Using Global Literature as Bridges to Understand Ourselves and Other Cultures

By Lacey Elisea, Jane Metzger, and Cassandra Sutherland

We are educators at Creation School, a Lutheran school located in Vail, Arizona, approximately 20 miles southeast of Tucson. Lacey Elisea has a degree in early childhood and is currently Creation's kindergarten teacher. Jane Metzger has an early childhood and special education background and helps Lacey in kindergarten. Cassandra Sutherland has an engineering background and currently teaches physical education and art for kindergarten-third grades.

The 2020-2021 school year began a couple of weeks late and with a lot of uncertainty about what the year would hold due to Covid-19. Our kindergarten had 14 students (seven boys, seven girls) in class and three virtual students at home, who eventually joined us in our classroom. The students were mainly from European backgrounds with some from Latin American, African, and Asian families.

We were members of our Vail Global Literacy Community where we read Reading to Make a Difference: Using Literature to Help Students Speak Freely, Think Deeply, and Take Action by Lester Laminack and Katie Kelly (2019). We were particularly struck by Laminack and Kelly's concept of "books as bridges" as a compliment to the books as "windows/mirrors" (Bishop, 1990). Laminack and Kelly (2019) state that when books are used as bridges, they "offer the reader an opportunity to connect to distant places, different views, unique people and new experiences" (p. iii).

In this vignette we share how we integrated books as bridges into our curriculum in cross-cultural studies of Mexico and China to help the students develop a deeper understanding of themselves and the world around them. We begin with a brief look at how we first helped students think about their own identities as cultural beings.

Books as Bridges

Exploring Personal Cultural Identities

Figure 1. World map indicating where students’ ancestors originated.

To begin the year, we wanted students to understand their own identities and who they were as cultural beings prior to moving into cross-cultural studies. Kathy Short (2009) argues, "Interculturalism does not begin with the ability to consider other points of view but with the realization that you have a point of view" (p. 3). The books we read related to identity and our discussions focused on understanding ourselves as individuals and on who we are as members of our families, classroom, and community. For example, we read All the Ways to Be Smart (Bell & Colpoys, 2019) to celebrate the talents that each student brings to the world. The book highlights a wide range of ways people are smart (not just grades and test scores), from building boats out of boxes to painting by using one's imagination. The students enjoyed making their own books about how they were smart.

As students' understandings of their personal identities developed, we expanded to look at their families and ancestry. We read My Name is Elizabeth! (Dunklee & Forsythe, 2011) which allowed us to discover how special names are. Students gathered information from their parents and then shared in class what their names meant and how their parents chose their names. Students also found out where their ancestors originated and we marked the places on a world map (see Figure 1). Students began to realize that their family, cultural background and personal experiences impact who they are, how they think, and their actions. For a list of other books we read related to identity see Figure 1 in Martens and Martens' vignette "Developing a Literacy Curriculum with Global Literature" in this issue.

Exploring Mexico through Literature, Art, and Drama

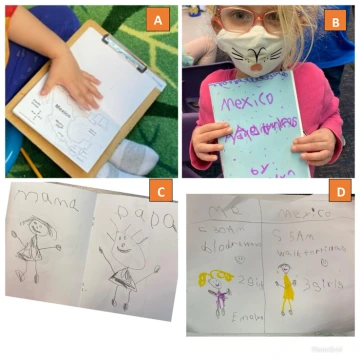

Figure 2. Pages from Emelyn’s Mexico journal: Her world map (A); her title “Mexico

Adventures” (B); Mexican parents as “mama” and “papa” (C); t-chart comparing and contrasting herself and children in Mexico (D).

After our study of the students' individual identities, we did a cross-cultural study of Mexico. Only three students (Ethan, Dean, Noel) had cultural ties to Mexico but most were aware of Mexican culture due to our community's proximity to Mexico. Our study focused on Mexican culture, food, art, and history. We read books like Let's Explore Mexico (Moon, 2017) and If You Were Me and Lived in Mexico (Roman, 2013) which provided an overview and highlights of the country. This led to the students working on a map to understand Mexico's geographical features and starting a journal to make notes about their learning.

