants, Sebastian’s Roller Skates

• Pushing someone away: Fox, No, I Want Daddy!, Baseball Saved Us

• Sitting around: Wilford Gordon MacDonald Partridge, The Pink Refrigerator

• Physical Journey:

The Pink Refrigerator

,

Sebastian’s Roller Skates

,

Anansi

(The students then realized that all the books could fit in this category)

• Growing Journey: Once There Were Giants

• Mental Growth Journey: Wilford Gordon MacDonald Partridge

• Learning Journey: Baseball Saved Us, The Pink Refrigerator, Sebastian’s Roller Skates, Koala Lou

• Emotional Journey: Koala Lou, Stevie, No, I Want Daddy!, Fox

• working together

• things that make you try new things

• change because of getting older

• being trapped

• pushing someone away

• problem with mothers

• sad about being alone

• going to school

• sitting around

• life experiences

• growing journeys

• mental growth journey

• emotional journey

• going journey (physical journey)

• learning journey

- Brun-Cosme, N. (2002). No, I want daddy! New York: Clarion.

- Calkins, L. (1995). The art of teaching writing. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- de Deu Prats, J. (2003). Sebastian’s roller skates. La Jolla, CA: Kane/Miller.

- Egan, T. (2007). The pink refrigerator. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Erickson, H.L. (2002). Concept-based curriculum and instruction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

- Fox, M. (1988). Koala Lou. Ill. P. Lofts. New York: Voyager.

- Fox, M. (1985). Wilford Gordon MacDonald Partridge. Ill. J. Vivas. LaJolla, CA: Kane/Miller.

- McDermott, G. (1972). Anansi the spider: A tale from the Ashanti. New York: Henry Holt.

- Mochizuki, K. (1993). Baseball saved us. New York: Lee & Low.

- Short, K.G. (1993). Making connections across literature and life. In Holland, K., Hungerford, R., & Ernst, S. (eds.). Journeys among children: Responding to literature. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Steptoe, J. (1969). Stevie. New York: HarperCollins.

- Waddell, M. (1989). Once there were giants. Ill. P. Dale. New York: Delacorte Press.

- Wilde, M. (2000). Fox. Ill. R. Brooks. La Jolla, CA: Kane/Miller.

- Applegate, K. (2007). Home of the brave. New York: Feiwel & Friends.

- Avi. (1984). The fighting ground. New York: Harper Trophy.

- Budhos, M. (2006). Ask me no questions. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Bunting, E. (2001). Gleam and glow. Ill. P. Sylvada. Orlando, FL: Harcourt.

- Collier, J.L. & Collier, C. (1974). My brother Sam is dead. New York: Scholastic.

- D’Adamo, F. (2003). Iqbal. New York: Aladdin.

- Feeling, T. (1995). The middle passage: White ships/black cargo. New York: Dial.

- Hathorn, L. (1994). Way home. New York: Crown.

- Lewison, M., Flint, A.S., & Van Sluys, K. (2002). Taking on critical literacy: The journey of newcomers and novices. Language Arts, 79(5) 382-392.

- Lofthouse, L. (2007). Ziba came on a boat. Ill. R. Ingpen. La Jolla, CA: Kane/Miller.

- Mc Govern, A. (1997). The lady in the box. Ill. M. Backer. New York.

- O’Dell, S. (1980). Sarah Bishop. New York: Scholastic.

- Pradl, G. (1996). Literature for democracy: Reading as a social act. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook

- Rosenblatt, L. (1938). Literature as exploration. Chicago: Modern Language Association.

- Shea, P. (2003). The carpet boy’s gift. Gardiner, ME: Tilbury House.

- Sherpa, A.Z. (1997). Zangbu’s Story. Seattle: Storytellers Ink.

- Walsh, J. (1982). The green book. New York: Sunburst.

- Wilson, G. P. (2003). Supporting young children’s thinking through tableau. Language Arts, 80(5) 375-383.

