How a Social Action Project Revitalized a Third Grade Response to Intervention Reading Group

By Maggie Burns

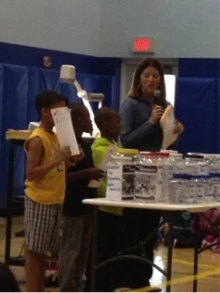

It is time for our school’s Morning Program. The entire elementary school, grades K-5, has gathered in the school gymnasium to celebrate the social and academic achievements of all members of the school community. Third grade boys, excited and nervous, stand in front of the whole student body ready to present a social action project they designed after engaging with an inspiring text in their reading group. They have spent the past few weeks crafting a “script” to present to the student body, outlining their plan. Large plastic jars line a large folding table, while a Prezi slide show projected on the wall behind them helps illustrate their points.

The boys begin to speak to their peers about raising money for children in rural Colombia, South America who have no schools or books. They smile as they take turns passing the microphone to each other as they proudly explain this project to the school community. When they are done speaking, they excitedly hand out jars to each class that will be used to collect money for their cause.

Two and a half years ago, I left my role as a classroom teacher of 14 years to become a reading specialist. I made this transition fully aware that it would be a significantly different role. Even more changes were on the horizon. New York state adopted the Common Core, initiated a new teacher evaluation system, and my school district piloted a Response to Intervention (RtI) program.

In the midst of these changes, I was also nearing the completion of a second masters degree in Literacy and was eager to implement instructional designs and engagements that I knew could help accelerate, motivate, and engage my students. But how? I was becoming very frustrated because my practice did not always align with my belief system. My students were doing what I asked of them, but were often exhibiting reading behaviors that reflected surface level understandings at best. Maybe, I thought, they were frustrated as well because I was not meeting their needs as readers and writers? Maybe there was more that I could do?

I was fortunate to be a part of the Tri-Cities Global Literacy Community, an inquiry group studying global literature use in classrooms. I was initially hesitant to join the group because of what I perceived as the instructional constraints of my job. How would I be able to use global literature with my struggling readers during my daily half hour with them? Given the expectations of my job, could I pursue teaching in alignment with the focus of our inquiry group?

The group broadened my perspective on teaching and learning. This occurred not only in terms of deepening my knowledge and understanding of global literature and the many and varied ways to use it across grade levels and curriculum, but also in terms of opening up the sense of isolation many teachers feel in general. The sense of urgency and worry associated with the adoption of the Common Core and the new teacher evaluation system was minimized for me with the exposure to other teachers, schools, and perspectives I may not have experienced had I not stayed with the group.

During my time in the inquiry community, I reflected on my feelings of constraint and I realized that there was a lot more within my control than I had thought. Over time, I realized that although I did not have the same kind of control over my curriculum that others in the inquiry group had, I did have control over the decisions I made within my school’s reading program. I had choices within my implementation of the Fountas and Pinnell Leveled Literacy Intervention System (LLI) in terms of the texts, the delivery, and the approach. Upon examining the texts included in the intermediate LLI Kit, I found there were many texts that reflected multiple perspectives, cultural differences, and social action.

I decided to make some changes. First, I decided to choose texts that reflected global perspectives and that matched my students’ reading levels. Next, I decided to listen more and talk less. When I did talk, I focused on asking more open-ended questions in an effort to get the students thinking about the text. Lastly, I decided that I would respond to students’ questions with questions in an effort to construct a possible answer in collaboration with them, instead of giving over the information.

To illustrate what occurred when I made these changes, I describe in detail how my third grade reading group responded to a particularly compelling text describing one man’s efforts to bring books to kids in rural parts of Colombia.

The Reading Group

My third grade Response to Intervention (RtI) reading group was comprised of four boys, Rakim, Eric, Jamal, and Sean (all names are pseudonyms). The boys were reading significantly below grade level. They were 9 years old and had been with each other in the same class since first grade. The boys attend our school in which 86% of the students receive free or reduced lunch. All four boys are African American, and all four boys had received intervention services for reading and math since first grade.

This group had incredible chemistry. They truly enjoyed each other. When we met, they entered the room chatting happily with each other about the events of their day. They were eager to share their stories with me and generally inquisitive about the world around them. Their classroom teacher promoted inquiry in the classroom and was very supportive of their interests.

Earlier in the school year, the boys made great efforts to engage in the tasks and texts I presented, but something was missing. We were all being compliant, but the engagement and motivation on both sides (mine and theirs) was missing. I felt by creating a more collaborative environment, the students would feel more in control, more engaged, and more motivated.

