Keeping Literature Alive

By Vera Zinnel

The 2012-2013 school year portended to be a challenging one; it would be the first year that my district was going to follow the new Common Core State Standards (CCSS) with earnest. We had already been trained with the new math standards and provided with a new curriculum. At the staff development meeting days prior to the opening of the school year, we were presented with the new CCSS for English Language Arts (ELA). The assumption that we made was that implementing these new standards would be up to each teacher. Not only would we be implementing the new standards, but teacher evaluations were also changing. I sat in the cafeteria listening to what standards I would be judged by and I felt confident that in my 24th year of teaching I had this!

In late September the third, fourth, and fifth grade teachers were scheduled to attend a district meeting for staff development. We were presented with large binders containing our new ELA curriculum that would help us meet the CCSS. What struck me when I opened the massive binder was the word draft printed across all the pages. Why were we being asked to implement a program that was not even finalized? As I read through the binder, I realized the first module dealt with the constitution written by the Iroquois people of New York State. It was very non-fiction heavy. The program was very scripted and the lessons were supposed to take 45 minutes to an hour. I went back to my classroom and put the binder away on my shelf.

I felt that what I was doing in my classroom already was as rigorous as this new curriculum. No one had said we “had to” do this curriculum and it did say draft across all the pages; surely we were not to use a program that was in its draft form. What, I wondered, would I have to give up to fit this curriculum in? I told my class at the beginning of the year that we would be reading many books and learning about how history is written. I told them we would become detectives as we read from different sources in an effort to determine what we think is the truth and what is not. My class was up and running with a routine and our guided reading groups were going well. The class was engaged and starting to read rigorous books. Many of the books that I had chosen fit the criteria of the CCSS but were not on the text exemplar list. I was using the criteria suggested by the CCSS of using Lexile level, guided reading level, and purpose for reading. I felt confident that I was adhering to and incorporating the new standards.

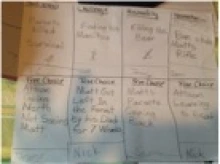

In October, one of my colleagues started the new curriculum. She said she was going to use it as her ELA and Social Studies programs. I had a conversation with her about how she was fitting it all in. She told me that she did not do guided reading groups and that was how she was able to fit it in. I had five guided reading groups going in my class and I was determined not to stop. Math and Science still had to be taught, and combining ELA and Social Studies was not going to help either. With five guided groups meeting for 15 to 20 minutes four days a week, the time was not there.

Shortly after our return to school, which had been interrupted by Super Storm Sandy, I met with my Assistant Principal to discuss my goals for the year. It was then that he asked what I thought of the new curriculum. I told him that I was not using it and preferred what I was doing, explaining that I had no time in my schedule to fit it in. He explained to me that it was expected that I use this curriculum. The district felt that since the program was endorsed by the state and available on the website EngageNY, using it would provide our students with the best preparation for the new state tests they would have to take. I asked where exactly I would be fitting this in. After looking at my schedule, he told me I would have to stop my guided reading groups. I was stunned! We had a long discussion in which I cited various studies and books extolling the benefits of guided reading. Hadn’t the district just trained me for the past three years in balanced literacy, the bulk of which dealt with guided reading groups? He shrugged his shoulders and told me this was what would be happening from now on. I guess it was time to dust off the binder.

I logged on to EngageNY and discovered that draft had been removed from the pages of module 1. I took the binder home and tried to figure out how I would use this program and remain committed to my ideals of what was pedagogically and instructionally sound for my students. I dove in with my class and we started our inquiry of the Iroquois Constitution.

When I finally came to terms with implementing this curriculum, I realized that, like anything else, I did not have to stick with the script. I adjusted and tweaked the program to fit the needs of my class. Something was missing, however. The ELA curriculum was non-fiction heavy with only one novel included in module 2. The children were enjoying learning about the Iroquois, but I was concerned about the lack of fiction and I was missing the talk that surrounded reading a good fiction book with my class. I am committed to selecting books that go beyond the CCSS text exemplar list to include global literature and keeping literature alive. I view Appendix B for Text Exemplars as a guideline of sorts. There are so many wonderful, quality books not on the list that all children should have the opportunity to read.

