“Seeing with New Eyes”: Envisioning Learners as Travelers in New Worlds

By Simeen Tabatabai

“…the real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new lands but in seeing with new eyes.”

Marcel Proust, Remembrance of Things Past

Learners as Travelers: The Teacher

What is my way of reading and thinking about a piece of literature? What do I bring of my own self to how and what I teach? I am continually reflecting on these questions as I teach reading to fifth graders at a suburban school in a mid-size city in the Northeast.

While they are still fourth graders, I have my future students visit my class and tell them a little bit about myself. They come into my classroom on the last day of school before their summer vacation, and they are invariably intrigued by this introduction to their soon-to be-fifth grade reading teacher. I am a little different from the other teachers that they have had. I grew up in Africa at a time when African nations were gaining their independence from their colonizing countries. My parents joined the influx of people from all over the world that came to Africa to bridge the gap in manpower resources that were needed as these nations reorganized their institutions. As a child, I remember being in a class where the 35 students all spoke different languages at home, some speaking multiple languages! I grew up in a truly multicultural environment and had to navigate differences in cultural attitudes, norms, and behaviors as a matter of course.

Early in life I learned that each individual perceives the world around him or her often in quite different ways than everybody else does. Because I understood at a young age that people experienced the world differently, I accepted that what was the norm in my context could be strange to someone else. Having this ability is a challenge, yet a gift all at once. I have always been naturally drawn towards global literature, books that are set in different cultures, and more importantly, books that present different perspectives on the world. Because of my lived experience of perceiving things differently, thinking differently, and being open and accepting of differences, I feel that as a teacher I can challenge my learners in ways in which they may not been challenged before and enrich their learning experience.

Understanding and accepting differences can be strenuous for students being brought up in predominantly mono-cultural environments. Our school is in a predominantly white neighborhood but with a mix of different ethnicities, including African American, Arab, Chinese, Korean, Indian and Pakistani. For example, in this class, one of the three sections of fifth grade that I teach, I have 20 students, 9 boys and 11 girls. Two students are Latino, one is Indian, one Filipino, and one African American. Only about 5% of our overall student population is on free or reduced lunch. In this reflective piece, I explore why I think exposure to global literature is a powerful way in which students can gain direction and personal insight for their futures in a global world. Learning about other cultures and becoming able to explore new ideas and prospects make options available to us that would not exist otherwise. This is why I believe it is so important for students to have a deeper global awareness and understanding of other cultures. As I explore below, I use global literature texts that appeal to students’ interests and abilities to help them step beyond stereotypes and generalizations and towards deeper understandings of differences.

Learners as Travelers: The Students

As fourth graders, my students engage in a comprehensive study of immigration, which is central to the identity of the U.S. as a nation, and to the history of its citizens. The students are excited as they learn about their ancestors’ native countries of origin, and discover their own connections to the immigrant experience and to a wider world. Studying immigration as part of their own family story provides an excellent natural context for children to be introduced to the diversity of ethnicities and cultures in the U.S. The children see each other as part of the whole, a nation of people coming together, all sharing the common experience of migration. Celebrating each other’s uniqueness together creates unity and friendship. Students are involved in meaningful, active learning experiences supplemented by personal artifacts, films, historical photographs, and timelines. A big focus of the unit is inquiry and having the students ask questions about people who came to America, when they came and why, where they settled, how they were accepted and how they contributed and took part in American life. The students use self-generated questions to investigate history, asking who, what, when, where, how and why to learn the pieces of a story.

In my fifth grade classroom, I build on this concept of questioning through classroom conversations as a fundamental aspect of a critical literacy curriculum. Through conversation, I want my students to explore multiple perspectives, challenge assumptions, look closely at relationships (especially those involving power) and reflect upon how they can take action for social justice in their world (Dozier, Johnston, & Rogers, 2006; Freire, 2004; Lewison, Flint, & Van Sluys, 2002).