Once I decided to make changes in my approach, one of the first readings I presented to the third grade group was called “Alfa and Beto: The Biblioburros” (Morrow, 2013). It was a nonfiction text about a man named Luis Soriano who brought books to children in rural communities in Colombia, South America on his two donkeys, Alfa and Beto. This text instigated a change in this group that I could have never imagined.

When I introduced the text to the boys, they immediately began to read. As the boys read, they began to verbally and non-verbally react to the text. Rakim blurted out, “What? …Where is this?” Jamal responded, “Wait a minute… He rides a donkey…He broke his leg?” Eric exclaimed, “Wait ‘til you get to this page and it tells you how…You have to read more.” The boys were reading, reacting, and responding to the text without my input. They were helping each other make sense of it. They were questioning it as they read and then going back into the text, hungry to see what happened next. When they looked to me in the midst of all this, all I could do was ask, “What else are you thinking?” What ensued was a conversation initiated by the boys about how people lived without school or books. They were amazed to find out that some kids didn’t have the opportunities they had to go to school and learn to read. They wanted to know where this country was, what it was like, and how Luis really got the books to the kids.

They asked if they could reread the book to see if they missed anything. They had never made this request before. The texts we had engaged in up until this point were more fictional stories with familiar plot lines and characters. This non-fiction text was very different as it examined a different culture, people, and economic context. As they read it again, they continued to discuss with each other their findings and reactions. I did not interrupt, or try to explain anything until they asked it of me. I remained an observer allowing them to move through the text independently and with each other.

The next time we met, I presented the boys with a video I found on Luis and his Biblioburro. This made the text even more real to them. The boys asked if they could figure out something to do to help Luis and the kids. They brainstormed during our session together and came up with the idea of a fund drive to raise money to send to Luis so he could buy more books. The video had raised the issue of maintaining and growing the library in an effort to expose more children to books and reading.

Our school had engaged in a Penny Harvest the year before. The boys thought we could raise money like the Penny Harvest. They were concerned, though, that pennies would not bring in as much revenue as they would like. They debated with each other about collecting quarters or dollars. They decided that quarters would be more accessible because “some families are going through hard times…and everyone has quarters.”

During the subsequent weeks, the boys engaged in a myriad of engagements centered on their social action project. They had conversations and debates over how to proceed with their fundraiser: how to get the word out, how to collect the money, how to keep people interested. Once they solidified their plan, we made a list of action steps to help them stay on track and meet deadlines. State testing presented a barrier for a two-week window during our planning and action step period. This frustrated the boys at the time; however, they were immediately back on track once testing ended.

The Concept of Audience

Many of the engagements the students instigated as part of this project involved reading and writing. Three such engagements specifically involved getting the word out about their project to the Principal and the student body. The first engagement involved crafting a “script” to read at our school’s Morning Program to present the project and the collection jars they had made to the student body. Their feeling was that if they were to just talk off the cuff, they would forget some important information. So they crafted a script and assigned parts for each group member to say.

When the boys began to craft the script they experienced difficulty in deciding what to say and how to say it. They each had a different idea about how to present the information and no one agreed with each other. I stepped in at this point and talked to them about the concept of audience and invited them to consider who they were writing the script for. This concept of considering audience was surprisingly unfamiliar to the boys. Once they wrapped their heads around the idea of audience they began to work together more collaboratively to create their script, debating what to add or take away, what to say, and how to say it. The conversations were lively and enthusiastic.

Once the script was complete, they realized they had not asked the principal for permission to engage in the fundraising and felt they should ask him. One of the boys requested if they could use my email account to send an email from the group to our principal. They then began to craft their email. One of the boys suggested using their script as the email since it had all the important information in it. I supported their decision as they attempted to do this. When they read it over, they felt it did not sound right. This gave us another opportunity to discuss the concept of audience and how different audiences require different writing. We talked about how writing to the Principal in an email was different than writing a script to present to the student body. Rakim said, “He is the boss of the school, we have to be even more respectful…We also have to convince him that this is a good idea.” Eric stated, “It can’t be as long as our script, because he is a busy man.”

The boys decided to use the script as a guide, and began to craft the email. When they wrote both pieces the group worked to choose their words carefully, they reread their writing before they wrote more, and they listened to what each other had to say. It was truly amazing how empowered the boys felt as they created these writing pieces together in a collaborative way. What added to this feeling of empowerment for them was the validation the principal gave them when he immediately responded to their email and followed up with a visit during their RtI time to discuss the project with the boys.

