Exploring Global Texts with Picturebook Codes in Elementary Classrooms

Jeanne Gilliam Fain, Alexandra Hammond, Denise Lancaster, Molly Miller, Kahla Smith and Elizabeth Weisenfelder

This project utilized reflective and inquiry-based work with K-4 educators for the 2019-2020 year at a Title I school with a high population of multilingual learners. A select group of teachers (Molly, Kahla, Alex, Elizabeth, and Denise) representing each grade level at J.E. Moss Elementary School joined Jeanne (teacher educator) in regular professional development group meetings after school to explore the critical use of global texts in the classroom. The purpose of this professional development community included the creation of an intentional space to facilitate critical discussion of global literature and strengthen teaching practice grounded in principles of critical content analysis (Johnson, Mathis, & Short, 2019). Teachers grappled with the institutional standards of teaching to the test, using a scripted Language Arts curriculum, finding ways to insert global texts that are not currently on the scripted list of books to use within the Language Arts Block and an emphasis on teaching text evidence in Language Arts curriculum.

Our project began as we continually learned how to co-construct equitable and critical teaching approaches to engage all learners as they use global texts and visual analysis to think critically about illustrations and texts. We discussed the literature and piloted ways to use visual strategies with students in a supportive environment. Our reflective and inquiry-based discussions facilitated our thinking about how to adopt these visual strategies for all learners and move students to think critically and enjoy learning about global literature that related to their lives. Vertical work included thinking about literature in terms of enjoyment and this inquiry approach led to teaching across grade levels and problem solving together our approaches from our various perspectives as teachers across grade levels. We piloted some of these approaches in a small group setting with three text sets.

Background and Beginnings

J.E. Moss Elementary is a Title I School in Antioch, Tennessee. There is a high population of bilingual learners at this school, including those whose native languages are Arabic and Spanish. Our team consistently collaborated across grade levels and we met after school on Fridays. During COVID-19, we moved to meeting online via Zoom where we continued to talk about global literature and think through teaching strategies for the upcoming year.

Our team began our journey as a professional development community by reading the books in a text set over a month period. We carefully read each book and used post-it notes or highlighters to take note of interesting features of the text and illustrations. Our team worked to read deeply within a critical frame and explore the cultural contexts of the texts. To create a joint frame, we all read an article on critical literacy (Vasquez, Janks, & Comber, 2019). This article helped us to dig deeper into critical literacy and gain additional learning on visual narratives as story worlds and to use critical literacy as a lens that “provides us with an ongoing critical orientation to texts and practices and reading the world with a critical eye” (Vasquez, Janks, & Comber, 2019, p. 309). We know that reading and engaging with texts is not a neutral process. Past experiences always play a role in how we analyze and unpack texts.

This method of reading and discussing texts differs from how teachers have prepared to teach texts in the past, allowing teachers more time as a team to explore texts without immediately thinking about how to use them in their classrooms. It was critical for us to take time to enjoy the texts as readers and then move to thinking about them in terms of our roles as teachers. We learned together how to critically unpack images in a text while thinking about our identities as educators. Then, in several follow-up discussions with the text set, the group formed their own stances about a book and we moved to grappling with how to use visual analysis strategies with students (Johnson, Mathis, & Short, 2019).

Picturebook codes offer a beginning point in analysis and interpretation of illustrations. Picturebook codes that we considered included color, word/text interplay, codes of line, positionality and size, and perspective. We drew upon the work of Serafini (2014) to think about picturebook codes. We used these codes as a starting point for students to think about analysis and interpretation of visual information in a picturebook. The codes supported teachers’ and students’ understandings of the literature. Following a discussion of each book in the text set, teachers selected one book to analyze using the picturebook codes. Codes of color consist of how one uses their eyes to focus on certain elements in a visual image. Interplay refers to the relationship between words and images. Codes of line pertain to the thinness and thickness of lines used to define characters. Codes of position and size refer to where characters and objects are placed in an image and affects how readers might interpret them.