In order to engage the children in what Peter Johnston (2004) has called “dialogic interactions,” I work on teaching them how to listen carefully to each other, ask questions, build on each others’ ideas and disagree with each other in a respectful way. The children control the conversation and I, their teacher, act as the facilitator. These interactions enable the students to consider multiple perspectives as we read global literature that comes from the many countries (India, Vietnam, China, Mexico, South Africa, and Japan to name a few), some of which the students have explored in their fourth grade immigration unit. The students have built quite a bit of background about each other and their various points of origin. Their curiosity about their friends’ cultures and how people live differently is rich ground to start looking at perspective and cultural diversity.

Traveling in New Worlds

During class, my fifth graders and I read a short article by an Indian writer Milan Sandhu from Highlights Magazine titled “Bindi!” Sanjay, an Indian student, had found the article in an issue of the magazine that he was reading and I had made copies for everyone. He explained to us that many women and girls in India wear a bindi or a dot on their foreheads. His mother, aunts and grandmothers wear them. The class was immediately curious and they bombarded Sanjay with questions: “What does the word “bindi” mean?” “How do they make bindis?” “Why do they make/wear bindis?” Poor Sanjay was at a loss because he himself did not know the answers to these questions!

We decided to read the article in our small groups to find out more and then discuss what we had read. Some of our misconceptions were revealed right away. Jennifer wondered: “Do they really carve them on their forehead?” Madison countered: “Why would they do that?” “I bet that would bleed,” commented Samantha. We read on and discovered that bindis are either stickers or marks made on the forehead by tinted powders. My students were intrigued by the fact that bindis can match outfits and be a fashion statement!

The questioning and talk, however, slowly led the class to a deeper exploration of Indian culture and religion as we read about why bindis are worn. Alicia speculated, “Do I have a third eye?” We began to unpack the Hindu belief that there is an inner core within each of us that is the seat of concealed wisdom. It is the center point wherein all experience is gathered in total concentration; it is our third eye and that spot is marked on the forehead by the bindi. “Wow! Is that where my soul is then?” exclaimed Eric. A debate ensued about what the soul might be and whether it is the same as or different from the third eye.

There are no answers, but we reached a level of understanding that went beyond just knowing facts. John wondered, “What else do they believe?” We brainstormed how we can discover more about the beliefs and peoples of the Indian Subcontinent. The students were noticing the multiple levels at which some of their ideas and beliefs are the same as what they read in the article, and yet so different, and how fundamental and key ideas are interpreted in different ways in the world.

There were rich side conversations exploring gender roles, customs, science and medicine through questions ranging from: “Can anyone wear a bindi?” (Tara) “Why do they/did they have the tradition of applying blood to the forehead?” (Julian) “How is it cooling?” (Mick) The talk was a process of discovery as the students evolved in their thinking about something that appeared to be peculiar and exotic to them at first, but is in fact the norm for people in its cultural context. We ended the class with Sanjay promising to bring us some bindis to try on and the students excitedly discussing what each of them was going to research online about India.

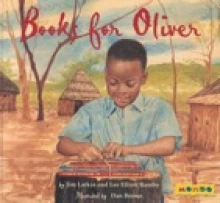

My fifth graders were engaged in conversations around Books for Oliver that I had finished reading aloud to the class. The class had selected the book because it is set in Africa and they love the stories that I tell them about my childhood and life in Africa. The book is about Oliver, who lives with his family in the highlands of Kenya. Oliver is excited about school and the new school year, but he and his parents worry about how they will afford to buy his textbooks.

The students’ written reflections following our discussions revealed a wide range of responses. They were clearly moved by the story and had a strong sense of empathy for Oliver. Their writing explored the situation, behavior and relationships of a child who was just like them, but so different in so many ways. Ashanti wrote, “I felt bad when he saw the other kids with books. Once I felt bad when I didn’t have something and everybody else had it.”