Lastly, the boys wanted to create posters to advertise their project. They felt it was important that students be reminded with posters to bring in their quarters. I asked them what they needed. They wanted me to print out various size quarter pictures to place on their posters. Again, the concept of audience came up in relation to the poster. Marc said, “We can’t put everything we wrote in our script on the poster…there have to be less words.” Eric said, “We HAVE to put Quarters for Colombia on our poster… that has to go on.” Jamal added, “Let’s put bring in your quarters for Luis and the kids in Colombia.”

Fluency and Feedback

Once the email was sent, the posters were made and the script was set, the boys felt it was important to practice the script. Rakim was specifically concerned with his fluency. He said, “Mrs. Burns, I don’t want to stutter on my words. I want to know them and sound like I am talking -- not reading – when we are in front of all the kids.” The others agreed. They asked if they could use the time during RtI to practice. I agreed to use some of our time and asked if I could record them so they could hear themselves. They were very eager to hear themselves so we engaged in the practice at the beginning of our sessions.

When the students heard themselves they were stunned. They began to comment on their own reading and the reading of others. Some of the comments were less than complimentary, urging the speaker to sound louder, read faster, and try harder. When this started to happen I asked the boys how it felt when someone made a negative comment like that. They all responded that they did not care for it, so I explained the concept of feedback to them and asked if they wanted to try to give more feedback instead of criticism. They agreed and decided when they commented they would like to start with something they liked about how the reader spoke. One student said, “Mrs. Burns, you always start with what you like about our reading. Let’s do that!” (I never even thought they noticed this.) So we audio recorded the reading and gave feedback based on a fluency card the students regularly used in the group, making sure to always begin with a positive comment.

This practice of audio-recording, reading, and giving feedback prior to a public presentation for a real audience brought the students’ performance to another level. Each time they practiced they became more fluent, expressive, and confident. Each time they gave feedback they made sure to begin with the positive and look the speaker in the eye when they spoke to him. Each time they read, they had a sense of purpose.

This was a very organic experience for the boys because they had real purpose as a motivator. They chose to engage in most of these activities. They came up with the ideas, the engagements. They wanted to create a script. They wanted to write an email. One boy stated, “We never get to do what we want and you are letting us.” Their efforts resulted in a stellar presentation introducing their project to the school body at the Morning Program and the raising of an impressive amount of funds for their project.

Quarters for Colombia

After their first presentation in May, the boys made another special guest appearance at our school’s last Morning Program in June, two weeks before school ended. It was their intention to share how much money the school had collected for the children in Colombia. Prior to this, the group asked to meet with the principal to reveal the dollar amount to him and ask if they could speak about their success at the last Morning Program. The principal met with them immediately after they counted all the quarters they collected. The following is an excerpt of part of the conversation:

Rakim: Mr. Smith, you are not going to believe how much money we raised for the kids in Colombia….

Eric: We have so many quarters…..

Marc: It was hard to count them all…it was a lot!

Principal Smith: Well, how much money is it?

Rakim: Can I tell?

Jamal, Marc, and Eric: Sure…sure.

Rakim: Four hundred dollars even!!!! Can you believe it?!

Principal Smith: Wow! Boys, you really did it. You should be so proud of your selves! You are helping so many kids to read. How do you all feel?

Rakim: Great! So great! I can’t wait to tell my grandmother!

Marc: I can’t believe how much we got. Can we tell the kids at the next Morning Program?

Principal Smith: Sure, do you want to write up another script?

Eric: No, we just want to say it.

Rakim: We just want to say what we did, how much money we raised. Can we just have the microphone and do that? We don’t have to say as much as we did the first time! We just want to thank the kids who brought in all that money.

Principal Smith: Sounds great to me, if you are comfortable with that!

Initially inspired by one man’s efforts to bring books to children in rural Colombia, the boys mobilized their literacies to think beyond themselves, to develop a plan of action, and to communicate with a wide range of audiences. While they were doing so, they developed a greater sense of agency as readers and writers because they had a purpose that drove and motivated them. These boys continue to serve as an inspiration to me as I continue to seek out possibilities for revitalizing my own teaching with global perspectives.

References

Morrow, P. (2013). Alfa and Beto: The biblioburros (abridged version). In I. C. Fountas & G. S. Pinnell, RED leveled literacy intervention student test preparation booklet (pp. 19-20). Portsmouth, NH: Heinneman.

Maggie Burns is a Reading Specialist at Delaware Community School in Albany, New York.