Our research question was: What instructional practices engage all learners in analyzing the illustrations in global picturebooks? We wrote notes and used post-it notes to document our thinking about the texts and recorded them in teacher reflection journals. We recorded our discussions and Jeanne selectively transcribed them. Each teacher brought students’ evidence as documented in students’ responses or field notes from conversations in the classroom. Unfortunately, many of the students’ responses were thrown away during COVID-19 in the middle of cleaning the classrooms.

Our Inquiry

We framed this collaborative professional development community on Short’s work (2017) on critical content analysis. We decided on a research purpose, focused on a few research questions, and selected and read books from text sets for our analysis. We read deeply within a critical literacy frame as we explored the cultural contexts of texts (Mobility in Journeys, Change, and Negotiation) and we read related research (two articles mentioned earlier). We took notes on the texts and teachers took field notes as we considered our personal and professional positionalities. We began to examine issues of power across texts in book club discussions. We engaged in close reading of the texts by using visual analysis as our analytical tool as we tried to dig deeper into our understandings of the books.

Our steps included the following: we selected a text from the text set, we selected a picturebook code to assist students in visually analyzing global texts from designated text set, we took field notes regarding students’ responses to the text, we brought examples of responses to the teacher community book club, and we took turns sharing students’ responses to the texts and students’ practices of making meaning with the text.

Books were selected based upon a global theme that reflected the students’ lived experiences. The following organizations were used as resources to find books: USBBY (U.S. Board on Books for Young People), IBBY (International Board on Books for Young People), and WOW (Worlds of Words). Our text sets focused on three themes: mobility in journeys, change, and negotiation. The following books were part of the Mobility in Journey text set: Dreamers (Morales, 2018), The Journey (Sanna, 2016), Thank You Omu (Mora, 2018), and Me and My Fear (Sanna, 2018).

For the purposes of this article, we focus our main understandings from three books related to our Mobility in Journey text set: The Journey, Dreamers, and Thank You Omu. We began our learning experience by reading each book, discussing them critically, and then thinking through and enacting instructional practices in the classroom.

Teachers as Readers: The Journey

We started our exploration by taking the time to read The Journey and discussed it together as a community. The Journey by Francesca Sanna (2016) is an engaging story depicting the realities of the journey of immigration. As a reader, Denise thoroughly enjoyed how the illustrations combined with the words to propel the reader into thinking of what is coming right away. She notes, “that readers can provide a powerful enhancement that words alone would have left an incomplete and inaccurate representation.” In addition, Molly thoroughly enjoyed engaging with the book. She wrote, “I was drawn to the creativity in the illustrations and it appeared to be a story that I could really enjoy. Then, I cracked open the cover and started reading. The story itself is engaging and depicts the journey of immigration in a very real, very experiential way. As a reader I was quickly engaged and involved throughout the entire story.”