- Woodruff, E. (1991). George Washington’s socks. New York: Scholastic.

• David said that he didn’t care about the woman, and that he just wanted to keep his career.

• Adrian stated that he didn’t want to lose customers.

• Jason argued with the deli owner that Dorrie was freezing and needed food.

• Denae said that Dorrie needed a warm place to stay.

• Eyalu stated that Dorrie needed to stay at the shop because she needed the warm air.

• Tanner said that she’ll maybe die because the other places are too cold.

Megan:

I wonder if we have a rule like that.

Jake: People would be nicer if we had one.

Tanner: We would have no war if all countries had it.

Denae: I wonder what it’s about, about being nice or is it your imagination?

Jacob: It’s hard to live by.

Megan: It’s a part of being nice to people.

Manny: I wonder what our moms and dads would say about it?

Jake: We should have a golden rule at our homes.

Ben: I wonder if cavemen did it.

David: Some people don’t care about other people and then it turns into a big mess.

Jake: Some people don’t remember it because it’s so old.

Zach: I don’t think people forgot. I think they don’t know about it.

Tanner and Deana agreed: Some people don’t care and don’t follow it.

Tanner: If the golden rule was the law, the world would be really different.

• To have lunch

• To pick up trash

• To be treated with respect

• To have a principal

• To have a teacher

• To get a turn when playing a game

• Nobody disturbs anybody when they’re reading a book

• To have a break for eating

• To play a game

• To listen to the teacher without other people distracting us

• To come to a clean school

• To not ignore the teacher

• To not be bullied

•

Longer time outsideStudents need to get out their wiggles

Teachers have time to finish work

• Clean school

Makes our school healthier

Keeps clothes from getting dirty

Helps to recycle and the world benefits

Helps Mr. Leo (our custodian)

Good for animals

Easier for monitors because they always ask kids to clean up

• Have more parking spaces

Less accidents

More people can come to school

- Have you ever seen trash blowing over from the dump? Tell us about it.

- Do you think the dump people can do something? Tell us about it.

- Is there anything we can do to stop the dump from letting the trash blow into our school? Tell us about it.

- Is there a way we can move the dump from Van Horne? Tell us about it.

Is the trash really from the dump? Tell us about it.

Jason: It means that you do it.

Tanner: It’s standing up for yourself or others.

Jacob: Some people take action by trying to solve a problem.

Zach: You can take action by doing something bad or good.

Manny: You can take action for anything – something you care about.

Adrian: Sometimes when you take action it affects other people.

David: Sometimes when you take action it might help/ change the world.

Jason: You can take action by picking up trash.

Deana: And by reminding others to pick up trash.

Manny: You have to take time to think about your action and how it might cause things to happen.

Jacob: Sometimes when you try to think of an action you can be mean or nice.

Jason: You can take action by helping people.

Manny: Don’t raise your voice while you’re trying to take action.

Jacob: Sometimes when you take action you need help.

Megan: One way of taking action is to be nice.

Tanner: You can take action anywhere. It doesn’t have to be just at school or home.

Megan: You can take action by not bullying.

Manny: When you take action you have to really figure out what’s wrong.

Denae: You can take action by helping people.

Jacob: I’ve recognized sometimes that bullying is trying to solve a problem meanly.

David: Maybe we could help everyone.- Atkins, J. (1995). Aani and the tree huggers. New York: Lee & Low.

- Bunting, E. (1993). Someday a tree. New York: Clarion.

- Cooper, I. (2007). The golden rule. New York: Abrams.

- Creech, S. (2001). A fine, fine school. New York: HarperCollins.

- Edmiston, B. (1993). Going up the beanstalk: Discovering giant possibilities for responding to literature through drama. In Holland, K., Hungerford, R. & Ernst, S., eds. Journeys among children responding to literature. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Gifford, P. (2007). Moxy Maxwell does not love Stuart Little. New York: Schwartz & Wade.

