Developing a Literacy Curriculum with Global Literature

By Prisca Martens and Ray Martens

Our Vail Global Literacy Community is a school-based group at Creation School in Vail, Arizona, located southeast of Tucson in the heart of the Sonoran Desert. Creation School is a Lutheran school that serves a total of about 60 students from ages two through third grade (second and third grades were new in 2020-2021). About 50% of the students are of Latinx heritage and 50% European American and Asian. While a few teachers and students speak Spanish, English is the primary language used.

Creation School provides a Christ-centered environment that nurtures children's faith, strengthens families, and invites children to explore and discover their world through rich learning experiences. The outdoor classroom space includes chickens, a butterfly garden, and a natural playscape (i.e., tires, crates, boards, natural elements), all of which extend children's opportunities to inquire about their world, learn, and grow. 2020-2021 was Creation's eighth year.

We (Prisca and Ray) are retired teachers/professors, living in Vail, Arizona, who enjoy spending time with the teachers and students at Creation. In this vignette we introduce our 2020-2021 Vail Global Literacy Community and our goals for the year. We then discuss our work in the classrooms. Our group included teachers from preschool through third grade, but the two of us were only able to directly work in classrooms with students in the elementary school (kindergarten through third grade) on Creation's campus and not with the younger students in another building, due to the school's Covid-19 protocols.

Our Vail Global Literacy Community Study Group

Our Vail Global Literacy Community Study Group had 11 members: Lacey Elisea (kindergarten teacher), Jane Metzger (inclusion specialist/kindergarten teaching assistant), Meghann Kjolsrud (1st-3rd grade teacher), Samantha Zedric (1st-3rd grade teaching assistant), Cassandra Sutherland (K-3rd grade physical education/art teacher), Kelsey Nowacki (pre-kindergarten teacher), Abbey Unes (pre-kindergarten teacher), Jessica Berry (preschool teacher), Jennifer Hook (school administrator/prekindergarten teacher), Ray Martens (facilitator), and Prisca Martens (facilitator).

Our monthly meetings were always lively and energetic with rich conversations about our teaching and the students in our classrooms. The meetings always began with teachers sharing about happenings in their classrooms (i.e., students' work samples, read-alouds and students' responses, problems/issues teachers raised). Then we discussed a professional reading, planned for the next few weeks of school, and set our next meeting date and assignment. Our professional readings included vignettes previously published in WOW Stories, Kathy Short's (2009) article "Critically Reading the Word and the World: Building Intercultural Understanding Through Literature", and Lester Laminack and Katie Kelly's (2019) book Reading to Make a Difference: Using Literature to Help Students Speak Freely, Think Deeply, and Take Action.

The goals of our Vail Global Literacy Community in 2020-2021 were to continue to develop the global literature curriculum organized around a "Curriculum that is Intercultural" (Short, 2016) that we started in 2019-2020; and to continue developing writing and art experiences that invite students to explore global literature and deepen their intercultural understandings, as well as create and share their own stories. These goals were the primary focus of our work in the classrooms.

Prisca and Ray in the Classrooms

We were in the kindergarten and 1st-3rd classrooms two to three mornings a week to read and discuss global literature with a focus on developing students' intercultural understandings and supporting students' reading, writing, and art in Storying Studio.