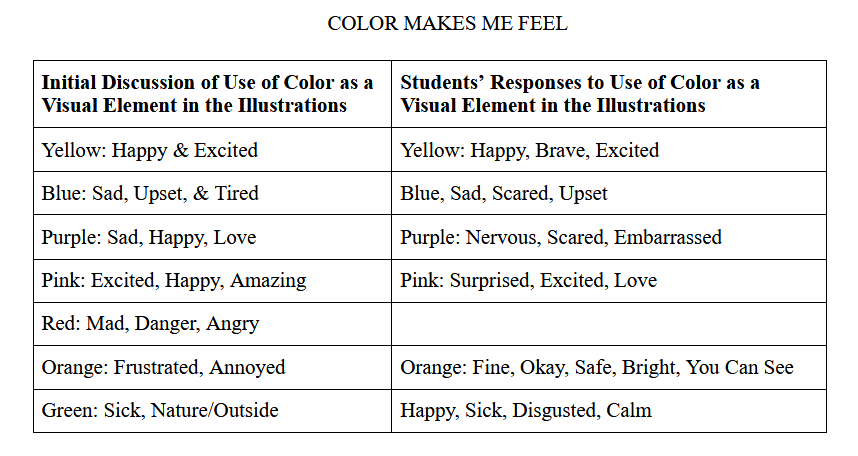

On the other hand, Kahla didn’t start off being a fan of the book. At first glance, Kahla stated, “I did not care for the large amount of black coloring used in the illustrations as it wasn’t visually appealing to me personally. As I read the story, it began to make more sense and I grew to appreciate the strategic usage of such bold, dark colors in the images. The text and illustrations worked masterfully together to build understanding of the realities of the travels of the family, and the illustrations powerfully enhanced the story.” Our professional development community then moved to discussing how we might use the book for reading instruction with students around our focus on the visual aspects of a global picturebook.Reading and Utilizing Picturebook Codes. As our learning community considered The Journey, we focused upon using the picturebook code of color as a visual tool as we thought about how to move students to critically analyze the illustrations. Elementary students across the grade levels came to the discussions with a strong background as readers in text analysis as they were accustomed to looking for text evidence as readers. Visual analysis, however, was a new experience for most of the students.

Molly, a first-grade teacher, shared her steps in trying to figure out how to use visual analysis with first-grade students. She wrote,

I reread the story through the lens of a teacher. I started formulating what strategies I’d like to use when I read the story – which could be pretty heavy for first-grade students. The first group of first-grade students came to school knowing multiple languages. They were all students who had lived in the United States for about a year, many of them even less than that and had spoken English the same amount of time. I was worried that, though they may empathize with the story, they may have difficulty accessing the language in the story. My second group consisted of students all who had additional years of experience speaking English fluently. I worried that they may not be able to make meaningful connections to the text. Through reading the book with both groups of students, however, I found that my assumptions were completely incorrect.

Molly started with a discussion about the illustrations and both groups of students were provided with an overview of some ways to think about the visual elements used in the illustrations. In particular, she talked about primary (red, yellow, and blue) and secondary colors (green made by combining blue and yellow). Molly and the first-grade students talked briefly about the neutral use of color in the illustrations including black, white, gray, and shades of brown. With both groups, Molly started off by creating a chart with the students.

Table 1. Picturebook Code (Color in Illustrations) for The Journey by Francesca Sanna (2016) (First Grade)

At first, all of the students were confused about shifting the focus of their discussion to the illustrations, but then the class read through the pages and the conversation moved to what the students noticed about the illustration in terms of color and the story. Students focused on various colors within the illustrations that Molly hadn’t noticed, and made conclusions based on the picture evidence that Molly hadn’t even considered.

As the two groups of students read and explored the text, Molly discovered that the first-grade students had full understanding of the text as evidenced through the discussion. Both groups understood the central story and proficiently accessed the story’s language. Both groups of students compassionately empathized with the story. She discovered students came to these understandings in different ways. The first group made connections to the illustrations and related to the story itself, whereas the second group of students connected to the emotions related to the illustrations and the range of the colors.

Kahla, a fourth-grade teacher, and Denise, the English Language Learner (ELL) Coach, worked together as part of a pull-in English Language Learner program model where the ELL Coach supports the needs of all learners including multilingual learners. They planned and taught this lesson together as part of an enrichment learning experience for a group of fourth-grade students.

Kahla and Denise invited the fourth-grade students to think about the power of illustrations, and in particular, they asked the students to analyze the illustrator’s use of color in this picturebook. During the initial read, Kahla and Denise tried to move students to understand the emotions behind colors and how the colors of illustrations can add to the text in a story. Interestingly, fourth-grade students grappled with understanding the illustrations and color cues. They pulled out small details instead of looking at general understandings. Fourth-grade students took the visuals very literally at first and they initially pointed out simplistic details in the illustrations. Students started out by naming relevant emotions for each color, but then both teachers noticed students overusing a personal connection strategy in a game of trying to one-up each other for unusual personal connections. Kahla and Denise realized that they needed to take a step back in their instructional approach with this text.

Kahla and Denise talked to Molly about how she found ways to move her first-grade students to think critically about the illustrations and text. Molly shared her discussion of the color of the illustrations in the text and how she created a chart so that first graders could visually discuss the power of color in a story. Kahla and Denise used the color chart idea from Molly. Kahl and Denise reread the story with the same purpose, but they refocused their teaching with the idea of using the emotions most people would think the colors represented. Students improved their discussion while connecting colors to the emotions in the story and connecting the illustrations to the words in the text.