Emelyn titled her journal "Mexico Adventures" and noted how in Mexico children had a mom and dad like her but called them "mama" and "papa" (see Figure 2-A). After watching a short clip from Marc Kosak's 2020 documentary about how children get to school in Mexico, Emelyn compared herself to the children in the documentary. She made a t-chart about her observations, comparing wake up times, breakfast, siblings, and emotions (see Figure 2-B). She drew a happy face on the left side labeled "Me" and a sad face on the right side labeled "Mexico". She said, "I put a sad face because if I had to walk at 5AM, I would not be happy." Through these experiences, Emelyn and her classmates took a deeper look at culture and realized not everyone in the world lives like they do. They began to understand that children in other parts of the world are similar to them in some ways but also different. They learned to identify their own cultures as well as to distinguish and value cultural differences. Emelyn and her classmates crossed a bridge to experience life in Mexico and deepen their understanding of their own identities.

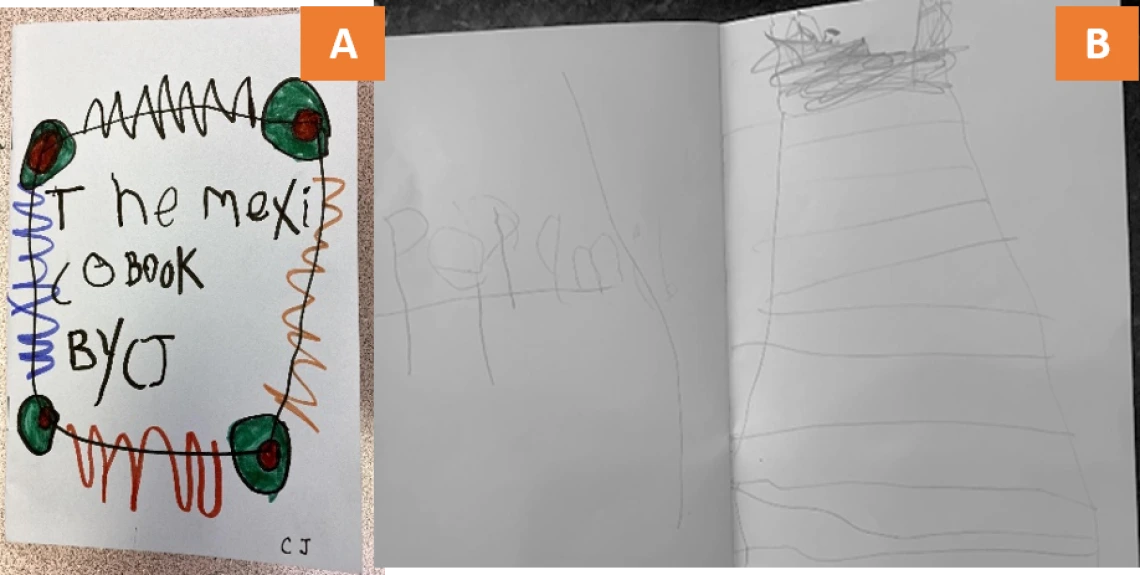

While some students focused on families in their Mexico journals, others focused on landmarks, symbols and colors. C.J. titled his book "The Mexico Book" and explained he tried to use the colors of the Mexican flag to decorate his title (see Figure 3-A). Dean focused on the pyramids located in Mexico and the difference in these pyramids because they do not have a point at the top (see Figure 3-B). His detailed drawings show the steps up and the flat top. The journals revealed how each student connected with different concepts and experiences. The students used their past personal experiences and interests to make new connections and discoveries.

Figure 3. C.J.’s (A) and Dean’s (B) Mexico journals.

Las Posadas. When our church asked Creation School to organize the Christmas Eve service, we decided to create it around Las Posadas, the Mexican celebration/reenactment of Joseph and Mary going house-to-house looking for housing in Bethlehem prior to Jesus' birth. The people on the procession are told that the Posadas (The Inns) do not have any room until they reach a manger and are allowed to stay, just as Mary and Joseph were. To prepare, our class began researching Las Posadas and its meaning. We hoped the students would get past the "tourist perspective" and begin to understand the cultural relevance of the event (Short, 2009, p. 1). Through literature like Las Posadas (Hoyt-Goldsmith & Migdale, 1999) and The Night of Las Posadas (de Paola, 2001) we learned that the Posadas are an important tradition complete with prayer, music, and food.