I decided that I could find 15 to 20 minutes three days per week to read a book with the class and selected The Sign of the Beaver by Elisabeth George Speare. It has a high Lexile level, which implies that there will be plenty of opportunity to introduce some enriching vocabulary words. The guided reading level is listed as appropriate for 5th grade. There is also some controversy surrounding the book; some feel that the book does not portray Native Americans in a positive light. The dialogue used for the Native American characters is thought to be old Hollywood stereotypes. Perfect, I thought. We can read this book and read it critically by talking about why some people find the book objectionable and learn some new vocabulary words. In addition, The Sign of the Beaver fit nicely into the new curriculum.

The class enjoyed the book right from the start. It was a difficult text for some in the class, but together we read it. The talk was wonderful; “How could the father leave his son alone in the woods?” “Why is Attean so mean to Matt?” We were up and running. Every day, my class would ask, “Are we going to read The Sign of the Beaver today?” They made connections to what we were learning about the Iroquois to the novel. They discovered that Native Americans did not only live in upstate New York and on Long Island, but all over the United States.

Through critical conversations, we addressed some the controversies surrounding The Sign of the Beaver, particularly the issue of stereotypes. Imbedded in the story is the idea that “Indians” were seen as savages. This is addressed in the text where the main characters read about Robinson Crusoe’s treatment and attitude toward Friday. Because we had been studying the Iroquois Constitution, some students were able to make the connection that “savages” would not have created a whole system of government. One student was able to see that the main native character, Attean, had his own prejudices regarding white men. Another area of controversy is the portrayal of the way that Saknis, the grandfather and native leader, speaks English. The speech patterns are reminiscent of the stereotypes perpetuated in Old Hollywood films. This was not an easy bias for the students to recognize; however, we did discuss preconceived notions about Native Americans. As a part of the required curriculum, we read the book Eagle Song by Joseph Bruchac. By pairing this text with Spear’s The Sign of the Beaver, the class was able to make the connection that just as the main character in Eagle Song was unfairly characterized as living in a teepee and was being called Chief by others, sometimes in books and films, Native Americans are reduced to stereotypical characteristics.

Because the class was really enjoying our reading of The Sign of the Beaver, I found that we were spending more time on it and that I was incorporating more resources into our literature unit. While searching on the social website Pinterest, I found many great ideas for whole class reading and implemented several of them. We also discovered that there is a movie based on the book, which we viewed. We found the movie to be very different from the book. This sparked a wonderful conversation; there were those who liked the new additions present in the movie, and then there were the purists who were indignant that the book was changed. I enjoyed listening to their ideas and thoughts. More importantly, through these literary experiences I believe that I was keeping literature alive in my classroom.

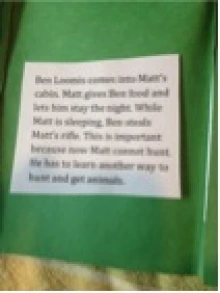

Once we finished reading the book, the class worked in small groups on a lift-a-flap book project. For the project, I asked my students to pick out the scenes they thought best portrayed each character; one of the book’s themes; and showed how the characters changed. For each scene, I instructed them to write a paragraph explaining why they selected the scene and how the scene fit the criteria. For the flaps, they drew pictures of the scenes they selected. They enjoyed working on this project. The discussions that took place within each group, as they debated which scenes to portray, were priceless.

At the end of the year, reading that book and the other four books that followed, were listed as some of the students’ highlights of their year. Two boys expressed an interest in reading Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, which was featured prominently in The Sign of the Beaver. I felt all my students ended the year with a good sense of story. They became more thoughtful readers and were aware of theme. I felt successful in that I was able to keep literature and the novel, a vital part of schooling, alive in my classroom.

References

Bruchac, J. (1997). Eagle song. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Spear, E. G. (1983). Sign of the beaver. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Vera Zinnel is a classroom teacher in an economically, culturally, and linguistically diverse suburban school district in Long Island. Vera is also a doctoral student in Literacy Studies at Hofstra University.

WOW Stories, Volume IV, Issue 6 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/storiesiv7.