Affirming Cultural Identity and Diversity through Children’s Literature

Teresa Johnston

I have a passion for children’s literature which grew from listening to my mother read stories to me. These words penned by Strickland Gillilan (1936) in his poem “The Reading Mother” apply to my childhood experience:

You may have tangible wealth untold;

Caskets of jewels and coffers of gold.

Richer than I you can never be —

I had a Mother who read to me. (p. 376)

My loving mother introduced me to authors like Laura Ingalls Wilder, Kate Seredy, Ruth Sawyer, L.M. Montgomery, Frank L. Baum, A.A. Milne, and C.S. Lewis. During college, my love of children’s books did not wane, so I earned my undergraduate degree in Elementary Education. Throughout my schooling, both K-12 and college years, I was unaware of the need for diverse literature. During my early years, I had relatively few experiences meeting people from other cultures and very few students of color were in my classes. Looking at the class photo of 1972-73, out of the 27 students in my second-grade class, only 3 were students of color. Even in 1987, my first year of teaching in Idaho, all 29 students in my sixth-grade class were white.

After teaching for a few years, I chose to stay home once my oldest son was born. I returned to teaching full time once my youngest daughter started kindergarten in 2008. I had a lot to learn about the research conducted during my absence. Before the school year started, I was grateful for the professional development and training I was able to take which helped prepare me to meet the needs of students learning English as a second language. This time, my class was filled with a diverse group of students. For the next seven years, I grew to love the unique personalities of each child and the beauty of many different cultures. In a unit about the people in the U.S., we celebrated with students presenting something from their heritage. All four walls were covered with full sized flags from other countries. We also studied heroes like Ruby Bridges while the students learned about the history of segregation in U.S. schools. During those years that I taught second grade, I felt like each class built a strong feeling of unity and sense of community.

Although my knowledge and respect of other cultures continued to grow through the years, it wasn’t until 2019 while working on my Master’s degree in Reading and Literacy at the University of Utah that I was first introduced to an essay by Rudine Sims Bishop (2012) who eloquently stated:

It is true, of course, that good literature reaches across cultural and ethnic borders to touch us all as humans…however, for those children who historically had been ignored – or worse, ridiculed – in children’s books, seeing themselves portrayed visually and textually as realistically human was essential to letting them know that they are valued in the social context in which they are growing up… My assessment was that historically, children from parallel cultures had been offered mainly books as windows into lives that were different from their own, and children from the dominant culture had been offered mainly fiction that mirrored their own lives. All children need both. (p. 9)

This understanding motivated me to write the Worlds of Words Grant. As a new literacy coach, I hoped that my sphere of influence would extend to all the teachers that I coach and help them become aware of the need for diverse children’s literature. In our district, literacy coaches from several schools meet once a month as a cadre. Reflecting on my own experience of being uninformed about diversity, I realized that some of the other coaches might also be unaware. As a professional learning community, I decided to ask the coaches in my cadre to join me in this journey of exploring international children’s literature. In Wise and Otherwise, Sudha Murty (2002) argues that,”Vision without action is merely a dream. Action without vision is merely passing time. But Vision and Action together can change the world” (p. 177). My first goal was to help the other coaches and teachers we work with see the disproportionate representation of dominant white culture in children’s literature and the need for parallel cultures to be represented. My hope was that by achieving the first goal, teachers would be motivated to seek out diverse books and provide all students with mirrors of themselves, thus affirming cultural and ethnic value and identity through children’s literature.

In planning the grant, I wanted to include books from different countries in a variety of genres as well as books that would appeal to different age groups. My selections included: What a Wonderful Word (UK) by Nicola Edwards (2018), Funny Bones: Posada and His Day of the Dead Calaveras (Mexico) by Duncan Tonatiuh (2015), We Are Grateful/Otsaliheliga (U.S. Indigenous, Cherokee Nation) by Traci Sorell (2018), Eye Spy: Wild Ways Animals See the World (France) by Guillaume Duprat (2018), Silly Mammo (Ethiopia) retold by Yohannes Gebregeorgis (2009), Stepping Stones: A Refugee Family’s Journey (published in Canada about Syrian refugees) by Margriet Ruurs and artwork by Nizar Ali Badr (2016). I purchased 11 copies of each book and distributed them to the other coaches. I also shared the link to the Google slides that included the agenda for our meetings as well as other resources for individual books. Our first meeting was in October, so the coaches used What a Wonderful Word as the read aloud in September before our first meeting.