A Curriculum that is Intercultural

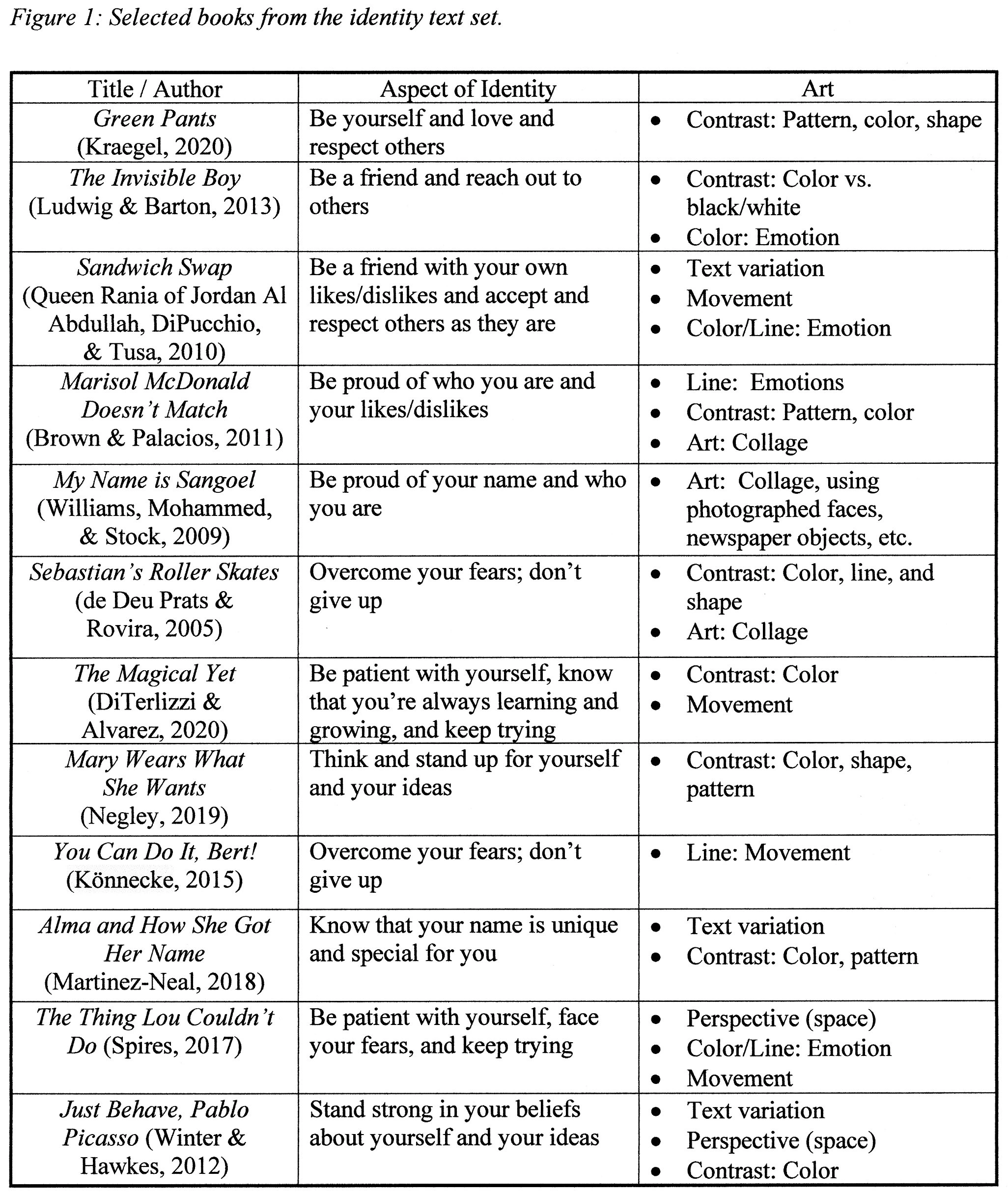

Our first major focus with global literature was identity and helping students understand, accept, and know themselves as unique cultural beings. That understanding is critical to their accepting and valuing others (Banks, 2004). By appreciating the significance of culture in their own lives, students come to appreciate and respect its significance in the lives of others, marking the beginning of intercultural understandings (Pattnaik, 2003; Short, 2009).The books we read related to identity considered such aspects as family, emotions, confidence, fears, standing up for yourself and for others, etc. (see Figure 1 for a sampling).

