ESL Students Find Themselves and Expand their Horizons through Global Literature

By Heather O’Leary

Twenty-five enthusiastic ESL students, grades K-6, from a small urban school district, participated with me in the Tri-Cities Global Literacy Community. Our elementary school of 400 students is one of nine in the district and has a free lunch rate of 81%. Our school is considered “high needs” and is deemed “low-performing.” Although these labels bring frequent accountability visits, rigorous reporting requirements, and implementation of yearly improvement plans, they fail to convey the work and spirit of our ESL classroom. We have a lively and productive learning community and are fortunate to have the support of a talented and energetic principal.

Our participation in the Tri-Cities Global Literacy Community helped keep our focus on what is important: being a part of a learning community that reads authentic, high-quality literature to feed our knowledge and thinking about ourselves and the world. As a teacher with 20 years of experience, it provided me with a deeper appreciation of my ESL students’ unique strengths as a result of “living in two worlds.” I always try to be conscious of, and open to, the points of view of my students and their parents. This year’s project helped me find more ways for my students to express their perspectives and acknowledge them more. As a result, I felt we tapped into a deep well of knowledge, feelings, and ideas which helped develop a greater sense of community, mutual respect, and sharing of ourselves that was both motivating and a basis for deeper academic study.

ESL Students, the ESL Program, and Global Literature as a Good Fit for ESL

In my school, ESL students leave their classrooms for English instruction for three to six hours a week depending on their level of English language proficiency. We try to accomplish an awful lot in that time—from teaching newcomers “survival English” and helping them adjust to a new school, culture, and language – to helping advanced students learn the nuances of the language, expand their vocabulary, build their content knowledge, and hone their skills in order to function on par academically with native speakers of English. With the range of diverse needs, grade levels, and English-proficiency levels, scheduling and grouping students is a huge challenge. Using global literature to teach thematic units helped bridge many differences between students. It helped me offer instruction appropriate to each student’s age, interest, and level of academic challenge. Texts sets connected to global themes and stories about historical figures were supported with video and audio clips, and real photographs. This enabled all students to find a foothold in the material.

Using authentic global literature provided my students the opportunity to see themselves in the books we read and to see their memories, experiences, and background knowledge as a strength in their learning and reading. For example, when a second grade girl from Sudan read Golden Domes and Silver Lanterns: A Muslim Book of Colors by Hena Khan (2012), she gasped at each page because the pictures and words resonated so deeply with her.

She looked at one page with wonder, her finger moving from right to left under Arabic text and said delightedly, “I can read this! It is written in Arabic and I am learning Arabic at Saturday school!” She was thrilled to see an illustration of a lacy silver lantern and related to us that she and her aunt carried beautiful lanterns like that. She had a genuine connection to each page. She took the book home to keep along with others she loved, such as Sitti’s Secrets by Naomi Shihab Nye (1994).

The ESL population in my school is diverse. Some are recent immigrants, while others were born in the U.S. and have not ever visited their parents’ native country. Some are struggling to retain their culture, language, and identity. This is especially true of the children from Puerto Rico who are American citizens, and sometimes have earlier exposure to English. Sometimes they are more assimilated to American mainstream culture than a student from the Middle East, Asia, or Africa. Often these students seem to identify with mainstream American culture but have a deep desire to stay in touch with their identity as Puerto Rican people who are bicultural and bilingual.

As members of the Tri-Cities Global Literacy Community, my elementary ESL students and I have grown in knowledge, engagement, and appreciation of our own cultures and that of others. Reading books about people from around the world reminded some of us of home, our parents’ stories, our native languages, and our own experiences. Other times, we read about our friends and learned things about them that we didn’t know before and appreciated them, their cultures, and their traditions more than ever. We saw our talents, literacy, and awareness of the world grow. It was wonderful learning about our similarities and differences. We gained increased awareness of geography, history, culture, and of inspirational people, some of whom are famous and some who are not.

The books we read in ESL gave acknowledgement to the fact that the students’ cultures and native languages are valuable resources that enrich them and their understanding of the world and everything that happens at school. While cultural differences have always been respected and embraced in ESL, the U.S. and English were two big commonalities all the children shared, regardless of their country of origin, so the focus was often on similarities rather than differences. This year, by using global literature, the focus of learning changed to invite students to talk about their dual cultural and linguistic identities. I underestimated how much my students would enjoy and learn from it. I was also pleased with how much they began to recognize and take pride in their biculturalism and bilingualism and how much recognition they began to get from their peers for being people with special strengths rather than students who “need extra help.” This year when I walked into classrooms to shepherd my students to ESL, at least one of their peers would say,” I want to come and learn another language, too!” We did, incidentally, have a “Bring a Friend to ESL” day where friends were given a glimpse into our ESL world and feted with a special lunch.