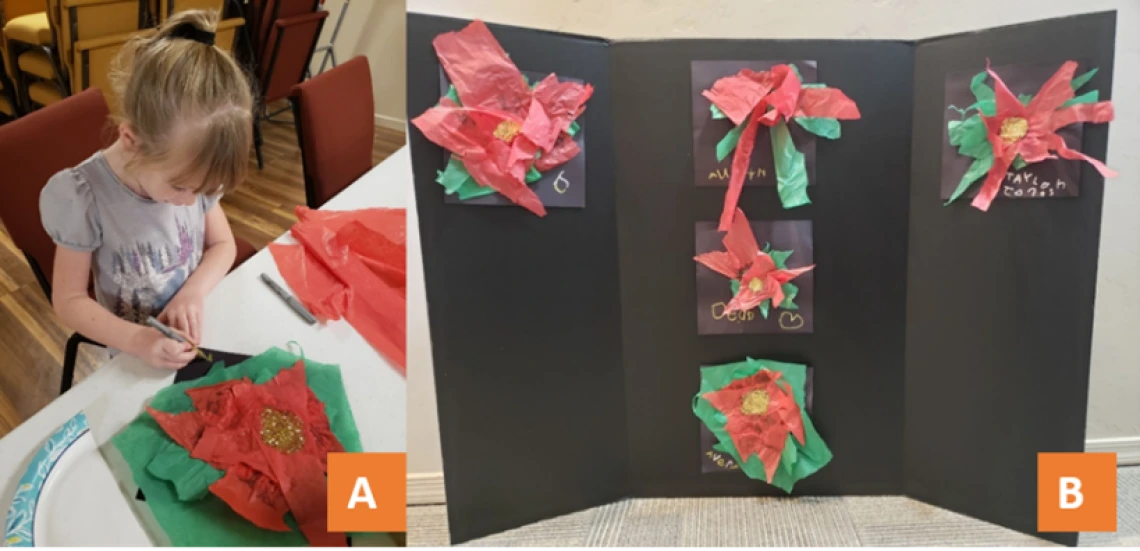

Students also learned about poinsettias in art class by reading The Legend of the Poinsettia (de Paola, 1997). This story of a young Mexican girl's first Posadas added to the students' background knowledge and understanding of Mexican culture (Laminack & Kelly, 2019). In art class, after reading the story, students made poinsettias out of tissue paper, glue, and glitter (see Figure 4-A). First, students examined the illustrations in the book to spark their imaginations of new possibilities for their poinsettias (Ray, 2010). Though the students all used the same mixed media, their poinsettias showed the diversity of their ideas and imaginations. The poinsettias were displayed for the families at the Posada celebration at the school (see Figure 4-B).

Figure 4. Making poinsettias (A) and completed poinsettias (B) for Las Posadas.

During our research, we learned that after the procession, families/communities have parties with piñatas, and we decided to end our Posada that way. Several of the books we read discussed piñatas. While reading, John, age 5, noticed that the piñatas for Posadas were all star-shaped and asked, "Why don't they have character piñatas?" The students were familiar with piñatas from birthday parties but had never seen the traditional star piñata used during Posadas. We researched the "why" and discovered that piñatas used for Las Posadas are usually in the shape of a star with five, seven, or nine points, with each representing a deadly sin. Together we made a traditional star piñata by using cardboard, cones, strips of newspaper and paper mâché (flour and water) (see Figure 5-A). After drying, the students painted and added streamers. They often asked to view images in a book for reference on how these typically looked. On the last day of the celebration, we broke it. Each child took turns swinging and hitting the piñata (see Figure 5-B). We learned a song in Spanish that is sung while hitting a piñata. When the song ended, that student's turn was done as well.

Figure 5. Students working on the star pinata (A) and hitting it as the class watches and sings (B).

The Las Posadas ceremony was open to families and the community. This was a chance for students to perform the traditional Las Posadas song and processions from door to door at school and share a new cultural experience with their families and community. This experience allowed students to link school, home, and community, providing a bridge to share learning and experiences, ask questions and deepen their cultural understandings.

