Taking Action with Young Children

by Jaquetta Alexander, Second Grade Teacher, Van Horne Elementary School

Adults often think that taking action is beyond kids. This assumption has been challenged by Vivian Vasquez (2004) whose research shows that young children can use their intelligence and voices to create change in their world on issues that are significant in their lives. My own experiences with young students indicates that they are capable of understanding broad concepts, such as human rights, and taking action in ways that make sense to them. The teachers in our school decided to focus our work in the Learning Lab on human rights during the spring semester. Because I teach second grade, we decided to begin with exploring fair and unfair because this concept was already familiar to children and something they frequently commented on. We introduced the concept of human rights at a global level after students had the opportunity to map and label events they considered fair or unfair at school. Our goal was to encourage students to identify an issue on which they wanted to take action with authentic intentions. We wanted the action to grow out of their concerns and problem-posing, not manipulate them to act on our intentions as adults (Hart, 1992).

I worked collaboratively with Jennifer Griffith, a first grade teacher, to structure time outside of the Learning Lab in our classrooms to enhance the thinking that was evolving from our work in the lab. Our work in the Learning Lab and in the classroom combined to create a foundation of understanding that was quite evident when my students were asked to reflect on their understandings about what it means to take action at the end of the school year. Their explorations of human rights and taking action were supported by our use of the same structure of read aloud, literature discussion, and response strategy in the lab and the classroom. This routine allowed students to become comfortable in knowing what was occurring next and in taking risks to explore their thinking and ideas. Our focus as teachers was on thinking with students but also on challenging them to push their thinking. After each reading, students participated in a literature discussion that not only allowed them to hear and respond to other students’ thinking but also gave them the opportunity to consider new ideas.

As I read through my field notes and looked at student work, I realized that there were a number of key interactions that supported these young children in building their understandings of human rights and being able to move toward taking action. Some of these events occurred within the lab and others in the classroom, but they all revolved around children exploring multiple perspectives and considering “big ideas.”

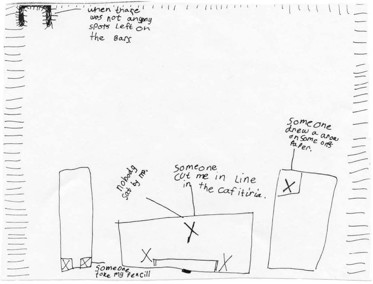

We began our human rights inquiry by reading A Fine, Fine School by Sharon Creech (2001). Following our literature discussion, students created a map of the school and identified places where unfair things had occurred, either to them or another student. As the inquiry continued, students were offered many opportunities to engage in the wide reading of books on human rights, both in schools and in the world more broadly. These readings helped students make connections to their own lives and to conceptualize and think about the big picture. Short and Harste (1996) argue that inquiry should always begin with connections to the concept based on children’s life experiences as a base from which to broaden their understandings. Deana’s map, for example, shows times where she or someone else was treated unfairly–someone cut her in line or drew an arrow on another person’s paper, etc. Deana did not use names on her map, because we had carefully discussed that the maps were not about tattling.

Early in our inquiry, students had a difficult time understanding the concept of rights. For example, a student would respond to the question, “What is your right?” by stating, “To treat people fairly” instead of “To be treated fairly.” Near the end of the semester we saw a shift in student thinking, and they were able to verbalize more clearly their thoughts on human rights. We revisited the students’ maps of the school because these maps had introduced them to the concept of human rights and they were able to look at the unfair events and think about the rights these represented.

A key interaction occurred when students considered different perspectives on human rights. We were exploring the power that we have to make choices to create a better world. After reading The Lady in the Box by Ann McGovern (1997), my students used drama to view the world through someone else’s perspective. The text was about a homeless woman, Dorrie, who lives in a box in front of a local deli. The warm air that comes through the grate from the basement of the deli keeps her warm in the harsh winter weather. Two young children, Lizzie and Ben, live nearby and leave her food and warm clothes. When the deli owner forces Dorrie to move her box away to a much colder location, the children ask their mother for help. She confronts the deli owner and convinces him to let the Dorrie stay.