One particularly successful group who immersed themselves in global literature was a diverse group of ten students in grades 3-6 who met for an hour three times a week for much of the year. A chart showing gender, grade level, native country, and English proficiency level is shown below. Four of the students have Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) and receive special education services. All the students came to view themselves as readers and writers with special strengths and knowledge.

| 3rd grade boy | Puerto Rico | Intermediate |

| 3rd grade girl | China | Intermediate |

| 3rd grade boy | Mexico | Beginner/IEP |

| 3rd grade girl | Mexico | Advanced |

| 4th grade girl | China | Advanced |

| 4th grade girl | Puerto Rico | Beginner/IEP |

| 4th grade girl | Yemen | Advanced |

| 5th grade girl | Dominican Republic | Intermediate/IEP |

| 5th grade girl | Puerto Rico | Advanced |

| 6th grade girl | Puerto Rico | Beginner/IEP |

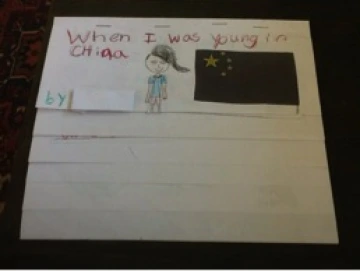

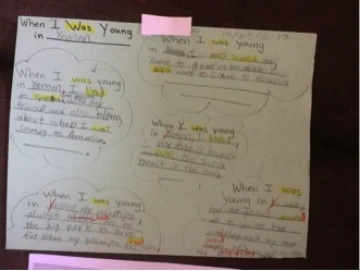

A Mentor Text Inspires Our Own Memoirs

Cynthia Rylant’s (1982) When I Was Young in the Mountains inspired our own “When I Was Young” books. Some students wrote about their native countries: When I Was Young in Yemen, When I Was Young in Puerto Rico, When I Was Young in Mexico. Others chose to write about their memories in America: When I Was Young in Pre-School, When I Was Young at Yates (another school in our district which the student attended her first year after arriving from Puerto Rico). Students worked in pairs to help each other plan their writing and complete a basic graphic organizer. They bounced ideas off each other, edited their writing based on ideas they liked in their peers’ writing, and shared in front of the group. Students brought precious photographs from home to be photocopied to help illustrate their books. We printed pictures of flags and landmarks and other photos they requested from the Internet, and they filled in with their own drawings. All the while, our language objective was using past tense verbs. The students presented their books to the class, and I videotaped them reading their books. Some students chose to bring a friend to the front of the room when they read their story to the class. There was applause and appreciation for each child’s story and an eagerness to share their books with their peers and parents.

When we read Rylant’s book, one of the third graders from Mexico was struck by the similarities of the narrator’s experience in the distant past in rural America and his own memories of living in Mexico. While some of his peers were surprised to read about the narrator’s simple life with her grandparents and needed some explanation for some of the events in the book, this third grader knew what an outhouse was, describing life in a house with a dirt floor and pumping water from a well to drink. He knew what it was like to live close to the land. His text read:

When I was young in Mexico, sometimes we drank water from our hands instead of from a cup. When I was young in Mexico, we spoke Trique and Spanish. Now I speak Spanish and English. When I was young in Mexico, there were bathrooms outside and inside. When I was young in Mexico, my dad and everybody killed a cow and we ate the cow. When I was young in Mexico, I lived with my mom, my dad, my brothers, and sister, and grandma and grandpa.

A fourth grader from Yemen brought beautiful photographs to illustrate her book relating her memories of her grandparents and her mixed feelings about coming to America. She loves her new life, has adjusted beautifully, and fits in well with all of her peers. It was fascinating for all of us to catch a glimpse of her world in Yemen and to know that she was both scared and excited about leaving Yemen for America. She wrote:

When I was young in Yemen, my grampa always took me to the big park to have fun when my grampa had time. When I was young in Yemen, I was scared to come to America because I didn’t want to come to America. When I was young in Yemen, our neighbors invited us to go to the wedding and my mom said yes. We got to see the beautiful lady. When I was young in Yemen, I liked to spend time playing with my friends and also talking about when I was coming to America.