Exploring China and the Chinese Lunar New Year

After our study of Mexico, we wanted to do a cross-cultural study focused in another part of the world, particularly one with a nonalphabetic language to help students appreciate the diversity of languages. Since the past few years our school (and most of our kindergartners) had celebrated the Chinese Lunar New Year (Hoang, 2020) and would again this year, we decided to study China. We explored a range of topics, including Chinese families and customs, Chinese language, China's geography, the Gobi Desert, the Great Wall, panda bears, and attending kindergarten in China.

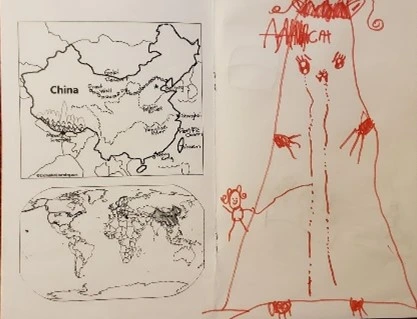

Figure 6. Anna’s China map and drawing of Mt. Everest.

We first pinpointed our location in Vail, Arizona, and the location of China on our world map and on a globe. Books like Welcome to China (Jenner, 2008) introduced China's unique topography, including the Gobi Desert, the Great Wall, rainforests, rivers, oceans and mountainous regions. The students were particularly captivated with Mt. Everest. We compared Mt. Everest to Mt. Lemmon, a local mountain many of them had visited. Students were amazed to learn that Mt. Everest is three times taller than Mt. Lemmon. We drew this proportionally on the white board to emphasize the sizes. In their China journals students found Vail and China on the world map and drew in some of geographic features on their China map. They also drew something important to them from our discussion. Anna's journal with Mt. Everest, including climbers, is in Figure 6.

We also compared and contrasted China's Gobi Desert with Arizona's Sonoran Desert where we live. Since our Sonoran Desert serves as a habitat for many different species of animals and plants, students were interested to learn about those native to the Gobi Desert and add those to their journals. They also enjoyed learning about panda bears and their bamboo diet, which causes them to defecate ("poop") the fibrous bamboo frequently.

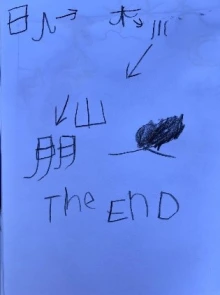

Figure 7. Avery’s story using Chinese characters. She used characters for “sun, person → tree → river → mountain → friend”.

To introduce the non-alphabetic Chinese language, we read The Pet Dragon (Niemann, 2008) which explains Chinese characters. The book provides examples of how and why lines and shapes form the characters and how characters represent ideas and thoughts, which is different than the individual letters in our language. Students practiced writing Chinese in their journals. Avery's story using Chinese characters is in Figure 7. She used arrows to sequence the order of the characters.

After reading Kindergarten Day in China and the USA (Marx & Senis, 2010) we discussed the similarities and differences between attending kindergarten in the two countries. Students noted that while students in China and the USA read, wrote, and ate differently, they all had friends, helped one another, read, wrote/drew, did math, played, and even got haircuts.

Chinese Lunar New Year. With great anticipation, students prepared for Chinese Lunar New Year and the Year of the Ox, which we celebrated on February 12, 2021. We read a number of books, including Chinese New Year (Marx, 2002) and Bringing in the New Year (Lin, 2013). The students loved learning about the lions and dragons that were part of the celebrations. They were surprised that Chinese dragons were considered lucky and good and not scary and dangerous as in most stories with which they were familiar. This helped extend and bridge the students' understandings of their own and Chinese culture. Grace Lin (2016) points out the need for children to "see things from other viewpoints... see outside of themselves". We added a fold-out page to the journals and students drew l-o-n-g snaky dragons as in Lin's book (see Figure 8).

Figure 8. Anna’s foldout dragon.

In Lunar New Year (Eliot & Chau, 2018), we learned why the color red, lights from lanterns, and firecrackers are significant in the celebration. How to Catch a Dragon (Wallace & Elkerton, 2019) added more information about Chinese culture and receiving red envelopes and gold coins during the celebration.