Figure one. Selected books from the identity text set

Experiences we provided for students included indicating where each child's family originated on a world map, learning how each child's parents selected children's names, and keeping journals with responses and connections to books we read. Several of the teachers' vignettes in this issue include these and/or other examples of how they helped their students think about their personal identities and consider who they are as cultural beings. Vignettes that particularly explore this are "Sacred Stories as Windows and Mirrors: A Pre-Kindergarten Class Reflection" by Jennifer Hook and Abbey Unes; and "A Global Literature Study of Identity and Kindness in Pre-Kindergarten and Preschool Classrooms" by Kelsey Nowacki and Jessica Berry.

When we (Prisca and Ray) were not at school, teachers read/discussed global literature, provided materials and opportunities for students to reflect in journals and write/illustrate their own stories, and organized their own inquiry studies. In "The Hohokam People Project: Learning Through 'Windows' and 'Mirrors' in a Cross-Cultural Study," Meghan Kjolsrud shares a project that she developed with 1st-3rd graders on the ancient Hohokam Indigenous peoples who once lived in the Sonoran Desert.

Our other major focus with global literature was knowing, appreciating, and respecting cultures differing from our own. We did cross-cultural studies on Mexico and China. Each of these studies involved learning something about the cultures, languages, families, geography, beliefs, and a particularly important celebration. Lacey Elisea, Jane Metzger, and Cassandra Sutherland provide highlights of these cross-cultural studies with their kindergarten students in their vignette, "Using Global Literature as 'Bridges' to Understand Ourselves and Other Cultures."

Our foci on cultural identity challenged students to think about themselves in relation to their families and their personal places in that history; their friends, fears, hopes, and dreams; and unique qualities that make them special. The cross-cultural studies built on and extended this focus on children's identities by inviting students to think about how they relate to others in the world, particularly in Mexico and China. Seeing similarities and differences between themselves and children in other parts of the world encouraged their beginning awareness and respect for different perspectives as well as the common human experiences everyone shares (Short, 2009). As Short states, "Not only can studies provide a window on a culture, but they can also encourage insights into students' cultural identities. Students come to deeper understandings about their own cultures and perspectives when they encounter alternative possibilities for thinking about the world" (p. 6).

Storying Studio

Storying Studio encompasses our readings and discussions of global literature and the story concepts, meanings, and connections students make but, in addition, specifically focuses on the ways the author and artist create meanings in a picturebook (Martens & Martens, 2018; Martens et al., 2018). It is structured similarly to writing workshop with mini-lessons and time for students to explore ideas, write, and create art. It deliberately celebrates diverse ways of making meaning, particularly through art and written language.

During Storying Studio, when appropriate after reading and discussing a picturebook, we invited students to examine aspects of the author's craft (i.e., story structure, character) and how the artist of the book created meaning in the art (i.e., use of lines, shapes, color; see Figure 1) and/or how the book was constructed (i.e., fold-out pages, flip books). We also provided opportunities for students to write and illustrate their own stories. Students decided whether to use information we discussed in mini-lessons and also selected the topics and format for their books.