As we thought about our past experiences and some shared stories of being immigrants, we read about immigrants from Japan and Mexico, including two multicultural books about grandfathers: Allen Say’s (1993) Grandfather’s Journey and Eve Bunting’s (1994) A Day’s Work.

These books sparked conversation as students interviewed each other about being bilingual and talked about their experiences translating for others as Francisco did for his grandfather in the Bunting book. Students shared stories about awkward situations they commonly find themselves in when they must translate for adults.

Their feelings about it ranged from a sense of pride and happiness that they could help their parents at the doctor or at the store to being very scared and frightened to be in that position. Many shared the experience of being afraid of what would happen to their parents if they needed them to translate and they were in school and not there to help.

One fourth grader from Yemen said, “I worry my mom will get lost and won’t be able to ask anyone for help!” The students eagerly requested a reread of Grandfather’s Journey as they related to the feeling of wanting to live in two places like Grandfather and the grandson in the Say book wanted. The grandson said, “…the moment I am in one country, I am homesick for the other.”

Appreciating Access to Schools and Libraries

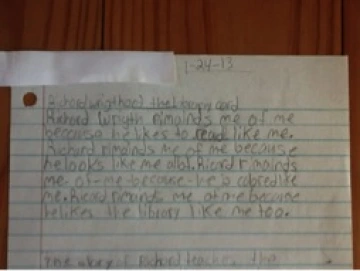

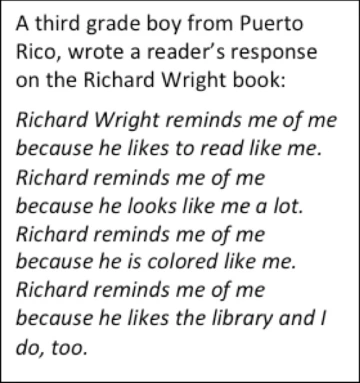

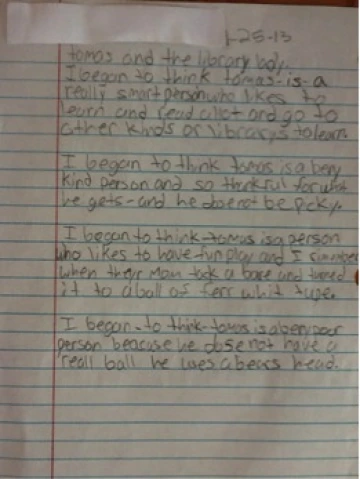

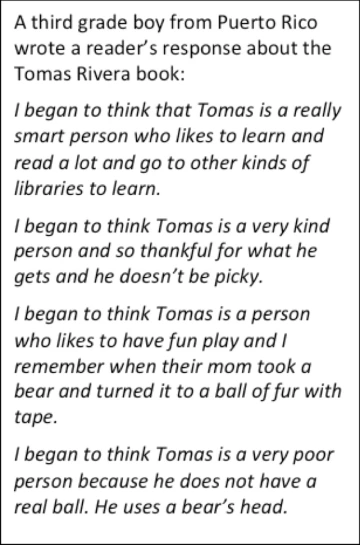

Two fabulous books, Tomás and the Library Lady by Pat Mora (1997) and Richard Wright and the Library Card by William Miller (1999) provided material to write compare/contrast essays as well as informal reader responses. Our theme was the wonderful possibilities that libraries and education hold for us.

Both main characters heroically pursued education, knowledge, and the opportunity to use the library which we often take for granted. The students were touched by how both characters were poor and had to find reading materials in garbage cans, how Richard had to warm up beans using tap water running over the can, and how Tomás’s mother made a ball for her children from an old teddy bear.

We also fell in love with the story of Ron McNair, an African-American astronaut who died in the Challenger space shuttle explosion in 1986. He had challenged segregation at the public library as a boy in South Carolina. We listened to McNair’s brother tell that story on a wonderful audio on NPR’s Story Corps. We read the story in Ron’s Big Mission by Corrine Naden and Rose Blue (2009) and we watched film of Ron McNair as well as archival footage of the sad and fateful day when he died in the Challenger explosion.

