The Hohokam People Project: Learning Through Windows and Mirrors in a Cross-Cultural Study

By Meghann Kjolsrud

I spent my childhood in South Dakota where I developed a love for nature and everything outdoors. I began working in education in 2001. In 2006, I took a break from my career to stay home with my four children. In addition to teaching, I have worked as a Religious Education Director, Family Program Coordinator, and a Preschool Director. In 2016, I obtained a M.Ed. with a specialization in early childhood with an aim to better understand early childhood development. I currently teach at Creation School.

Creation School is grounded on Christian principles and helping students develop a life-long love of learning. Two ways I accomplish Creation's goals are through Project Based Learning and a Global Literacy framework. Project Based Learning is used in many progressive schools today. However, the idea isn't new; the ancient teacher and philosopher Aristotle (383-322 BC) once said, "The things we have to learn before we do them, we learn by doing them" (as cited in S. Ramasubbu, 2015). A century ago, John Dewey, an educational reformer, expressed a similar viewpoint. He believed that students learn by doing and that teachers see themselves as facilitators, not instructors, who observe students' interests and abilities and provide them with what they need to problem solve, imagine, and create (Delisle, 1997).

I learned about global literature when I joined our Vail Global Literacy Community last fall. Through our readings and discussions, I learned types and foci of global literature, the concept of windows and mirrors (Bishop, 1990), the importance of cross-cultural studies, and the need to develop students' intercultural understandings. Kathy Short (2009) states, "Interculturalism is an attitude of mind, an orientation that pervades thinking and permeates the curriculum" (p. 2). Developing intercultural understandings became a goal for my classroom, curriculum, and students.

The cross-cultural study of the Ancestral Hohokam culture described in this vignette brought together Project Based Learning and global literature. The Hohokam were the Ancestral Indigenous people of the Sonoran Desert, where we live. Through this glimpse into our Hohokam People Project, I share how this study authentically impacted students' learning and our experiences. As Short (2009) also points out, "cross-cultural studies provide both a mirror and window for children as they look out on ways of viewing the world and reflect back on themselves in a new light" (p. 5).

Our Classroom

In 2020-2021 I taught a multiage 1st-3rd grade class of ten students, four girls and six boys, ranging in age from 6 - 9. Two students were first graders, four second graders, and four third. The students' ethnic origins and cultural backgrounds were primarily European American, but also Mexican, Brazilian, Korean, and Vietnamese. English was the primary language spoken in the students' homes.

Class Dynamic Challenges

A mixed age group and a small class size are ideal when individualizing education for each student and when using a Project Based Approach for learning. However, when it comes to competitive sports, a mixed age group and small class size can create challenges. Early in the year, the majority of third grade students loved playing gaga ball (similar to dodge ball) and soccer. However, because of the competitive nature of both games, social conflicts and emotional duress frequently arose. To have enough players for each team, almost all students had to participate. The third-grade students had an obvious advantage, and this caused a lot of frustration and discouragement among the younger students, especially those who had difficulty articulating why they were feeling discouraged and why they did not want to play. In an attempt to overcome this challenge, we held class meetings and group discussions. The students came up with their own fair guidelines for the games, but in the end, the first and second grade students lost interest and stopped playing. This brought about a temporary discord which was uncomfortable for all but perhaps necessary for the growth that was about to occur.

Figure 1. The class becomes interested in Garhett's waterway.

Finding Harmony

On a warm day in January, students stumbled upon a new kind of harmony. While spending time on the back desert playground, Garhett, a second grader, asked if he could turn on the water. He and Michael, another second-grader, began digging a waterway and discussing plans to build a dam. Within a short amount of time, the entire class was drawn into the project (see Figure 1). The students found shovels and began digging and moving dirt. When it was time to go inside, they eagerly asked to return the following day to continue what they had begun.

Figure 2. The first and longest Hohokam-inspired canal leading to the sand pit.

The whole class continued to choose the back playground each afternoon. There they talked, planned, and worked. Together they decided to construct a waterway that would eventually lead to the sand pit area on the far end of the playground (see Figure 2). As I watched them dig, their faces sweaty and determined, I was reminded of the Ancestral people of the Sonoran Desert, the Hohokam, and the seventy-five-foot canals they had built that stretched for over two-hundred miles. This was the start of our Hohokam People Project.