We engaged students in a drama where they worked in pairs–within each pair one student played the role of the deli owner while the other took the role of one of the children. Edmiston (1993) argues that, “Drama enables students to respond thoughtfully and insightfully to literature” (p. 250). This thoughtfulness was evident in my students’ responses. Students playing the role of the deli owner took on different perspectives:

Students who played the role of either Lizzie or Ben also expressed a range of perspectives:

We did not use drama to act out the plot of the story, but to extend the students’ thinking about the plot, the relationships between the characters, and the issues of homelessness and taking action. Their responses indicate they were thinking conceptually about human rights.

Another key interaction occurred around The Golden Rule by Ilene Cooper (2007), in which a boy and his grandfather discuss different cultural variations of the rule that we should treat others as we ourselves want to be treated. The ending of the book was especially critical because the boy and his grandfather use their imaginations to think about how the boy can act on the Golden Rule in his life. The students easily made connections because these examples were about new students and bullying, both of which they had experienced. The big idea statements in the book about the cultural variations of the Golden Rule pushed students’ understandings because these statements articulated the issues they had been exploring, but at a much higher conceptual level. Students also began considering choices and how they affect other people.

Because the text integrated the perspectives of many cultures and highlighted the power of choice, this read-aloud was a pivotal moment in connecting our previous experiences with our focus on moving toward action. Comments in the literature discussion included:

This book influenced student thinking by supporting them in synthesizing their previous discussions and experiences through exploring the broad thematic statements in the book about the Golden Rule. This book pushed students to begin thinking about making choices to make the world a better place, which provided a link to our classroom inquiries.

Jennifer Griffith, a first grade teacher, and I extended the lab work into our classrooms through two experiences that were significant in continuing to build our students’ conceptual understandings of human rights. The first, our read aloud of Moxy Maxwell Does Not Love Stuart Little (2007) and Moxy Maxwell Does Not Love to Write Thank You Notes (2008) by Peggy Gifford helped the students see the value of making choices and to consider how those choices affect others and sometimes the world.

By charting the big ideas of these chapter books after each read aloud, we were able to see the shift in student thinking and understanding, especially from the first book to the second. During the first book students recognized several big ideas, such as Moxy keeping herself busy so she wouldn’t have to read the book, Moxy as a troublemaker who was bossy, Moxy not caring about the book, and Moxy looking closely at the cover to develop a true interest in the book. During the second book the students not only recognized that Moxy was making choices, but their responses reflected more complex thinking about the influence of her choices on herself and others. They talked about Moxy still being a daydreamer, the consequences of her actions, Moxy having a choice to write the thank-you letters, the influence of teamwork and helping others, Moxy not having a choice to write the notes, Moxy as someone who tries to get attention, Moxy having bad ideas that led to poor choices, Moxy telling the truth, and choices for the greater good of others. The two books were crucial in helping the students comprehend the power and consequences of choice.

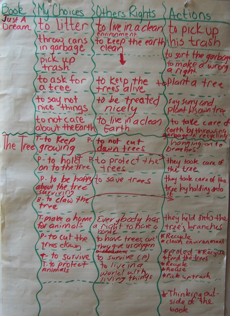

The second key interaction was our study of the environment. We connected the study to Earth Day and focused on the choices that characters were making in picture books we read aloud about the environment. Four books were especially significant for student understanding: Aani and the Tree Huggers by Jeannine Atkins (1995), Someday a Tree by Eve Bunting (1993), Just A Dream by Chris Van Allsburg (1990), and The Tree by Dana Lyons (2002). Ultimately, our goal was to have students explore how our choices affect others. Jennifer and I brainstormed different strategies that we hoped would enable our young students to see this connection. The following chart played a key role in organizing students’ thinking. On the chart, we recorded student thinking about each book for a particular set of categories. The students identified the choices made by characters within the book, whether they were viewed as positive or negative choices, the right that each choice influenced, and the action that was taken in connection to those choices and rights.