- Gifford, P. (2008). Moxy Maxwell does not love writing thank-you notes. New York: Schwartz & Wade.

- Hart, R.A. (1992). Children’s participation: From tokenism to citizenship. Florence, Italy: UNICEF.

- Lyons, D. (2002). The tree. New York: Scholastic.

- McGovern, A. (1997). The lady in the box. New York: Turtle.

- Short, K. & Harste, J. (1996). Creating classrooms for authors and inquirers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Van Allsburg, C. (1990). Just a dream. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Vasquez, V. (2004). Negotiating critical literacies with young children. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Everyone has the right to play games on the playground or in the classroom.

- Everyone has the right to learn.

- Everyone has the right to have a friend.

- Everyone has the right to eat lunch for their energy.

- Will she read Stuart Little?

- The book is ruined.

- She will keep herself busy so she doesn’t have to read the book.

- She will run out of time.

- Moxy is still a daydreamer.

- Moxy doesn’t want to or like to write thank you notes.

- Consequences are a part of this book as well.

- Moxy has a choice to write the letters.

- Moxy has bad ideas.

- Moxy tries everything to not do what she’s supposed to.

- In both books she had a great idea that turned bad.

- Gifford, P. (2007). Moxy Maxwell does not love Stuart Little. New York: Schwartz & Wade.

- Gifford, P. (2008). Moxy Maxwell does not love writing thank-you notes. New York: Schwartz & Wade.

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. New York: Macmillan.

- Haley: To get what you want you have to take peaceful action.

- Tanner: All the books had people who cared about the earth.

- Jacob: All books had people who were nice.

- Eyalu: All the books are about the earth and that it’s important to take care of it.

- The big idea from The Tree was to save what you love.

- The big idea from Just A Dream was to take care of the earth.

- The big ideas from Aani and the Tree Huggers were taking action, bravery, and courage.

- The big ideas from Someday a Tree were hope and friendship.

- Some of the choices people made in the books to make the world a better place were replanting the tree, giving the tree new soil, picking up trash, not cutting the tree down, and making a circle around the tree.

- Atkins, J. (1995). Aani and the tree huggers. New York: Lee & Low.

- Bunting, E. (1993). Someday a tree. New York: Clarion.

- Crawford, K., Ferguson, M., Kauffman, G., Laird, J., Schroeder, J., & Short, K. G. (1998). Examining children’s historical and multicultural understandings: The dialectical nature of collaborative research. In T. Shanahan & F. Rodriquez-Brown, National Reading Conference Yearbook, 47, 323-333.

- Lyons, D. (2002). The tree. New York: Scholastic.

- Van Allsburg, C. (1990). Just a dream. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Kaye, C.B. (2004). The complete guide to service learning. Minneapolis: Free Spirit.

- Lofthouse, L. (2007). Ziba came on a boat. Ill. R. Ingpen. La Jolla, CA: Kane/Miller.

- Rosenblatt, L.M. (1995). Literature as exploration. New York: The Modern Language Association.

- Williams, K.L. & Mohammed, K. (2007). Four feet, two sandals. Ill. D. Chayka. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

- Williams, M. (2005). Brothers in hope. Ill. G. Christie. New York: Lee & Low.

- Anzaldua, G. (1993). Friends from the other side. San Francisco: Children’s Book Press.

- D’Adamo, F. (2005). Iqbal. New York: Aladdin.

- McGovern, A. (1997). The lady in the box. New York: Turtle.

- UNICEF (2001). For every child. New York: Dial.

- Rosenblatt, L. (1938). Literature as exploration. Chicago: Modern Language Association.

- Shea, P.D. (2003). The carpet boy’s gift. Gardiner, ME: Tilbury House.

- Wade, R.C. (2007). Social studies for social injustice. New York: Teachers College.

WOW Stories, Volume I, Issue 2 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesi2.