The Hohokam People Project

We began our study by reading This Place Is Dry by Vicki Cobb and Barbara Lavallee (1989) and The Hohokam: the Ancient Dwellers of the Arizona Desert (Doyle, 1991), where we learned about the desert and the expansive canals and irrigation systems the Hohokam people built. Students were very eager and engaged as we discovered the Hohokam's advanced engineering abilities. Immediately, they began to integrate this new "window" knowledge into their own work and play on the back playground. I saw them transition from digging a basic waterway, to building more sophisticated canals and irrigation systems for their "crops", and I listened in amazement as they began using the concepts and terminology from the literature we were reading. For example, when Garhett began collecting weeds, I asked him about his plan for the weeds he was holding. He responded, "I am planting crops. The canals are the water sources. We're going to bring the water to the crops that we're planting here (see Figure 3). Over there is another water source that goes to our house because every person needs water to survive."

Figure 3. Garhett builds canals that lead directly to the crops, integrating his new knowledge of Hohokam canals and the need for water.

Gaga Ball

When we read A Brief History of Hohokam Archaeology (Woodbury,1991), students made an exciting "mirror" connection. In this article, we learned about ancient ball courts and how they have been found in every village, adjacent to the plazas.

The students were fascinated with this discovery as it provided background on the game they played on our school's gaga ball-pit. Since it is still a mystery to archeologists as to how the game was played, I invited students to draw their depiction of the ball courts and the surrounding area and imagine, as if they were the archeologists, how they think the game was played.