Lessons Learned. Molly initially found herself being stretched as an educator. Molly tried to dive deeper into analyzing the colors within the illustrations and discussing the deliberate choices made by the illustrator to add meaning to the text allowed her to think about the text in a different way. The first-grade students were able to interact with the text in a different way. Next time she uses picture analysis with students, though, she plans to let them guide their own learning with less scaffolding. Students come from a variety of backgrounds and life experiences, so they bring their strengths of having different lenses of thinking to every book they read. Initially in this process, Molly was more rigid in what the colors signify visually within the illustrations.

Molly wishes she would have allowed space for more input from students. She was initially operating from a place of making sure the students were all on the same page. She mistakenly thought that each color in each illustration had specific meaning within the illustrations in the picturebook. Students had different responses to the illustrations based on their experiences, but they tried to fit their interpretations into the structure she had set during pre-reading. Molly needed to let go of some of the structures that she felt pressure to follow and let students lead more when they discuss illustrations and make meaning from a text.

According to Kahla and Denise, younger students from the professional development community group had an easier time connecting colors to emotion and transferring that to connections with this text. When instructed to analyze the illustrations, older students focused on smaller details that were less relevant to the story’s meaning. They had a challenging time visualizing the overall picture of the story. Kahla and Denise wondered if it was possible that older students are so used to being asked text dependent questions that they only focus on the text and are forgetting to visualize. They also wondered if the older students have been over taught the connection strategy and are over personalizing when they should be digging deeper as readers.

As Kahla and Denise began reading the story again with the same purpose of carefully analyzing the illustration as part of the story, students made powerful connections between the colors and illustrations to the text. It appeared as though fourth-grade students have become so conditioned to answering text dependent questions that they have forgotten how to read pictures and hone in on how much illustrations can add to the meaning of a story.

Teachers as Readers: Dreamers

Dreamers by Yuyi Morales (2018) tells the autobiographical story of Yuyi’s struggles in a new country while learning a new language. Through brilliant and colorful illustrations, we see how the character fosters a love for learning through finding a library and reading as much as possible. Every time Alex, a second-grade teacher, looked at this book, she saw something new. She loved how mood was portrayed with dull versus bright coloration. She appreciated the way the text used dual languages. In the beginning Yuyi has written amor, love, amor and at the end we see the child has written love, amor, love – symbolic of the new language being acquired by the family. Denise noticed that words are emphasized within the illustrations to represent the confusion and challenges experienced in a new culture. Yuyi uses the image of the butterfly to symbolize the journey to freedom and hope throughout the story; the size of the butterfly changes to represent where she is in that journey. The author/illustrator weaves a fantastic tale that intertwines visual spectacle with the text.Reading and Utilizing Picturebook Codes. Alex enjoyed the way students and teachers can immediately connect to the book because they will see books that they recognize and have read. She appreciated how this book presents a library card and reading in general as the key to a completely new world, including beautiful colors that jump off the page. The pictures tell a vivid story without any words. The colors all come together to create a sense of beauty and comfort.

When Alex read this book with students, she first pointed out the positioning of certain pictures and items on the pages. She wondered together with second-grade students about each of the items and reflected upon the illustrator’s choice to bring them to her new home. During Alex’s reading the students noticed the colors and identified that the author was scared in the beginning and happier by the end of the book. Alex and the second graders then identified how language would play a big part in the author coming to a new country and being confused and scared. The second-grade students noticed that the words in the sky were backwards and explained that it was because she was in the United States now, and because she was from Mexico so she did not initially understand the words.

As Alex continued reading, students noticed that the butterfly flew into the library. When the characters were in the library, students said the illustrator was imagining different things and connecting the books to things she knew from home. They noticed she was scared but that she grew more comfortable with the books. Students understood that the baby was growing so time must be passing as they continued to go back to the library. At the very end, they connected the handwriting of “Love” to the illustrator and thought they might be the same person. In this book, Alex learned the importance of book selection, positionality of illustrations, and showing students colorful and interesting ways to engage students. She learned how students connect in important ways to colors and pictures.