In preparation for our Chinese Lunar New Year celebration, students made red lanterns and drums out of construction paper and noise makers (simulating firecrackers) out of bowls with noise-producing beads and popsicle sticks as handles. They also colored dragon masks to wear. The real highlight, though, was creating the dragon for the grand finale in the parade. We used a big cardboard box for the head and attached a decorated sheet to depict the body and tail of the dragon. Students took turns over several days, using tissue paper for scales, paint, and paper cups with googly eyes, to attend to details to add to the dragon's authenticity. The parade was a success and many parents came to watch (see Figure 9).

Figure 9. Our Chinese Lunar New Year parade.

Following the parade, students enjoyed a Chinese meal, complete with chopsticks, sticky rice, egg rolls, and tea. Students were thrilled to receive a surprise red envelope, containing gold coins for good fortune. The literature we read, our discussions and experiences, and students' reflections in their China journals bridged their understandings and appreciation of culture and further developed their intercultural understandings. After our celebration, students collaborated on a story about Chinese Lunar New Year (See Martens' and Martens' vignette in this issue for information).

Reflection

Through our global literature, discussions, and other experiences, our students crossed bridges and deepened their understandings of themselves and others. We provided them with tools to look deeper and wonder about the world around them. We had not anticipated and were surprised with how bridges also formed with school-family connections and with the community in an unprecedented year full of uncertainty. Students were excited to share their experiences with their families which provided a connection between school and home in a year when parents were not able to participate in the classroom.

Next year we plan to again incorporate global literature and an international curriculum across all subjects. By the end of this year students were asking probing questions about children's daily lives in other countries. This indicated to us their broadening intercultural understandings and their integration of perspectives other than their own which we want to continue.

References

Bishop, R.S. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives, 6(3), ix-xi.

Hoang, V. (2020). Chinese Lunar New Year: A celebration of culture. WOW Stories, VIII(1). https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/volume-viii-issue-1/7.

Laminack, L., & Kelly, K. (2019). Reading to make a difference: Using literature to help students speak freely, think deeply, and take action. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Lin, G. (2016). The windows and mirrors of your child's bookshelf. https://www.youtube.com/embed/_wQ8wiV3FVo.

Ray, K.W. (2010). In pictures and in words: Teaching the qualities of good writing through illustration study. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Short, K. (2009). Critically reading the word and the world: Building intercultural understanding through literature. Bookbird: A Journal of International Children's Literature, 47(2), 1-10.

Literature Cited

Bell, D., & Colpoys, A. (2019). All the ways to be smart. Texas City, TX: Scribble US.

de Paola, T. (1997). The legend of the poinsettia. London, England: Puffin Books.

de Paola, T. (2001). The night of Las Posadas. London, England: Puffin Books.

Dunklee, A., & Forsythe, M. (2011). My name is Elizabeth! Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Kids Can Press.

Eliot, H., & Chau, A. (2018). Lunar new year. New York: Little Simon.

Hoyt-Goldsmith, D., & Migdale, L. (1999). Las Posadas. New York: Holiday House.

Jenner, C. (2008). Welcome to China. London, England: DK Publishing.

Lin, G. (2013). Bringing in the new year. New York: Knopf.

Marx, D. (2002). Chinese New Year. Danbury, CT: Children's Press.

Marx, T., & Senisi, E.B. (2010). Kindergarten day in China and the USA. Watertown, MA: Charlesbridge.

Moon, W. (2017). Let's explore Mexico. Minneapolis, MN: Lerner Publications.

Niemann, C. (2008). The pet dragon: A story about adventure, friendship, and Chinese characters. New York: Greenwillow Books.

Roman, C.P. (2013). If you were me and lived in…Mexico. Scotts Valley, CA: CreateSpace.

Wallace, A., & Elkerton, A. (2019). How to catch a dragon. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks.

Lacey Elisea has taught in early childhood classrooms for five years and is the kindergarten teacher at Creation School.

Jane Metzger has an early childhood/special education background and is a teaching assistant in kindergarten at Creation School.

Cassandra Sutherland has taught at Creation School for two years and is the physical education and art teacher in the elementary (K-3) school.

© 2021 by Lacey Elisea, Jane Metzger, and Cassandra Sutherland

WOW Stories, Volume IX, Issue 2 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work by Lacey Elisea, Jane Metzger, and Cassandra Sutherland at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/volume-ix-issue-2/4.

WOW stories: connections from the classroom

ISSN 2577-0551