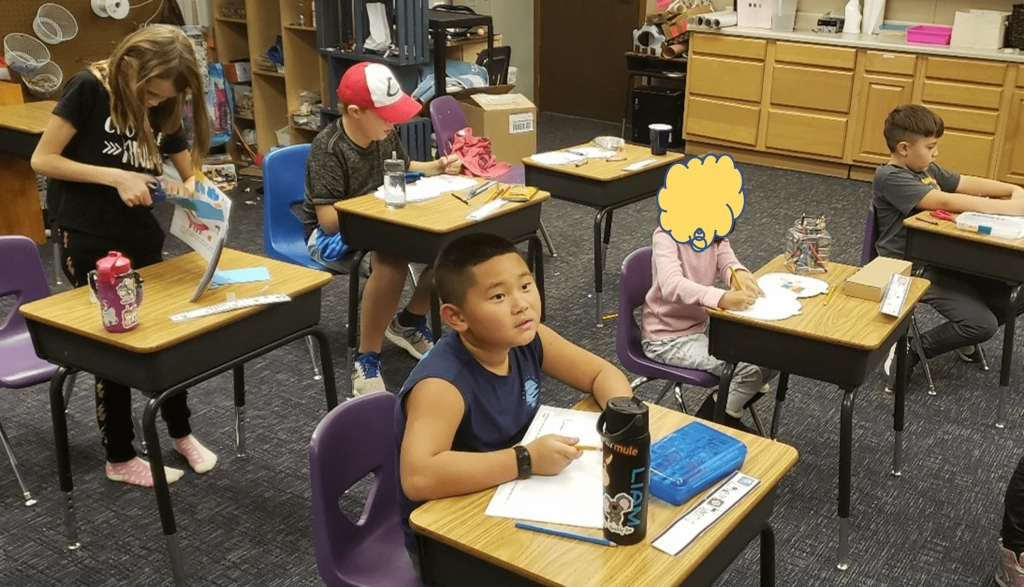

For example, in the fall we found inexpensive but good quality blank books in the shape of a pumpkin or with fall leaves on the cover at a local Target store. We showed 1st-3rd grade students the covers, they chose one, and drafted stories on other paper. Their stories focused on topics such as Halloween, making friends, and zombies. After editing their stories, Prisca typed the texts and we helped students glue the text onto the appropriate pages. Then students illustrated their books. Ben, for example, chose the fall leaves cover but could not decide between topic possibilities so wrote two shorter stories, one about boy/girl relationships and the other about his dog. He made a flip book; one story started in the 'front' and he flipped the book upside down so the back was now the front for the other story. The two stories met in the center of the book. Figure 2 shows some of the students working on their books.

Figure 2. 1st-3rd grade students working on books they had written.

In kindergarten we provided blank books we stapled together for the students to write/illustrate their stories. To provide additional support for them as writers, we also wrote several language experience stories as a class, with students dictating the story from an experience we shared. One such story was after our school International Dot Day celebration (based on The Dot by Peter Reynolds, 2003). The story dictated by students explained that we read The Dot, how they made dots, etc. We copied their story into books (in the shape of a dot) for each student to read and illustrate.