My purpose for reading What a Wonderful Word by Nicola Edwards (2018) was to build word consciousness and excitement about vocabulary as well as to introduce languages and cultures from around the world. One of the third-grade teachers at our school immigrated from Russia and is fluent in several languages. In the past, I have avoided some books if they have foreign words that I was concerned about mispronouncing. As I learned about the importance of diverse books, and with the internet as a tool to access authentic audio pronunciation I tackled this new challenge and learned how to pronounce several of the words. It was also helpful to have the support of this multilingual third-grade teacher as I gathered courage and read this book aloud to third graders. This teacher greets students each day in a different language and they respond in kind. With experience learning greetings, students were enthusiastic to learn other words. One of the coaches mentioned that by using the guide at the back of the book, she wrote the pronunciation of each word on a sticky note which she placed on each page. This helped her fluency while she was reading aloud to students.

I also read the story to a fourth-grade class. In this class, the excitement grew as each new word was introduced until several students were asking about specific languages like, “What word is untranslatable from Spanish?” Of course, I had to immediately skip ahead to page 20 where they were delighted to hear “Friolero – which means someone who is always cold.” Spanish is the primary language of the majority of our ELL students. Many of the Spanish-speaking students took pride and ownership of their native tongue and were eager to help me pronounce the word correctly.

For this read aloud I also prepared a powerpoint with images of the countries where each language is spoken and included videos to build background knowledge. The Hindi word Jugaad means the ability to get by without lots of resources and find new and creative ways of solving a problem, so I included the BBC News story about Jugaad Man: The Non-stop Inventor. Uddhab Bharali invents devices that improve the lives of people. The video showed Raj Rehman, a 15-year-old born with congenital amputation and cerebral palsy. Uddhab created a device that helps Raj feed himself and shoes that strap around his knees and the back of his calves, allowing him to walk on his knees. The footwear allows Raj to cross the railway line to get to school. The device strapped to his arm stump allows him to also write for schoolwork. The word from the Indigenous Australian language Wagiman is Murr-ma which means to walk through the water, searching for something with only your feet. Details provided on this page about the Wagiman language indicated that once the elderly who still speak it die, the language will most likely die with them. Another fascinating detail on the same page is a prosthetic limb developed by scientists for amputees to go from walking to swimming. I was able to find an image of a man with the prosthetic named ‘Murr-ma’ that looks similar to a fish fin.This book allowed me to efficiently expose the students to several new vocabulary words and give brief student friendly definitions. I was able to pick out and define words, such as Indigenous, prosthetic, amputees, and futuristic, from just one page. What a Wonderful Word was the perfect book to begin our exploration of international children’s books. I modeled my enthusiasm to learn words in other languages, and students responded by teaching me words from their native language. Several times, after reading to these classes, students would stop me in the hall and ask when I was going to come to their class and read a story to them again.

During Granite School District Global Community’s first meeting, the discussion focused on the need for diverse books. I shared Marley Dias’ story and her desire to read about characters that were like her. As an elementary student, she founded #1000BlackGirlBooks. I also shared the image for mirrors and windows to depict the lack of diversity in children’s books to open a discussion about the inequality of cultures represented in children’s books. One of the Literacy Coaches in our cadre developed an incentive reading program for the younger grades similar to the books the upper grades are encouraged to read for the “Battle of the Books” program in our district. Students who read the books from the list earn the button for that book to add to their lanyard. The feedback she received from a teacher at her school was a request to include more diverse books. Until that suggestion, it had not occurred to her that the books on the list were not diverse. She struggled with knowing where to find more diverse books. As a literacy community, we are sharing links to diverse book lists, so we all have those resources.