These two inquiries around the Moxy Maxwell books and environmental picture books created a context through which the students could conceptualize human rights and consider ways of taking action to create a better world. Roger Hart (1992) argues that, “Children need to be involved in meaningful projects with adults. It is unrealistic to expect them suddenly to become responsible, participating adult citizens at the age of 16, 18, or 21 without prior exposure to the skills and responsibilities involved” (p. 5). Hart argues that children’s participation in taking action needs to move from tokenism to active involvement so that students’ voices are integral to the actions that are being discussed.

We began and ended our inquiry on human rights by asking students about problems that they recognized at our school. We charted their ideas and revisited them often. As adults, our role was to create a framework that students could use to think about taking action in the context of human rights, and to help them understand that a right is not the same as a wish. Within this framework, the problems and solutions that were generated grew out of student thinking. We did not impose our thinking onto students but thought with them and provided structures that would challenge them to think more deeply about their understandings of rights and taking action and to consider perspectives beyond their own.

Midway through the inquiry students were asked, “What are the rights of students at Van Horne?” Their responses were varied:

These responses indicate that some students were still struggling with understanding human rights and with distinguishing between a right and a wish. Later in the study the students added the following comments about their rights at school and their justification for this right:

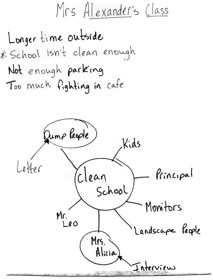

Eventually we asked students to narrow down the possible rights to make a decision of one that they wanted to immediately take action on. After much deliberation and brainstorming the students decided that they wanted to make our school a cleaner place. They were particularly concerned because they believed that most of the trash was blowing onto the playground from a nearby landfill and thought that a letter of complaint should be written to the “dump people.” We talked about the need to get other perspectives on this issue and brainstormed a list of who they thought would have important perspectives:

To see the problem from a perspective other than their own, the students decided to interview Mrs. Alicia, one of our custodians. They developed the following five questions:

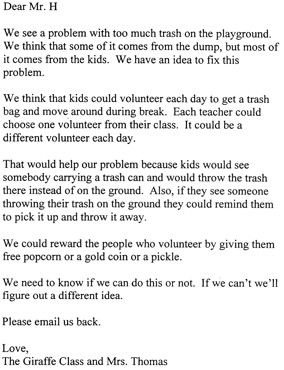

After hearing Mrs. Alicia’s responses the students decided that the dump was not the primary problem of the trash on our school grounds—they were. They realized that students were producing the trash that was most problematic but also decided that the biggest problem was the lack of containers for trash available on the playground. After much discussion, they took action by writing a letter to our principal that shows how they decided they wanted to resolve the problem.

The most rewarding part of the process for me was watching the students’ thinking evolve from a primary level of understanding to a complex, conceptual understanding of human rights. The most powerful evidence of their shift in thinking was apparent when students were asked, “What can you tell us about taking action?” on the last week of school. We wanted to see how they defined taking action. Their responses included:

Students also did a sketch to stretch (Short & Harste, 1996) to show their thinking about the meaning of taking action. They had to use visual images to symbolize their understandings.

The students’ visual and verbal responses indicate the growth in their ability to think critically about broad concepts such as human rights and taking action. Early in our inquiry, I was frustrated by their willingness to passively allow adults to make decisions for them. They didn’t believe that taking action was an option for them as young children and didn’t view themselves as being able to make decisions—that was what the adults in their lives did. Our literature discussions and charts supported them in recognizing that they are continuously making choices on a daily basis that affect their lives. The drama and interview challenged them to realize that those decisions should involve considering a range of perspectives, not just acting on their own views. These understandings provided the basis for students to start developing a strong sense of their own agency and empowerment in making decisions, not just to benefit themselves, but to benefit the world. This process also supported my own sense of agency as a teacher in making decisions in the classroom to both support and challenge the conceptual thinking of young children. The power to make choices to create a better world describes our work within classrooms as teachers and students as well as our life work as human beings.

References

WOW Stories, Volume I, Issue 2 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesi2/.

One thought on “WOW Stories: Connections from the Classroom”