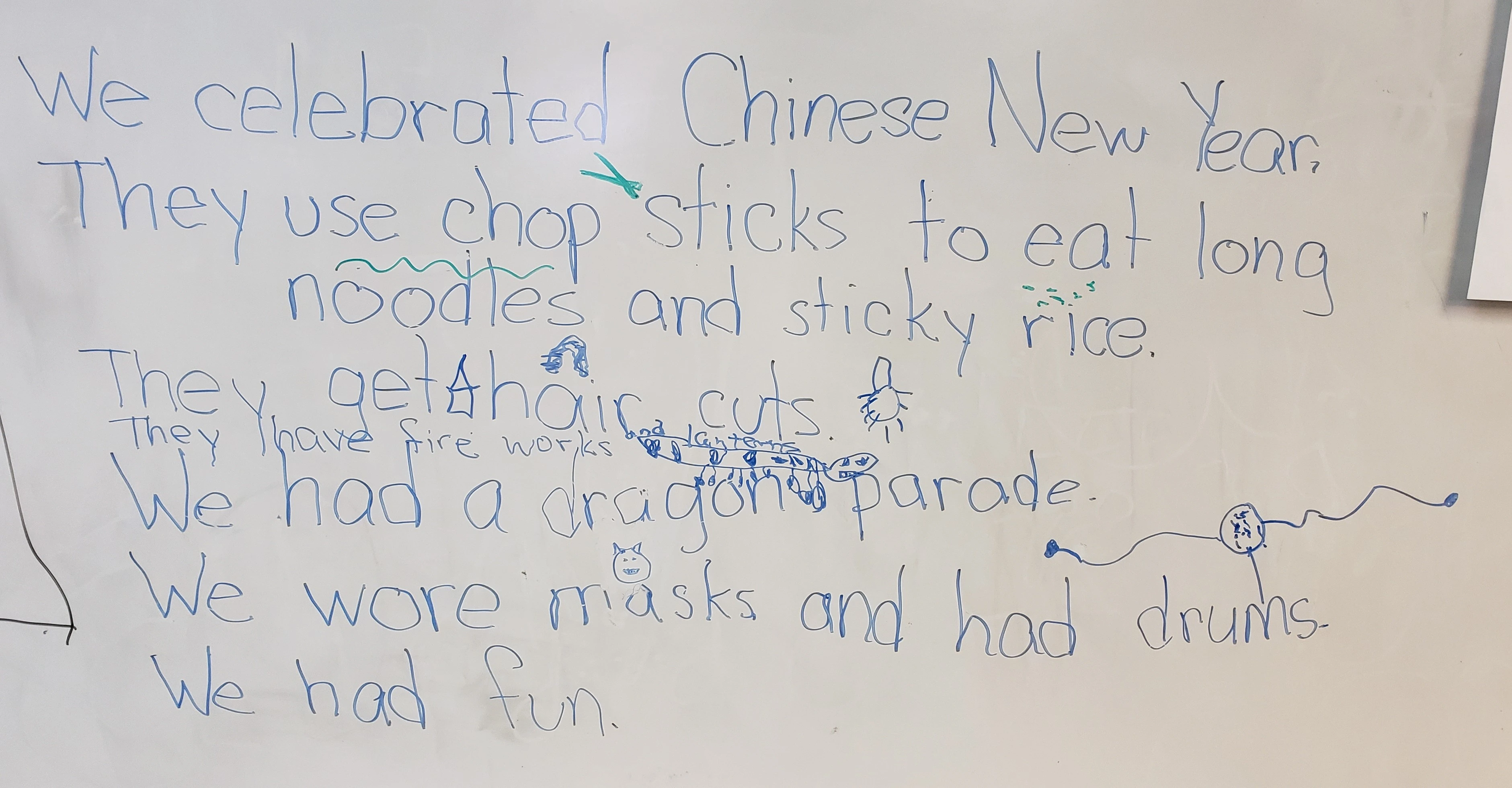

Kindergartners also dictated a language experience story about our Chinese New Year celebration. The first part of their story described how Chinese people prepare for the celebration and the second part told about our school celebration (see Figure 3). After students read the story, some came up to draw rebus pictures above particular words to offer support when they read the story again.

Figure 3. Story about Chinese New Year the kindergarten student dictated with rebus pictures.