The read aloud selection for October was Funny Bones: Posada and His Day of the Dead Calaveras by Duncan Tonatiuh. I strategically scheduled this book in October since Día de los Muertos typically falls on October 31 through the first few days of November. I chose to read this book to a class of fifth-grade students since the teacher was in her second year of teaching and expressed concern about a student who seemed to read fluently but struggled comprehending. She was not sure how to help this particular student. My purpose in this read aloud was to model a “think aloud” about what I do when my comprehension breaks down and I don’t understand what I am trying to read. Before reading, I gave the class background knowledge about the author and illustrator Duncan Tonatiuh. I explained the artistic choice Tonatiuh made to create illustrations that reflect ancient Mixtec codices. The class was fascinated by the process he uses to take pictures of textures to fill in the drawings. Several of the students are Latinx and were excited to share their experience with Day of the Dead. A Polynesian student made a connection with the Disney film Coco. The Spanish speaking students were eager to help me with any Spanish pronunciation that I struggled reading. During the “think aloud” I talked about how I didn’t understand the difference between lithography and etching. The fix-it strategies I modeled were to slow down and reread.

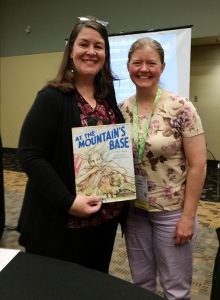

During November, Granite School District Global Community read Traci Sorell’s book We Are Grateful/Otsaliheliga. Traci is a member of the Cherokee Nation and her book expresses gratitude through all four seasons as well as shares her Nation’s rich cultural heritage that thrives today. During our cadre meeting, one of the school coaches mentioned that it would be nice to learn about more modern American Indian stories since the percentage of Indigenous children’s books published each year in the U.S. is less than 1%. Shortly after our meeting, I was able to attend NCTE in Baltimore, Maryland, my first time attending this convention. I was thrilled to meet Traci in person and listen to her on several different panels. I was excited to learn of the other books she has published, including Indian No More (2019) and At the Mountain’s Base (2019). I chose to read We Are Grateful to a second-grade class. After meeting Traci at NCTE, I wanted the students to know more about her before reading her book. I played a video of an interview she did with Rocco Staino on StoryMakers. The students loved learning details about the book. As I read the book, the students looked for the woodpecker in each illustration and practiced the pronunciation of the Cherokee words on each page. I wrote the words on large word strips so they could better see them. It was very important to me to learn how to say each word authentically. The book includes definitions, an author’s note, and the Cherokee syllabary. An audio recording of each Cherokee word is available on the publisher’s website. Live Oak Media has an audio version of the complete story available for purchase. Traci narrates along with four other narrators. The track includes authentic music and background sound effects. During the month of January, we focused on a fascinating expository text Eye Spy: Wild Ways Animals See the World by Guillaume Duprat. This beautifully illustrated and carefully researched book has interactive flaps on each page. I chose to read this book to a sixth-grade class that struggled with behavior problems throughout the year; however, as I read Eye Spy to them, I had 100% engagement. I was careful to explain the layout of the book so they would understand they needed to keep the first page extended so that they could see the key to the symbols. The classroom teacher had undergone eye surgery the previous year and shared pictures of parts of her eye that were taken for the surgery which helped build background knowledge. Several students voluntarily asked questions in response to the book. I left the book in the sixth-grade class so the students would have a chance to see the illustrations up close. Another literacy coach in the Granite School District Global community asked students to compare the eyesight between two specific animals from the book. Looking at my collection of books, I also found a book by Steve Jenkins (2014) called Eye to Eye: How Animals see the World that works well as a paired read with Eye Spy. Our book for February was Silly Mammo retold by Yohannes Gebregeorgis, a traditional tale from Ethiopia written in English and Amharic. In preparation to read this story, I asked Trhas Tafere, an immigrant from Ethiopia, to video record the book in Amharic. With her permission, this is the recording. I shared the recording with the other coaches in our Granite School District Global Community. The proceeds from this book raise money for Ethiopia Reads, a literacy campaign to get books into the hands of Ethiopian children. Ethiopia Reads has successfully started over 70 libraries throughout Ethiopia. In rural areas without roads, librarians on horseback travel from one remote area to another to reach children who have never held a book. I read Silly Mammo to a second grade class and saw the importance of the analogy of mirrors and windows when one girl, whose family immigrated from Africa, turned to two children who were whispering near her to hush them so she could hear the story better. She glowed throughout the story. The teacher of this second-grade class wanted to adapt the story into a play and have her class perform it at the end of the year. As we discussed the book in our Granite School District Global Community, one of the coaches mentioned that she was able to find Obedient Jack by Paul Galdone (1971), a similar folktale from the U.S. She read both versions to the children at her school to compare the two books. Our final meeting for the Granite School District Global Community was held Wednesday, March 11, 2020. The last book was Stepping Stones: A Refugee Family’s Journey by Margriet Ruurs with artwork by Nizar Ali Badr. We discussed the unique illustrations created with stones. Our coaches cadre was combined with another group during this meeting, so I shared the story from the foreword about how Ruurs was moved by an image posted on Facebook of a mother holding her baby and the father trudging along behind carrying a heavy load. She felt inspired to write a children’s story using this artwork. Through great effort she was eventually able to contact Nizar Ali Badr and collaborate on this touching book about the plight of Syrian refugees. Unfortunately, two days later, on Friday, March 13, 2020 we learned that Utah schools would be on a soft closure due to COVID-19. We were unable to read Stepping Stones in person so I made a recording to post on my school’s website for students. Since it was a difficult transition to online platforms while students learned from home, I felt it was important for children to see a familiar face reading a story to them. When I have the opportunity to read this story to students in person, I would like to show them a video on YouTube filmed by Adeline Chenon Ramlat to see Nizar Ali Badr create an image out of stones. The end of the book includes ways to make a difference for the many refugees throughout our world. I hope to have an important discussion with children about the type of community we create at our school to welcome all no matter what their background, ethnicity, or religious beliefs.As an educator, I am committed to find and share the new voices I discover through diverse books. The current turmoil in the U.S. and world is a testament of the need for diverse books and the need for students to see themselves as important members of a global community.