Denise read Dreamers with both first and fourth graders to focus on symbolic representation. This proved to be an exceedingly difficult task for the first graders. They grasped some of the basic symbolism from the text, such as bats might represent that where they are going might be a scary place. The younger students remained fixed on the meaning of the butterfly as representing happiness or joy, but not necessarily the complex representation. She later read Me and My Fear (Sanna, 2018) to help them better understand symbolic representation. This book assisted in the transition from concrete representations to more abstract representations. In the future, for younger students, she would switch the sequence of these two stories.

Our goal for the fourth graders was also understanding symbolic representation, but Denise and Kahla included the task of understanding the illustrator’s use of perspective and size. Students seemed to grasp this story. The fourth-grade students could relate to this story on a personal level which elevated their engagement. The students’ conversations were deep and meaningful. They were so enthralled with the richness of the text they kept referring to previous parts of the story and wanting us to flip back and forth as they made connections. Students loved the two different hands and handwriting on the love pages. They spent a great deal of time comparing and contrasting these pages and discussing their significance in the story. They understood that items in the backpack were from Yuyi’s past and culture.

Lessons Learned. Alex and Denise stated that they would talk more specifically about the items in the author’s backpack and how they teach readers about the main character in the story. While both books worked well with multiple grade students, younger students may need the book Me and My Fear as an introduction to more symbolic representation within the illustrations.

Teachers as Readers: Thank You, Omu

The illustrations and artwork are what initially drew Elizabeth to Thank you, Omu by Oge Mora (2018). The unique collage style intrigued Elizabeth, and she wanted to see how it was used throughout the book. She thought the rich, layered art style connected to the idea that a community is rich with different types of people. Beyond the artwork, she felt the message of this story was incredibly powerful and one that was not difficult to discern (the pattern of the story makes this possible) to even the youngest children. She appreciated the gratitude that was expressed by all of those whom Omu shared with at the end of the story, and it was powerful to see all of the different ways they repaid her. All of the characters expressed their gratitude in some way- either by bringing food they prepared, or, in the little boy’s case, a thank you card. What Elizabeth especially noted about this story is that it shows, at the end, different members of a community coming together to give back to someone who had given literally everything she had to them.Reading and Utilizing Picturebook Codes. Elizabeth asked third-grade students to examine lines and size to aid in their understanding of the story. She speculated that these visual components would be most useful to analyze this particular story. For instance, the stew itself is represented throughout the pages of the book, even when the setting is outside of Omu’s apartment. When the story takes place on the street, readers can still see a thick line of steam from the stew coming from her window. Size also plays a big role in this story. Mora emphasizes the importance of certain objects by making them large, and in some cases, so large that one object takes up two pages.

The first page of the book is bright pink, vibrant, and shows Omu taking up almost all of the first page and spills into the second. The thick line of steam from the stew spreads between two pages and goes outside. After reading this page, Elizabeth asked third-grade students what they noticed. Immediately, one student said, “the steam is going outside”

Second-grade students continued to pick up on the steam and the size of it in relation to other objects. Near the end of the book, the pot of stew is empty. The empty pot, which near the beginning of the book was shown to be a normal size, now takes up almost the entirety of both pages. Students predicted that the pot would be empty, but when they saw how it spanned two pages of the book, it was even more powerful. It was clear to them that there was absolutely no stew left–and that there had been a lot. Omu was left with nothing! It was also clear to them from the size of the pot that Omu started with lots of stew and that many people must have visited her because she was left with nothing. At one point in the story the line of stew takes up almost half of the page. Third-grade students made the connection that many people would probably be able to smell the stew and visit Omu. By the end of the story, there are so many people in Omu’s apartment that they take up both pages, which third-grade students recognized as her impact.

Lessons Learned. Second-grade students were intrigued by the unique illustrations in the book and spent a significant amount of time analyzing the illustrations while Elizabeth read to them. In typical planning sessions, the grade level team developed questions based on text features to help students meet lesson objectives and deepen their understanding of the text. Approaching this text from the perspective of illustrations was a new endeavor for Elizabeth. She noticed that many students felt comfortable interacting with the story. Discussing the illustrations provided all learners an entry point to the conversation.