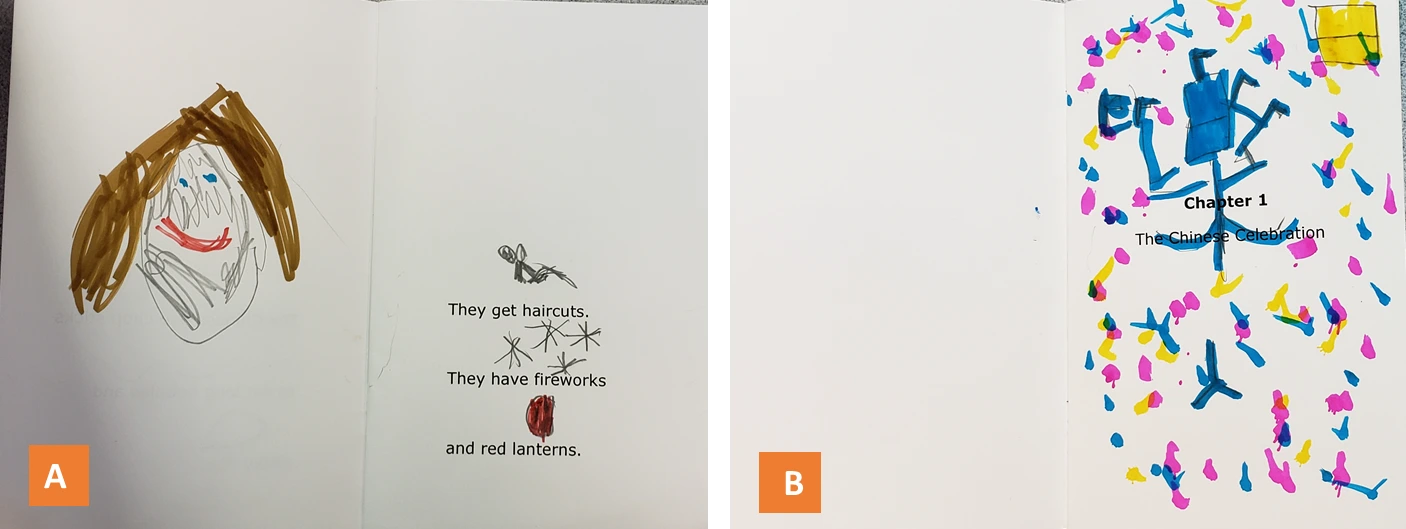

When Prisca typed the story and made it into a book for each student, she decided to turn it into a chapter book with the first chapter on Chinese preparations for the celebration and the second about our celebration. Students were thrilled to have a chapter book! They illustrated their pages and added rebus pictures for particular words (see Figure 4-A). Some students also decided to add Chinese characters to their books (see Figure 4-B).

Figure 4. Student’s illustrated pages including rebus pictures for selected text (A) and Chinese character student added on the page (B).

Students loved reading and rereading their books and were excited to take them home to share with their families. The books were a rich reflection and celebration of their learning about Chinese New Year as well as a strong support for their literacy development. For details of the full study of China and the Chinese New Year celebration see Lacey Elisea, Jane Metzger, and Cassandra Sutherland's vignette "Using Global Literature as 'Bridges' to Understand Ourselves and Other Cultures" in this issue.

Closing Thoughts

We have consistently found that the richness of global literature, whether the focus is on knowing oneself and personal identity, another culture, or some other topic, captivates students' interests, generates deep authentic discussions, stimulates genuine personal connections, and inspires students' imaginations and creativity. In turn, students are motivated to write and illustrate their own stories, sparking their continued growth as readers and writers. Our journey towards developing a literacy curriculum this is intercultural with reading, writing, and art experiences in Storying Studio has been productive and exciting and one we look forward to continuing in the years to come.

References

Banks, J. (2004). Teaching for social justice, diversity, and citizenship in a global world. The Educational Forum, 68(4), 296-305.

Laminack, L., & Kelly, K. (2019). Reading to make a difference: Using literature to help students speak freely, think deeply, and take action. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Martens, P., & Martens, R. (2018). Enhancing experiences with global picturebooks by learning the language of art. WOW Stories, VI(1). https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/wow-stories-volume-vi-issue-1/3.

Martens, P., Martens, R., Doyle, M., Loomis, J., Fuhrman, L., Stout, R., & Soper, E. (2018). Painting writing, writing painting: Thinking, "seeing," and problem-solving through story. The Reading Teacher, 71(6), 669-679.

Pattnaik, J. (2003). Learning about the "other": Building a case for intercultural understanding among minority children. Childhood Education, 79(4), 204-211.

Reynolds, P. (2003). The dot. Somerville, MA: Candlewick.

Short, K. (2009). Critically reading the word and the world: Building intercultural understanding through literature. Bookbird: A Journal of International Children's Literature, 47(2), 1-10.

Short, K. (2016). A curriculum that is intercultural. In K. Short, D. Day, & J. Schroeder (Eds.), Teaching globally: Reading the world through literature (pp. 3-24). Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Prisca Martens is Professor Emerita, Towson University, Towson, Maryland, where she taught literacy courses. She is retired and living in Vail, Arizona.

Ray Martens is Professor Emeritus, Towson University, Towson, Maryland, where he taught art education courses. He is retired and living in Vail, Arizona.

© 2021 by Prisca Martens and Ray Martens

WOW Stories, Volume IX, Issue 2 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work by Prisca Martens and Ray Martens at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/volume-ix-issue-2/3.

WOW stories: connections from the classroom

ISSN 2577-0551