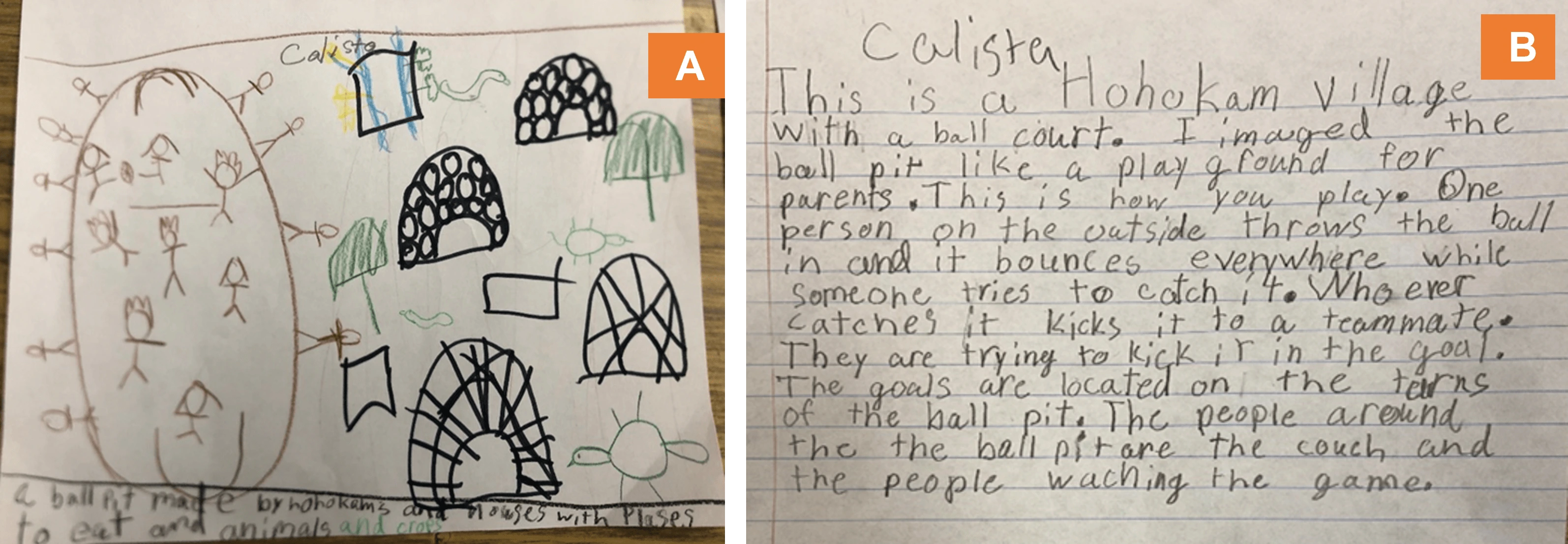

Figure 4 shows third grader Calista's drawing and writing. On her drawing (see Figure 4A) she wrote, "A ball pit made by Hohokams and houses with places to eat and animals and crops." In Figure 4B Calista described how she imagined the game was played: "This is a Hohokam village with a ball court. I imagined the ball pit like a playground for parents. This is how you play.

One person on the outside throws the ball in and it bounces everywhere while someone tries to catch it. Whoever catches it kicks it to a teammate. They are trying to kick it in the goal. The goals are located on the turns of the ball pit. The people around the ball pit are the coach and the people watching the game."

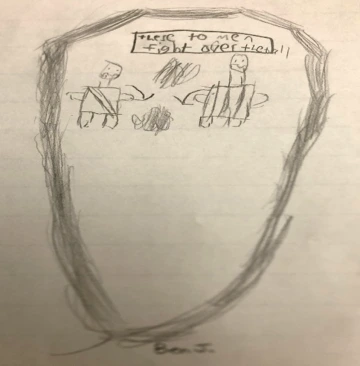

Ben's (3rd grade) drawing is in Figure 5. He drew an ancient ball court and wrote, "These two men fight over the ball." His personal experiences with soccer and gaga ball may have served as a mirror enabling him to make a special connection with the Hohokam ball game.

Figure 4. Calista’s (third grade) drawing of a gaga ball court (A) and description of how she

imagined the game being played (B).

Pottery

Another aspect of the Hohokam Culture that we studied was the pottery. Many students were familiar with pottery but learning about Hohokam pottery provided another window. Together we read Craft Arts of the Hohokam (Crown, 1991) and examined many traditional Hohokam pottery designs. Using air-dry clay, students then constructed their own pinch pots. When the pots were dry, they painted and designed their pots based on their individual interests. Students chose their favorite Hohokam design and practiced drawing it on paper before painting it on their pots. Figure 6 shows Liam painting his pinch pot.

Figure 5. Ben’s (third grade) drawing of an ancient ball court.

Many of the students painted their pot a reddish orange, as Liam did in Figure 6, similar to the Hohokam's red-on-buff pottery. However, some chose to paint their pots green, yellow, or different shades of blue. Several other students' finished pots are in Figure 7.

Casa Grande

We also learned about Casa Grande, located in the Casa Grande National Ruins Monument about 90 miles north of Vail. Casa Grande is the tallest and most massive Hohokam building known, standing 35 feet tall (https://www.nps.gov/cagr/learn/photosmultimedia/multimedia.htm). We learned it was built with almost 3,000 tons of caliche (https://www.nps.gov/cagr/learn/kidsyouth/the-casa-grande.htm). Caliche is a shallow layer of soil consisting of different particles that have been cemented together (https://aces.nmsu.edu/pubs/_a/A151/welcome.html). To get caliche, the Hohokam had to dig in the ground for it.

When we were back outside, students began integrating their new learning. Calista decided to construct a house based on information she learned about the Casa Grande (see Figure 8).

Figure 6. Liam (third grade) carefully adds his Hohokam-inspired design to his pinch pot.

Other students talked about caliche and decided to dig for it, initiating a shared class love, excitement, and fascination with it. Students dug enormous holes (see Figure 9-A) and collected the mud and caliche (see Figure 9-B). On their own, they decided to make caliche pots and laid them on large rocks in designated areas to bake in the sun (see Figure 9-C). Some students even started their own Caliche Pot Making Factory.