One Person Can Make a Difference

The theme of using education to make a positive difference in the world was conveyed through books that we added to our favorites: The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind by William Kamkwamba and Bryan Mealer (2012), and a collection of books about Wangari Maathai: Wangari’s Trees of Peace: A True Story from Africa by Jeanette Winter (2008), Mama Miti by Donna Jo Napoli (2010), Planting the Trees of Kenya: The Story of Wangari Maathai by Claire A. Nivola (2008), and Seeds of Change: Planting a Path to Peace by Jen Cullerton Johnson (2010).

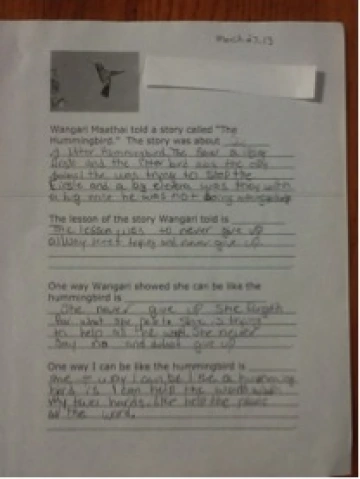

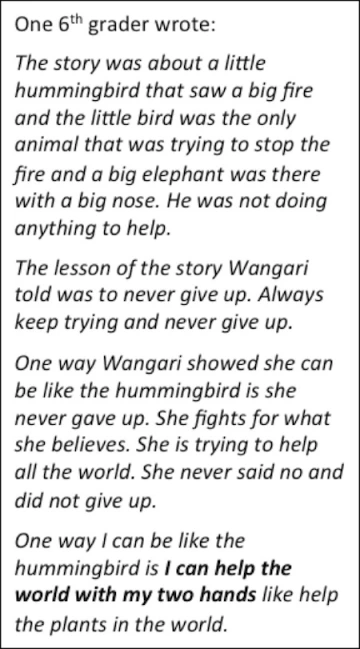

We empathized with Wangari Maathai who was shocked when she saw the effects of deforestation in Kenya that occurred while she was away from her country studying for her doctorate. She used her knowledge of science to combat the problem by planting trees and encouraging others to do the same. This led to the Green Belt Movement. We were inspired by the metaphorical story she told (in a video clip) of a hummingbird trying to put out a massive fire while bigger animals, with more power to help, stood by paralyzed by the enormity of the task. The hummingbird, although small, was doing his best, and Wangari said she was like the hummingbird—just doing the best that she can.

We were also inspired by William Kamkwamba who educated himself to solve a life-threatening problem in his country: drought and famine. We read that he was so hungry he felt like he had a monster his stomach. We felt genuine sadness when he told of having to drop out of school because his family didn’t have any money for tuition. He didn’t give up on his education. He read books in English, a foreign language for him at the time, and built a windmill to create electricity for a water pump. He saved his village from starvation. Being bilingual themselves, many ESL students marveled that William had the patience and perseverance to painstakingly translate technical directions, written in a foreign language, so that he might be able to find scrap material to build the windmill. Another inspiring connection to the book was that the illustrator, Elizabeth Zunon, was herself an ESL student in a neighboring town.

Civil Rights and Social Justice

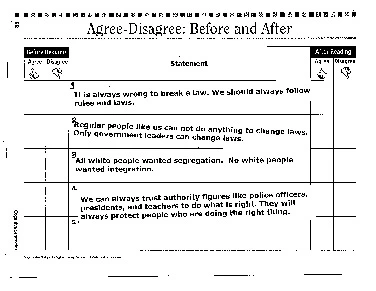

While reading about Richard Wright in Richard Wright and the Library Card, we delved into the Civil Rights Movement. Even though we felt we knew a lot, we certainly learned a lot. We started with an anticipation guide with four statements to agree or disagree with before we started our reading and study. We were all certain that the police are always right, that there were no white people who supported civil rights, that we should follow all laws, and that all people in jail must have done something so bad that they deserved to be there.

We then read Freedom on the Menu: The Greensboro Sit-Ins by Carole Boston Weatherford (2005) and watched video of civil rights protestors getting trained in nonviolent protest and noticed that there were some white protestors being trained, too. We watched video of the lunch counter sit-ins and saw how the training was put into action. This brought a deeper understanding of a few important things: When police were called, they were there to jail the protestors, not the white people who were pushing and shoving and trying to antagonize the protestors by pouring hot coffee or ketchup all over them. Also, as soon as one group of protestors was taken to jail, there was another group waiting to take their place, and they actually wanted to go to jail to make a point. We knew we were on their side, and we were amazed by the singing, happiness, and solidarity of the protestors in jail.