The students identified with Oliver as a student, and with his hopes and desires. They felt the pain of his challenge. Margaret reflected, “If I was Oliver, I would feel scared and embarrassed. I would be scared because I did not have my books and everyone else would. I would feel embarrassed because I could not be able to learn with the other students….I got the same reaction Oliver did when he got books! I was happy, glad, and excited that he got new books!” Brenda empathized with Oliver’s determination, writing: “You can tell that Oliver really wants to learn. He wants to succeed and have a bright future, and he won’t give up until he is in school learning.”

The students’ questions and comments expanded their ways of thinking and understanding. By seeing and trying to come to grips with a new and different experience, they explored what they know or have heard about other people and other countries. Max, for example, wrote: “The first feeling I had was a little happy for Oliver because he had such a good (yet simple) life, because when I think of “People in Africa” I think poor people with dirt huts, small and cramped. The next feeling I had was sad that he didn’t have any books for school.”

The students also puzzled over the differences in their own experiences of schooling and learning and Oliver’s. Harris reflected: They love school. It is like winning the lottery for them and kids in America usually don’t want to go to school. Which is really amazing!” Michael was thinking along similar lines: “What makes me upset is that sometimes kids in the U.S. don’t want to go to school but have to because it is the law.”

Just like in our discussion, the written reflections showed the students’ thinking taking a turn towards social justice as the students began to tackle the issue of poverty and the ethics and morality of having so much when so many others are deprived. Catherine reasoned, “His life is hard. He is poor and they should get money because they are hard working.” The students felt the inter-relatedness of the human experiences and were challenged to seriously examine themselves and the contrast in their situations and environments. Violet was moved by the difference: “I feel very sad about how their life is there and how lucky we are to live in a place like this.” Eric reflected on some harsh realities: “I honestly don’t think it is fair that in America we don’t need to pay for our school books but in countries like Africa a lot of other people can’t even afford one single book.” Sanjay pondered upon the future as well as the present: “I hope Oliver gets a good job so his kids can have a really good life, because I bet his kid will be just like him.” Katy drew a powerful lesson for herself and all of us from the story: “So maybe next time you go to the store and want something, think about kids in different countries and remember what situation they could be in.”

Seeing with New Eyes

Sometimes we think that young children have limited capacity to think about complex situations, but our vignettes show that creating the spaces to read global literature and nonfiction texts about the wider world, and then taking the time to talk about meaningful issues can allow students to become more powerful and more purposeful, more informed and intelligent, more aware and more free in their thinking. I find my students very quick to identify and to express concerns about their perceptions of unfairness, as well as their empathy for others. My own passion for global literature and my way of thinking and being is an interesting dynamic in the classroom because I am always making the unfamiliar familiar to them by being who I am. At the same time, by bringing the world to my students through offering them opportunities to read global texts, I am always challenging them in their thinking. We travel the world through our reading, and as we do, we look at it together with new eyes and new understandings. To do this, I need to build community and trust, and while that takes time, the end result is that my students feel secure and encouraged to actively seek out views, norms and situations that are different from their own. They are open to exploring them, both to try and truly understand their own selves, as well as to see the humanity of others, which to me is truly the essence of global thinking.

References

Dozier, C., Johnston, P., & Rogers, R. (2006). Critical literacy/critical teaching: Preparing responsive teachers. New York: Teachers College Press.

Freire, P. (2004). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum.

Johnston, P (2004). Choice words: How our language affects children's learning. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Larkin, J. & Rambo, E. (2007). Books for Oliver. New York: Mondo.

Lewison, M., Flint, A. S., & Van Sluys, K. (2002). Taking on critical literacy: The journey of newcomers. Language Arts, 79 (5), 382-392.

Proust, M. (1913/1982). Remembrance of things past. New York: Vintage Press.

Sandhu. M. (2005). Bindi! Highlights for Children Magazine, 60 (6), 8.

Simeen Tabatabai teaches reading to fifth graders at Southgate Elementary School in the North Colonie School District in Colonie, New York.