Conclusion

Global literacy research has encouraged us to analyze the significance of illustrations in literature, as well as the interplay between the illustrations and the text. Elementary students are actively learning and engaged in meaningful discourse across all grade levels and it has fostered true collaboration. We have learned from each other by sharing strategies and new insights regarding the illustrations. Students have noted many interesting things that we adults had not noticed, and it has encouraged student thinking in more complex ways. We have discovered that teachers may be overusing some strategies, which we have been taught encourages thinking, only to discover that with overuse leads to confusion and errors in logic. This research is also important because our world has become increasingly image driven, and educators and literature must strive to address the trend.

As we embarked on this journey, we were first given the simple direction of enjoying the books and seeing what we recognized as a reader. The following ideas about instructional practice came from our research as we worked to engage all learners in analyzing the illustrations and text in global picturebooks:

- Teachers benefit from working together in planning with global texts to co-construct equitable and critical materials and intentional learning opportunities.

- Students are capable of complex visual strategies in the classroom. We need to keep our expectations high for all learners.

- Students can become stagnant in their responses to texts. We limit their capacity to go beyond the text when we do not use challenging strategies to push them as learners.

- Many students have become reliant on direct text-level questions and are limiting their thinking.

- Illustrations and visual images allow students to dig deeper into their understandings.

Working together as a vertical group across grade levels was significant in our explorations of these global texts and visual strategies, recognizing that we think about texts and strategies in different ways. We enjoyed learning about the different ages and responses of students, and it helped us to learn together as we worked to facilitate learning for all students using picturebook codes with global texts. Thinking together as a group helped us to explore our initial joint understandings of how to use global texts powerfully in the classroom.

References

Johnson, H., Mathis, J., & Short, K. (2019). Critical content analysis of visual images in books for young people. New York: Routledge.

Serafini, F. (2014). Reading the visual: An introduction to teaching multimodal literacy. New York: Teachers College.

Short, K. (2018). What’s trending in children’s literature and why it matters. Language Arts, 95(5), 287-298.

Vasquez, V. M., Janks, H., & Comber, B. (2019). Critical literacy as a way of being and doing. Language Arts, 96(5), 300-311.

Children’s Literature Citations

Mora, O. (2018). Thank you, Omu. New York: Little Brown.

Morales, Y. (2018). Dreamers. New York: Neal Porter.

Sanna, F. (2016). The journey. London: Flying Eye Books.

Sanna, F. (2018). Me and my fear. New York: Neal Porter.

Alex (Alexandra) Hammond teaches second grade at J.E. Moss Elementary in Antioch, Tennessee.

Denise Lancaster is an ELL Coach at J.E. Moss Elementary in Antioch, Tennessee.

Molly Miller teaches second grade at J.E. Moss Elementary in Antioch, Tennessee.

Kahla Smith is a fourth grade teacher at J.E. Moss Elementary in Antioch, Tennessee.

Elizabeth Weisenfelder teaches third grade at J.E. Moss Elementary in Antioch, Tennessee.

Jeanne Gilliam Fain is a Professor in the Department of Education at Lipscomb University in Nashville, Tennessee.

Authors’ Note: The Global Literacy Communities received grants and instructional support from Worlds of Words for their work with teachers and students around global literature. These grants were funded by the Center of Educational Resources in Culture, Language and Literacy at the University of Arizona, a Title VI-funded Language Resource Center of the U.S. Department of Education.

© 2020 by Alex Hammond, Denise Lancaster, Molly Miller, Kahla Smith, Elizabeth Weisenfelder, and Jeanne Gilliam Fain

WOW Stories, Volume VIII, Issue 2 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Based on a work by Alexandra Hammond, Denise Lancaster, Molly Miller, Kahla Smith, Elizabeth Weisenfelder, and Jeanne Gilliam Fain at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/volume-viii-issue-2/4/.

WOW stories: connections from the classroom

ISSN 2577-0551