This book inspired a spontaneous idea in some of the students who wanted to “role play” the lunch counter sit-ins. The students lined up some chairs to represent the counter. A Chinese girl whose family runs a restaurant said she could be the waitress behind the counter. A black boy from Puerto Rico, who was a driving force in this role play, insisted on taking the lead role of Martin Luther King, Jr. because he felt he most resembled him. A number of students wanted to be protestors at the lunch counter. Other students took on the roles of the police and white counter-protestors chanting “Two, four, six, eight, we don’t want to integrate!” One girl from the Dominican Republic didn’t feel comfortable being a police officer or a protestor and created a role for herself: she chose to be a passerby who encouraged the protestors, proclaiming, “You are doing the right thing.” I videotaped. The third grader playing Martin Luther King, Jr. announced that he would bring his “Sunday clothes” the next day so that we could do the role play again and this time, he’d really look like Dr. King. He followed through and did a wonderful job. No teacher could ask for more intense learning and engagement than these third through sixth graders demonstrated.

What also amazed me was the deep level of vocabulary learning that happened. Students learned what it means to be civilly disobedient—that it requires breaking rules when laws are unjust. My students could apply this complex concept to other situations. When we watched a video clip of Kenya’s former president denouncing and deriding Wangari Maathai, he dismissed her as a “disobedient woman.” One of my students, who has a learning disability, piped up, “Oh she’s disobedient! Like Martin Luther King!”

Global Literature and Widening the Curriculum

Making global literature the centerpiece of our year helped keep instruction focused on material that was engaging, challenging, and interconnected. We were armchair travelers as the globe was always on the table while we read, and students looked up the places where the stories took place. Geography started to become ESL students’ strength, especially in relation to their peers. They could pick up the globe, find our location, their native country, and locate William Kamkwamba’s country in Africa or show the distance Wangari Maathai travelled by tracing their finger on the globe from Kenya to the American Midwest where she studied science. We studied the environment, learned vocabulary for the parts of a tree, from roots to trunk to canopy. We talked about racism, protest, and civil disobedience.

In other words, we studied a rich curriculum. We did not fall victim to the narrowed curriculum that has been the unintended consequence of testing and accountability. We resisted the pressure to raise test scores by narrowing the curriculum so that students spend their time on basic skills, learning test-taking strategies, and practicing the “test genre.” Social studies, science, and the arts can sometimes be abandoned so that students spend more time preparing for the tests, reading isolated passages, drilling on practice multiple choice questions, and anticipating what the test-makers and scorers are going to want to see in their written responses. Obviously, we wanted to proceed in a different direction. Global literature helped us stay open to the world, look deeper into a variety of interesting topics, and see the connections between them. We have lots of plans for the coming school year to keep building on and connecting to what we’ve learned and to pursue some interests we discovered.

References

Blue, R., Naden, C. J., & Tate, D. (2009). Ron's big mission. New York: Dutton.

Bunting, E, & Himler, R. (1994). A day's work. New York: Clarion.

Johnson, J. C. & Sadler, S. L. (2010). Seeds of change: Planting a path to peace. New York: Lee & Low.

Kamkwamba, W. & Mealer, B. (2012). The boy who harnessed the wind. New York: Dial.

Khan, H. & Amini, M. (2012). Golden domes and silver lanterns: A Muslim book of colors. San Francisco: Chronicle.

Miller, W. (1999). Richard Wright and the library card. New York: Lee & Low.

Mora, P. & Raul, C. Tomás and the library lady. New York: Knopf.

Napoli, D. & Nelson, K. (2010). Mama Miti: Wangari Maathai and the trees of Kenya. New York: Simon & Schuster .

Nivola, C. A. (2008). Planting the trees of Kenya: The story of Wangari Maathai. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Nye, N. S. & Carpenter, N. (1994). Sitti's secrets. New York: Four Winds Press.

Rylant, C., Goode, D., Durell, A., & Levinson, R. (1982). When I was young in the mountains. New York: Dutton.

Say, A. (1993). Grandfather's journey. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Weatherford, C. B & Lagarrigue, J. (2005). Freedom on the menu: The Greensboro sit-ins. New York: Dial.

Winter, J. (2008). Wangari's trees of peace: a true story from Africa. Orlando, FL: Harcourt.

Heather O'Leary is an ESL teacher at Hamilton Elementary School in Schenectady, New York.

WOW Stories, Volume IV, Issue 6 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesiv7.