The end of the school year arrived long before the students and I were ready. There was no time to paint the caliche pots, no time for more reading and exploring, no time for final reflections in writing and art. Mrs. Hook (our school administrator) asked us to fill in the holes and canals students had dug and return the desert area to its original state in preparation for the next school year and to prevent a huge muddy mess when the monsoon rains hit over the summer. The students were devastated. To cheer them up, Mrs. Hook gave them several jars of "treasure" (old trinkets) to bury and be discovered by next year's students. I have come to realize that on that day, we buried another treasure, a rare gem in the desert, our Hohokam People Project; and that our memory of it would be patiently waiting to be rediscovered in our minds.

Figure 7. Other students’ pinch pots with Hohokam designs.

Closing Thoughts

After reflecting on our Hohokam Project, it is evident how it provided windows and mirrors for students. Through windows, such as learning how to get water to crops and build homes in the desert and digging for caliche to build homes and create pots, students developed a respect and appreciation of Hohokam culture; Hohokam ways of living, being, and thinking; and Hohokam creativeness and resourcefulness. In addition, these windows helped my students navigate and overcome the social-emotional challenges in their everyday lives.

As we read, dug, and made new discoveries, we also spent time reflecting and discussing "How and why do you think the Hohokam people were able to create such complex canal systems?" I used this question as a window to generate discussion on collaboration and teamwork and highlight another learning from the Hohokam that was occurring as they worked together on the canals and with the caliche.

Figure 8. Calista (3rd grade) adds an entrance to the house she begins to construct with a similar design to the Casa Grande.

Our study of the Hohokam's amazing accomplishments helped students learn not only about Hohokam people and culture, but that respect for others and their perspectives, effective communication, and collaboration are necessary in communities to accomplish any big project or task.

As a mirror, the need for shade was very real for myself and students, as it must have been for the Hohokam. Each day our skin would begin to feel hot and sore from the direct sunlight beating down on us, but as we dug, we were transported back in time. Because we share the same desert as the people we were studying, students identified with what it must have been like for the Hohokam. Like the Hohokam, we experienced a real need for shade, shelter, water, and tools. This mirror showed us one of many common human experiences (i.e., love of family, need for food and shelter) we shared with the Hohokam across time and from these, a genuine admiration and appreciation for the Hohokam people and their way of life.

We were not ready for this project to end, feeling that we had only begun to discover and explore the Hohokam People. Through this journey and our study, we came to appreciate the Hohokam People. They achieved high-level thinking and complex social abilities to build elaborate irrigation canals that watered crops and fed thousands of people over a thousand years ago and without the use of modern tools.

Students also came to know themselves and grow in who they were individually and as members of a community that works together and respects each other's perspectives and talents. Although our project has ended, a new beginning has begun to emerge, one filled with feelings of deep respect and admiration for our fellow desert dwellers, the Hohokam People of the Sonoran Desert.

References

Bishop, R.S. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives, 6 (3), ix-xi.

Cobb, V., & Lavallee, B. (1989). This place is dry: Arizona's Sonoran desert. London: Walker.

Crown, P.L. (1991). Craft arts of the Hohokam. In D.G. Noble (Ed.), The Hohokam: The ancient people of the desert (pp. 39-59). Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press.

Delisle, R. (1997). How to use problem-based learning in the classroom. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Doyle, D.E. (1991). The Hohokam: The ancient dwellers of the Arizona desert. In D.G. Noble (Ed.), The Hohokam: The ancient people of the desert (pp. 3-15). Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press.

Ramasubbu, S. (2015, April 1). The art of learning by doing. Huffpost. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/the-art-of-learning-by-do_b_6580006.

Short, K. (2009). Critically reading the word and the world: Building intercultural understanding through literature. Bookbird: A Journal of International Children's Literature, 47(2), 1-10.

Woodbury, R.B. (1991). A brief history of Hohokam archaeology. In D.G. Noble (Ed.), The Hohokam: The ancient people of the desert (pp. 27-46). Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press.

Meghann Kjolsrud has worked in elementary/early childhood education since 2001 and currently teaches Grades 1-3 at Creation School.

© 2021 by Meghann Kjolsrud

WOW Stories, Volume IX, Issue 2 by Worlds of Words is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Based on a work by Meghann Kjolsrud at https://wowlit.org/on-line-publications/stories/volume-ix-issue-2/5.

WOW stories: connections from the classroom

ISSN 2577-0551