References

Bishop, R. S. (2012) Reflections on the development of African American children’s literature. Journal of Children’s Literature, 38(2), 5–13.

Felleman, H. (1936). The best loved poems of the American people. New York: Doubleday

Murty, S. (2002). Wise and otherwise. New Delhi: Penguin.

Duprat, G. (2018). Eye spy: Wild ways animals see the world. Greenbelt, MD: What on Earth.

Edwards, N. (2018). What a wonderful word. Illus. L. Uribe. London: Caterpillar Books.

Galdone, P. (1971). Obedient Jack. New York: Franklin Watts.

Gebregeorgis, Y. (2009). Silly Mammo. Illus. B. Belachew. Denver: Ethiopia Reads.

Jenkins, S. (2014). Eye to eye: How animals see the world. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

McManis, C. with T. Sorrel (2019). Indian no more. New York: Tu Books.

Ruurs, M. (2016). Stepping stones: A refugee family’s journey. Illus. N. Ali Badr. (Trans. F. Raheem). Canada: Orca.

Sorell, T. (2019). At the mountain’s base. Illus. W. Alvitre. New York: Kokila.

Sorell, T. (2018). We are grateful/Otsaliheliga. Illus. F. Lessac. Watertown, MA: Charlesbridge.

Tonatiuh, D. (2015). Funny bones: Posada and his Day of the Dead calaveras. New York: Abrams.

Teresa Johnston is a literacy coach at Silver Hills Elementary in West Valley City, Utah.

Author’s Note: The Global Literacy Communities received grants and instructional support from Worlds of Words for their work with teachers and students around global literature. These grants were funded by the Center of Educational Resources in Culture, Language and Literacy at the University of Arizona, a Title VI-funded Language Resource Center of the U.S. Department of Education.

© 2020 by Teresa Johnston

WOW Stories, Volume VIII, Issue 2 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work by Teresa Johnston at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/volume-viii-issue-2/8/.

WOW stories: connections from the classroom

ISSN 2577-0551